On View: December 1

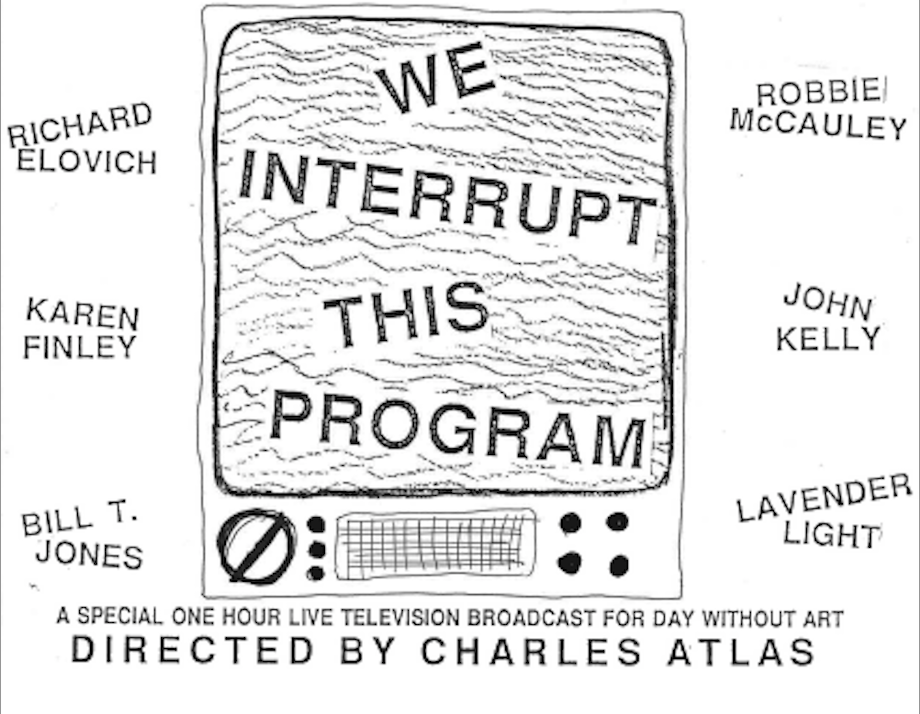

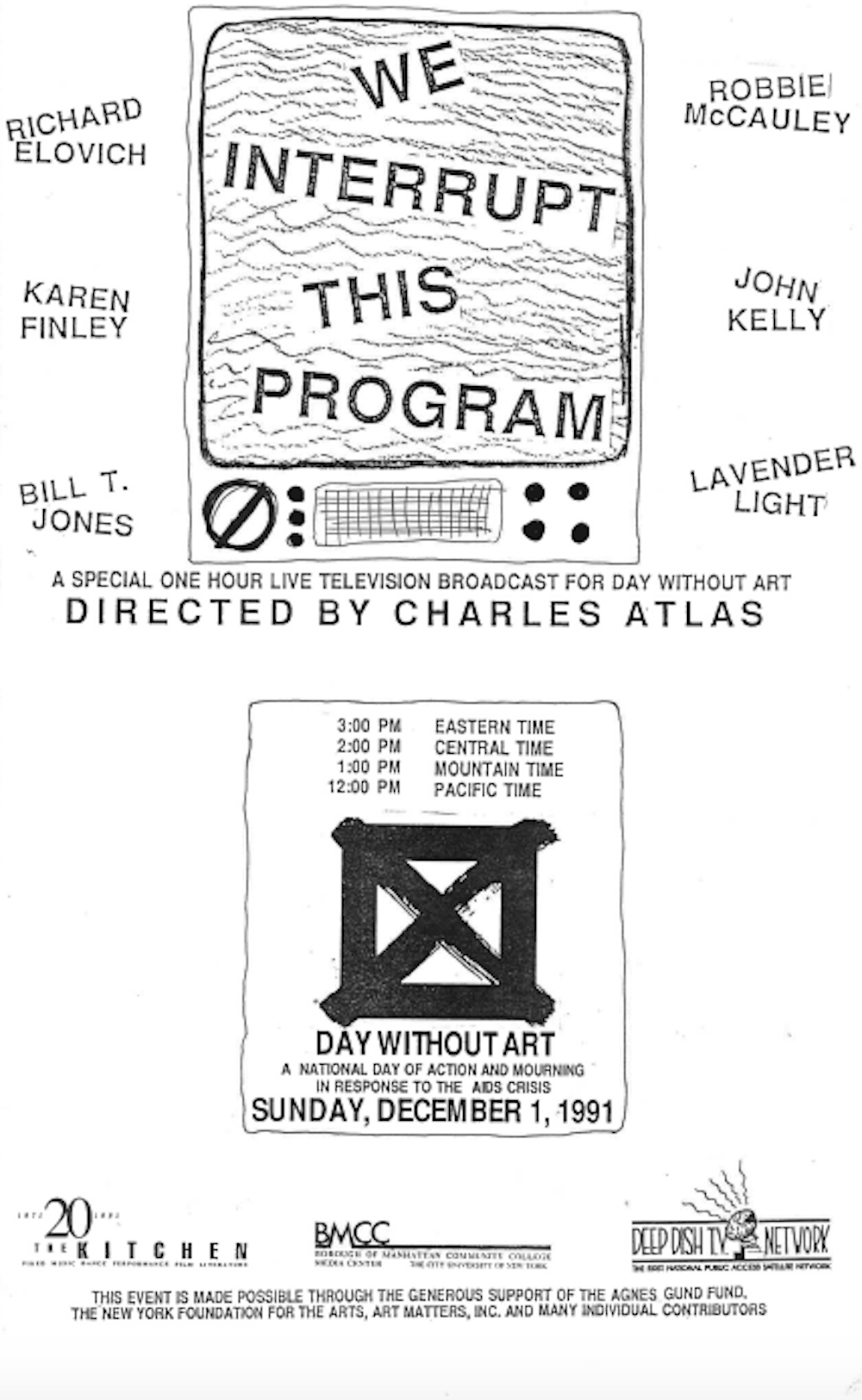

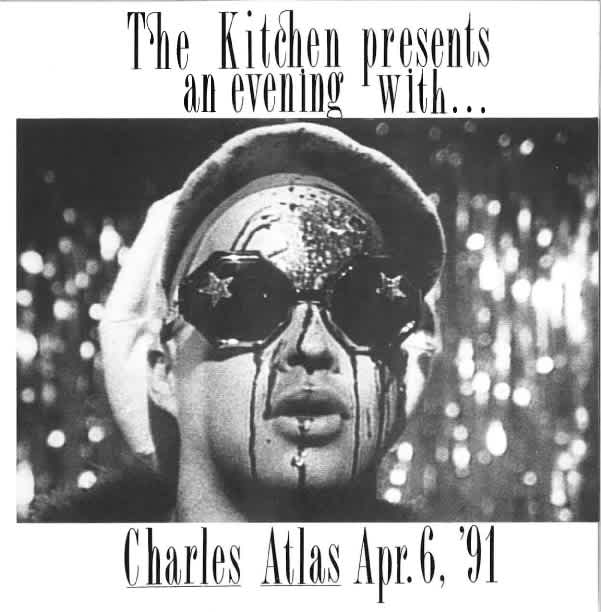

This Video Viewing Room features a recording of the live television broadcast We Interrupt This Program (1991), presented by The Kitchen in association with Visual AIDS for Day Without Art 1991. The broadcast was directed by Charles Atlas and included performances by DANCENOISE, Richard Elovich, Karen Finley, Bill T. Jones and Estella Jones, John Kelly, Lavender Light, and Robbie McCauley. Additionally included on this page are ephemera from The Kitchen’s archive and a video conversation between Atlas, scholar Roderick Ferguson, art historian and former Visual AIDS Program Director Alex Fialho, and McCauley, recorded in November 2020. The written transcript of that conversation follows, with minor edits made for style and clarity.

