On View: April 10

On Screen

This Video Viewing Room features a video of Lex Brown’s performance Foccaciatown:Reloaded (2019) along with related images and an accompanying text written by the artist.

Focacciatown takes place in a future in which the United States is no longer a country but a collection of monarchical nation-states organized by food and beverage brands. At this fast-casual-bakery-chain-cum-military-base, nestled in the grain fields of midwest North America, the days of steel and glass architecture have long since passed, and people have reverted back to concrete fortresses, dungeons, and medieval structures of social power. Yet telecommunications and advanced strategies for consumer marketing still exist. This is a regressive future of tyranny and brand omnipotence—a Mediaocracy. Only in this time would a Black man be shot for carrying a bag of potato chips.

Siting Focacciatown in the “future” and framing it as a fairy tale is its biggest joke, as we recognize how much its world is a distillation of today. We live in a world in which the advancements of marketing language far exceed our general skills for interpersonal communication; basic existence is criminalized for many; only a few food conglomerates control the global supply chain; and technology has drastically altered intergenerational relationships.

In the spring of 2016, when I wrote the three-minute monologue that would eventually become the hour-long operetta Focacciatown (2017), I was grappling with the then-novel mainstream news coverage of police brutality towards Black and Brown Americans. It had been two years since Ferguson, and the news cycle was still reporting regularly about these events. I had also recently watched the documentary Somm on Netflix and was impressed to learn how much geographical information sommeliers can identify by merely tasting a wine—a sensory skill that we might all have if our food was still connected to the heritage of the land.

In the monologue, Arial Black, an affluent woman named after a font type, spoke with a friend at brunch about the events of her week: a visit to a high-tech incubator carrying her baby to full term, and an incident at her home in which her husband called the neighborhood security on an unknown man for bringing chips to their house party instead of wine. His bag of Lays reveals that he’s from the terroir of what was formerly New Jersey, and carries with it heavy political implications.

Several months later, in the fall of 2016, I was processing what it meant to have a president with a fifteen-season-long track record in producing reality TV. I remember going to sleep on election night, staring at the ceiling, and wondering how I could possibly make a relevant artwork as I was now suddenly an unpaid actor in what will [unfortunately] be remembered as one of the best media productions of the 21st century.

For the four previous years, my performances had taken a more direct conversational/spoken poetry approach with the audience—much closer to a musician talking to the audience between sets. This candid mode no longer felt fitting; I felt that the concept of my performance needed to match, as closely as possible, the sophisticated, and nonsensical storytelling playing out in our reality. Of course all presidents are fiction, and the United States is a grand fiction, but 2016 marked an entrance into something more meta than ever before.

How do you write something sincere when real life is a farce? This question is what yielded Focacciatown’s soapy family relations, and the revelatory moment that Brioche’s parents baked her into a loaf of bread to save her from incineration. The audience is often caught not knowing whether or not to laugh. What was more important than this lifelike tension, though, was the positive resolution to the narrative, in which the sardonic Brioche reanimates her slain brother Andre with love and belief. He returns to life, limb-by-limb, in a moment of triumph and exuberance.

Focacciatown:Reloaded (2019) reframed and distorted the history of the original story. In this performance, two time travelers—a narrator and her A.I. Heuston—are brought back to watch Focacciatown in order to fix a tear in their navigation system. It turns out that the story did not resolve as positively as we thought it did in 2017, due to the manipulations of newscaster Melanie who has been coerced by a group called the Crusade to cast the victim of the shooting (Brioche’s brother Andre) as the perpetrator of the crime. Her broadcasts have “overwritten” the historical file in the travelers’ computers and they are unable to move forward until the plot arc has been restored to its original state.

Rather than creating a sequel that begins where the first chapter ended, the sequel condenses the entire hour-long plot line of the 2017 performance into twenty minutes, and spends the final 20 minutes rewinding, dramatically altering, and replaying a five-minute sequence of the original story. Focacciatown:Reloaded is as much about plot as it is about the live act of stretching and condensing digital time.