Produced nearly thirty years ago, We Interrupt This Program is an interdisciplinary endeavor in which several of The Kitchen's founding commitments and programmatic specialities converge: this live television event engaged with urgent social issues, brought together members of The Kitchen's artistic community for a collaborative project, and utilized forms of video and broadcast technology in unique ways. Drawing from the ethos of the original production, which wove together contributions from artists whose work addressed the AIDS crisis in diverse ways, The Kitchen convened a conversation in November 2020 among individuals who participated in We Interrupt This Program and those who animate the legacy of this broadcast event through their current teaching and programming.

Alex Fialho [AF]: I’m going to read a paragraph that was in the initial proposal for the program. It reads, “The impact of AIDS on the arts and the fabric of our culture is immeasurable. The presence of the disease in the artist’s personal lives has generated a moving and inspiring body of artistic work concerned with AIDS and HIV infection. Often hard hitting and personal, this work recognizes the tremendous loss of talent, which the crisis has brought on, as well as encourages additional measures to help those who are living with AIDS. The purpose of this program is to create a platform through which these performances and video artworks can be brought together with educational materials in a live television format.” I think that sets out the stakes of the project really well.

It was a live television broadcast directed, of course, by Charles Atlas, featuring Robbie McCauley, John Kelly, Bill T. Jones and his mother Estella Jones, Karen Finley, DANCENOISE, Richard Elovich, and Lavender Light. It had educational materials and video clips, including Kissing Doesn’t Kill by Gran Fury, Diana’s Hair Ego by Ellen Spiro, and many more. There were downlinks from Montana, the Wexner Center in Ohio, the Contemporary Art Museum in Houston. So it was a very jam-packed hour of programming around AIDS and its really urgent and pressing concerns in 1991. And it was produced by Robin Schanzenbach, Mary Ellen Strom, and Barbara Tsumagari.

DANCENOISE in their introduction as hosts of the program said [2:44 in the recording of We Interrupt This Program], “Our December 1st pledge: we pledge to remember those that have died, to fight for effective treatment for those infected, and to work every day to stop the spread of the disease with the only tool that we have. Get ready to get moved to action.”

So given all of that information and thinking about the DANCENOISE December 1st pledge, Charles and Robbie, I’m interested, can you take us back to December 1, 1991? You were both there working together to make the live broadcast happen. What’s most memorable and noteworthy about the process of creating We Interrupt This Program today?

Robbie McCauley [RM]: My memory of that time was one, basically, of surprise. Because I myself was not as active as I felt like I should have been around the whole crisis, and so when I was asked to participate, I wondered, “what can I say?”

And realizing the friends who, one by one, I heard had the disease. One by one were dying. I realized that my work had to do with the personal story and the personal responses, as well as how the personal connects to larger things. And so I felt, OK, this is the place for me.

I also had been working with improvisation—what I began to call the aesthetics of improvisation, coming out of jazz. And so, even though I’d found some language that I was repeating, I started off just kind of talking from my feelings, from my guts. And then shaped that into that, I think it was, what, ten or fifteen minutes, that each artist had. And so I cobbled that together in the way that one might cobble a jazz piece.

Charles Atlas [CA]: I think actually each artist had five minutes.

RM: Oh maybe it was that short. I remember sculpting a lot.

CA: I try to get back to the zeitgeist of the time. I had a personal relationship—my partner is an HIV/AIDS patient, who is still alive, who had HIV from 1982. He didn’t really go into the hospital until ’95 when he really got sick. But he was HIV positive on medication in ’91.

And I knew a lot of people who had passed away. And in my daily life, I kept on running into people who were not aware of the fact that gay men should practice safe sex. Everyone should practice safe sex. So I felt that my job was really to educate people and make them aware of these kinds of things.

I put in images that were scary, and I got a response from the living-with-AIDS community that they didn’t appreciate that, that they weren’t all sick people, that it should have been emphasized. But I saw people dying. And so I felt it was important to scare people a little bit.

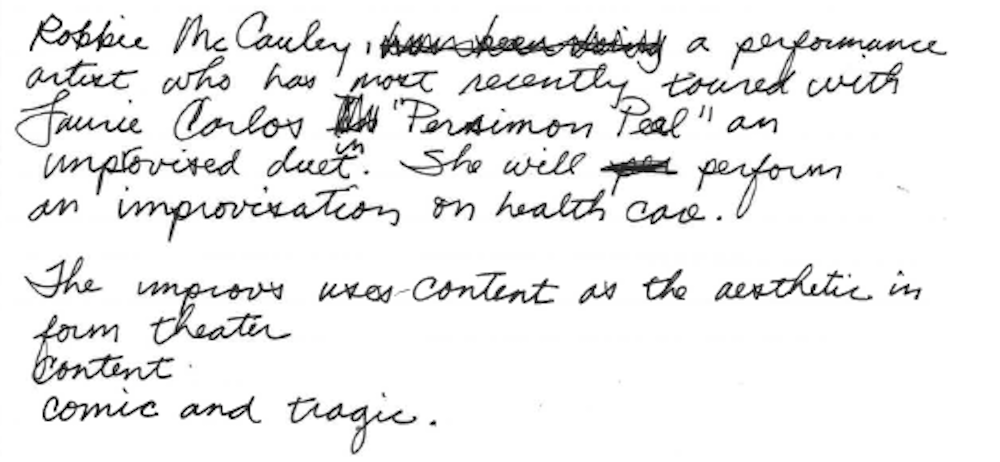

AF: One of the revelations in The Kitchen’s archival material is a note that someone had written about your performance, Robbie, that it was an improvisation. And [your performance] is titled “An Improvisation with Two Friends.” But there’s so much power in so many of the lines, and the lines are so well aligned with what you’re saying. Your movement feels very rehearsed. Can you talk a little bit more about your improv practice and if the movement was improv, if the text was improv? What were you thinking about on the fly in that moment?

RM: My theater training was out of a process with Kristin Linklater. She was an incredible innovator in terms of voice for actors, which she connected to the body. And so by that time, I had embodied that practice of finding my words connected to the body and the feelings.

I did For Colored Girls [Ntozake Shange, For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When the Rainbow Is Enuf (1976)], and that process was a part of that with other actors coming from different disciplines, but using the body and the voice at the same time.

The improvisation was also part of my theater practice. And I was working with, as I said, a jazz band, and I would translate the jazz process to the acting process. How one can take a moment and stretch it out verbally to see where it goes. And every once in a while, take a bit of text out of something and weave that in. So I love playing like that with text, body, and sound.

AF: I have a follow up question around that embodiment. There’s this moment in your performance where you say, “I’ll never tell” [24:48 in the recording of We Interrupt This Program]. Which was related to the idea of disclosure [of HIV status]. And then you kind of turn away from the camera. I’m curious to hear you reflect on how performance in the body and these ideas of memory and loss were a way for you to think about AIDS, remembrance, and response to the AIDS crisis at that time.

RM: Well, as I said earlier, it was overwhelming from a personal standpoint, and a bigger standpoint, because there was nothing governmental being done about it.

But I was also inspired by the activists who were out there. You mentioned Richard Elovich, whose work I remember being on the ground.

You know, I can’t help think now about the [COVID-19] pandemic in a similar way. That you’re going about your business, and all of a sudden there’s something in the air that is threatening your friends, your family.

I was devastated by AIDS. The small five minutes was something that I felt I could move with, I could do something with.

AF: Professor Ferguson, Rod, can you contextualize your ideas of multidimensionality? The full course title [for your course at Yale University] is “We Interrupt This Program: the Multidimensional Histories of Queer and Trans Politics.” Can you talk a little bit about why this program is the namesake for your class, what the one dimensionality of AIDS representation might be considered, and how this is an example of multidimensionality?

Roderick Ferguson [RF]: One of the things that inspired me about the program when I first viewed it was the deliberate presence of women and people of color in it. I think that that was part of your vision, Charlie.

CA: It was just the natural course of things. It wasn’t really an intentional thing.

RF: Well, this is the interesting thing—that in that time, what was for you the natural course of things was also a detour for much of the conversation around HIV/AIDS, which oftentimes was pitched as about sexuality. All these other things having to do with race, having to do with gender, having to do with class—they were not really talked about as part of what was going on. And so I saw the program in many ways as, intentionally or not, a kind of rebuttal to that single-issue focus around HIV/AIDS. That HIV/AIDS, yes, it is about sexuality. But it also has to do with race, class, gender.

And the wonderful thing about the program was that you saw that argument embodied in the various artists. There’s Robbie’s performance, there’s Lavender Light, there’s Bill T. Jones and his mother Estella Jones. And so for me, it was the perfect example of a kind of multidimensional artistic and also political take on the HIV/AIDS crisis and HIV/AIDS struggles.

CA: I think the idea for the program was originated by Mary Ellen Strom and Bobbi Tsumagari. And I’m sure that they are the ones who at least suggested the performers. I think they picked a lot of them. DANCENOISE and Karen Finley were my friends, so I probably got them in. But I think the rest of the people I didn’t know that well. And John Kelly I’d worked with before. They [Mary Ellen and Bobbi] were responsible for the overall, and I was responsible for the structure of the program and directing the individual things. I didn’t really direct the performers. They all directed themselves, basically. I directed the cameras.

RF: Still one of the amazing things about it is that it really is a kind of archival document of why HIV/AIDS and the politics around it have to be understood as about sexuality’s intersection with race and gender and class. So it is pretty unique and singular in that way.

RM: It’s also about art. Because, you know, so many artists are of the community. And as I said, we all knew each other.

AF: Here are a few lines from Professor Ferguson’s syllabus: “The course extends the show’s theory of art and politics as conjoined social practices. For the show, this was necessarily the case in a moment in which neither government nor industry could be relied on to resolve the devastations of HIV/AIDS, the ravages of poverty, or the consequences of heteropatriarchy, transphobia, and racism. Indeed, the show demonstrated how those issues had to sit within the same critical and artistic space precisely because of the fact that they overlapped in the social worlds.” Can you talk a little bit about the program as a pedagogical tool? How have you used it in the classroom, and how have students responded to it?

RF: I begin with DANCENOISE and their alternative Pledge of Allegiance, and ask students to consider the ways in which that alternative Pledge of Allegiance is very different from the US Pledge of Allegiance. Because I also want to think about how the pilot program is a critique of US nationalism, especially at that moment when the government was turning its back on people, and people were dying.

And so then we go to Lavender Light’s performance of “I Will Remember” [3:41 in the recording of We Interrupt This Program]. And I do a bit of contextualization for the students in that I tell them that “I Will Remember” is a song that was first performed by the gospel group, the Winans, and in particular Ron Winans, and also that it refers to a line within one of the Negro spirituals “Dear Lord, Remember Me.” And so through that performance, you have this LGBTQ choir invoking the histories of slavery, and also invoking civil rights, but also critiquing the Black church’s participation in homophobic discourse and then re-articulating that history so that this song will then speak to people who are on the margins of sexuality and gender as well.

So that the song does a lot of work in that it revises Black performance practices, particularly from the church. It also invokes the [questions of] how do you get through slavery and also the history of the civil rights movement and the place of sacred songs in the civil rights movement. And all of that comes to bear in the moment of “what do we do about HIV/AIDS and its effect on various communities?”

AF: Charles, I want to ask you a little bit about the medium of TV, because this was a live program that was being seen all over the country on television.

CA: It was a cable Manhattan neighborhood network. Deep Dish Network. It wasn’t a major feature on broadcast.

AF: Did the idea of working on a television program change how you were thinking about it?

CA: I had been a TV addict and making works for TV since the ’80s. And so I had done one live thing before. But the live thing is a real challenge, and I am a perfectionist. I hate live television really, because you don’t get everything exactly right. In fact, I think the version of the program that you all see is slightly edited from what the original program was. I mean, not a lot, but I think some things were tightened, maybe.

AF: As a follow up to that, one of the things that Kyle Croft, Visual AIDS Program Director has mentioned is that you have a well-known video, Son of Sam and Delilah (1991), which also has John Kelly and DANCENOISE in it, from that same moment. That’s a very different take and a very different context. Could you talk about the range of ways that you were thinking about responding to AIDS in that moment?

CA: I felt that my program about AIDS, Son of Sam and Delilah—people didn’t get it. It was banned on TV. It was supposed to be broadcast, but then PBS withdrew it. It was a big scandal in the Times, and I was on CNN, saying it’s homophobic of PBS. I was blacklisted from PBS for about 10 years. So there was pushback.

AF: What does it mean for you, Robbie and Charles, to return to this program now, reflecting on it thirty years later. How does it resonate in the present for you?

CA: Well, for me, watching it again, I see the similarities between AIDS and COVID, but it really seems like a whole different era in our consciousness. And all the things that have come out into the open more in those thirty years were really submerged at this time.

Transphobia wasn’t a thing that people were even talking about at that time. It still existed, but it wasn’t a New York Times story of the week.

It just took me back to that time, really. We were naive then. That this was really going to be solved by someone.

RM: It has been said about our culture—if there’s such a thing as an American culture—that we resist looking at [death] and talking about how hard it is for us to face death. And I think that has changed. I think that continues to change. Again, I can’t dismiss it from COVID—that it’s in our faces. With AIDS, it was in our faces, but not so largely.

So there’s been a cultural change. And I also think that citing memory is important—that we keep the past with us as best we can. And artistically, add beauty to memory.

RM: Speaking of the class, I get really excited to see the students excited and inspired by works like We Interrupt This Program. Because a lot of what the students say is “how come we don’t already know about this?” And “why aren’t we being taught this?” And just today a student said that “these are texts that I need.” So that gives me a lot of encouragement and hope.

AF: “We Interrupt This Program” is the title of the class and the title of the project—how can we think about interruption and intervention as a sort of analytic? What were you interrupting, Charles, with your project? What does your class interrupt, Rod? What was your performance interrupting, Robbie?

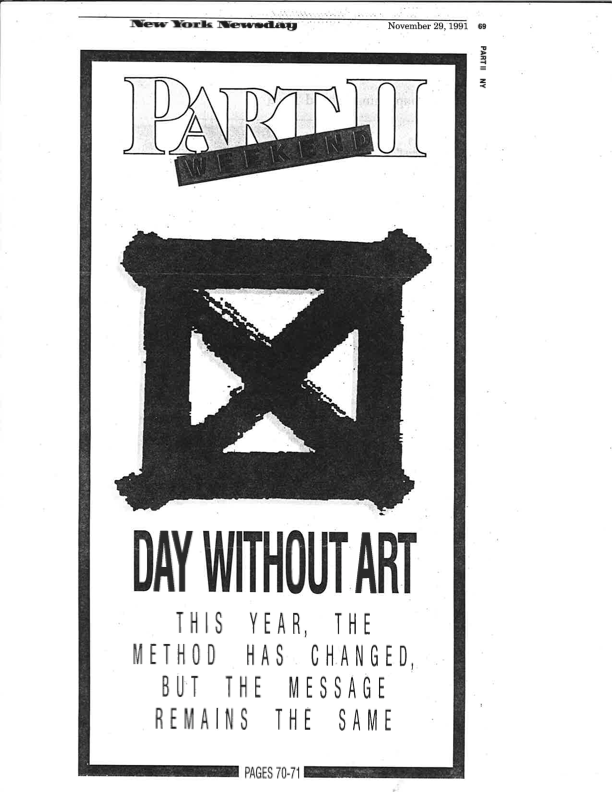

CA: Well Day Without Art is interrupting the production of art. So it’s a little bit paradoxical that we were creating art on the “day without art” to interrupt.

But it was just a time to take a moment. I know there was discussion among artists and friends of mine about—are you really going to stop working today? And is making art not what we do to resist all that? So it was just bringing that subject up for conversation.

RM: I thought making art was a way of interrupting by concentrating on the subject matter. And so I thought the interruption was more of a focus rather than a real interruption.

CA: I think mainly the direction was to get museums to close. And I don’t know how many of them did. That was the art that we were taking away from people. This was the art that we were giving them.

AF: There’s a powerful history of Day Without Art in that sense. In its earliest years—1989 was when it was founded into the 1990s—museums would either close or shroud artworks in black cloth to represent the absence. Very famously, the Guggenheim put a black shroud over its facade [in 1991]. In the program [We Interrupt This Program] itself, you see in Montana, they’re covering a statue in Helena, in front of the Capitol there. And in the early years, between 600 and 800 institutions would contribute and be involved in some way.

CA: I think the very first few made an impact. Less so as it went on I think.

AF: Yes, it has wavered. There have been waves of interest in the program, but also silences and waves of AIDS activism and attention.

But even this idea of showing or not is involved in the name of Day Without Art. At the ten year mark [in 1998], Visual AIDS put parentheses around “out” [Day With(out) Art]. For the first ten years, it was Day Without Art. And the idea was that sometimes there would be absences or closures. But as you were saying Charles, there’s the question of making this program on Day Without Art. So the parentheses makes for the possibility of a day with art, too.

In your performance Robbie, you say really emphatically, “on this Day Without Art, I say more art.” [A video of this conversation] is going to be launched on December 1st for Day Without Art 2020. So I’ll ask you all, for this Day Without Art, nearly 30 years later, what would you wish for more of?

RM: I think someone should propose December 1st as a holiday.

CA: I wish for more Democrats in positions of power.

RF: I wish for more of a world that will accommodate people on the margins.

AF: I wish for more connections and conversations with artists and scholars like the three of you.

BIOS

Charles Atlas has been a pioneering figure in film and video for over four decades, forging new territory in a far-reaching range of genres, stylistic approaches, and techniques. Atlas has fostered collaborative relationships throughout his production, working intimately with such artists and performers as Antony and the Johnsons, Leigh Bowery, Michael Clark, Douglas Dunn, Marina Abramović, Yvonne Rainer, Mika Tajima/New Humans, and most notably Merce Cunningham, for whom he served as in-house videographer from the early 1970s through 1983.

Roderick Ferguson is professor of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Yale University. He is the author of One-Dimensional Queer (Polity, 2019), We Demand: The University and Student Protests (University of California, 2017), The Reorder of Things: The University and Its Pedagogies of Minority Difference (University of Minnesota, 2012), and Aberrations in Black: Toward a Queer of Color Critique (University of Minnesota, 2004). He is the co-editor with Grace Hong of the anthology Strange Affinities: The Gender and Sexual Politics of Comparative Racialization (Duke University, 2011). He is also co-editor with Erica Edwards and Jeffrey Ogbar of Keywords of African American Studies (NYU, 2018). He is currently working on two monographs—The Arts of Black Studies and The Bookshop of Black Queer Diaspora. Ferguson’s teaching interests include the politics of culture, women of color feminism, the study of race, critical university studies, queer social movements, and social theory. His course “We Interrupt this Program: The Multidimensional Histories of Queer and Trans Politics”—taught at Yale in Fall 2019 and Fall 2020—takes inspiration from the 1991 broadcast We Interrupt This Program.

Alex Fialho is a graduate student in Yale University’s Combined Ph.D. program in the History of Art and African American Studies. As an art historian and curator, his research and writing focus on contemporary art, activism, Black studies, queer theory, and HIV/AIDS scholarship. Previously, Fialho worked for five years as Programs Director of the New York-based arts non-profit Visual AIDS, facilitating projects around the history and immediacy of the ongoing AIDS crisis, while intervening against the widespread whitewashing of HIV/AIDS cultural narratives. As an Oral Historian for the Smithsonian Archives of American Art’s Visual Arts and the AIDS Epidemic: An Oral History Project, Fialho conducted extensive oral histories with fifteen cultural producers including Gregg Bordowitz, Douglas Crimp, Nan Goldin, Lyle Ashton Harris, and Julie Tolentino. Fialho holds a B.A. in Art History with Honors and Distinction from Stanford University, where, with Melissa Levin, he recently co-curated the exhibition Michael Richards: Winged and co-organized the academic symposium “Flight, Diaspora, Identity, and Afterlife: A Symposium on the Art of Michael Richards.”

Robbie McCauley is a recent recipient of the IRNE (Independent Reviewers of New England) Award for Solo Performance and was selected as a 2012 United States Artists Ford Foundation Fellow. McCauley has been an active presence in the American avant-garde theatre for several decades. She received an OBIE Award and a Bessie Award for Outstanding Achievement in Performance for her play, Sally’s Rape. Her work is widely anthologized including in the texts Extreme Exposure, Moon Marked and Touched by Sun, and Performance and Cultural Politics, edited respectively by Jo Bonney, Sydne Mahone, and Elin Diamond. One of the early cast members of Ntozake Shange’s For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When the Rainbow is Enuf (1976) on Broadway, McCauley went on to write and perform regularly in cities across the country and abroad. McCauley is Professor Emerita of Emerson College Department of Performing Arts and the 2014 Monan Professor in Theatre Arts at Boston College.

Day With(out) Art is an international day of action and mourning in response to the AIDS crisis that takes place annually on December 1. Visual AIDS organized the first Day Without Art in 1989 in response to the worsening AIDS crisis and coinciding with the World Health Organization’s second annual World AIDS Day on December 1. A committee of art workers (curators, writers, and art professionals) sent out a call for “mourning and action in response to the AIDS crisis” that would celebrate the lives and achievements of lost colleagues and friends; encourage caring for all people with AIDS; and educate diverse publics about HIV infection. In years since the first Day Without Art in 1989, various arts organizations, museums, and galleries have participated through actions such as shrouding artworks and replacing them with information about HIV and safer sex, locking their doors or dimming their lights, and producing exhibitions, programs, readings, memorials, rituals, and performances. In 1998, for its 10th iteration, Day Without Art became Day With(out) Art. Visual AIDS added the parentheses to highlight the ongoing inclusion of art projects focused on the AIDS pandemic, and to encourage programming of artists living with HIV. To learn more about Day With(out) Art, visit the Visual AIDS website.

Production and Performance Credits

We Interrupt this Program was presented by The Kitchen in association with Visual AIDS for Day Without Art on December 1, 1991. It was co-produced by The Kitchen and The Media Center, BMCC/CUNY and broadcasted by Deep Dish TV.

Directed by Charles Atlas

Produced by Robin Schanzenbach, Mary Ellen Strom, and Barbara Tsumagari

Hosts: DANCENOISE (Anne Iobst and Lucy Sexton)

Lavender Light, The Black and People of All Colors Lesbian and Gay Choir, “Please Touch Somebody” and “I Will Remember” Musical Director: Tony Teal Choir Members: Dionne Freeney, Roger Carroway, Calvin Merritt, Terry Maroney, Jacqueliyn Holland, James Williams, Barbara Levy, Susan McConnaughy, Kenneth J. Lockwood, Marilyn Cole, Dwayne Henderson, Daniel Sager, Thomas Bagby, Michael Dinonissiou, Karen Gamble, David Macedon, Denise Fulton, Ellie Rosenberg, Jacqueline Jones, Jennifer Koontz, Ledina Ladson, Martina Downey, Tanya Henderson, David Johnson, Jordan Thaler, Maria Elena Grant

Richard Elovich, an excerpt from “Someone Else From Queens is Queer”

Robbie McCauley, “An Improvisation on Two Friends”

John Kelly and Company, an excerpt from “Maybe It’s Cold Outside”

Bill T. Jones with Estella Jones, “A Prayer”

Karen Finley, “In Memory Of”

Administrative Coordinator: Michele Rosenshein

Facilities Supervisor: Paul Weber

Publicity: Eric Latzky

Production Associate: Jeanne Finnerty

Deep Dish TV

Executive Director: Steve Pierce Operations Manager: Dolores Perez Programming Director: Martha Wallner

The recording of We Interrupt This Program was originally digitized and made available on the Internet Archive by XFR Collective.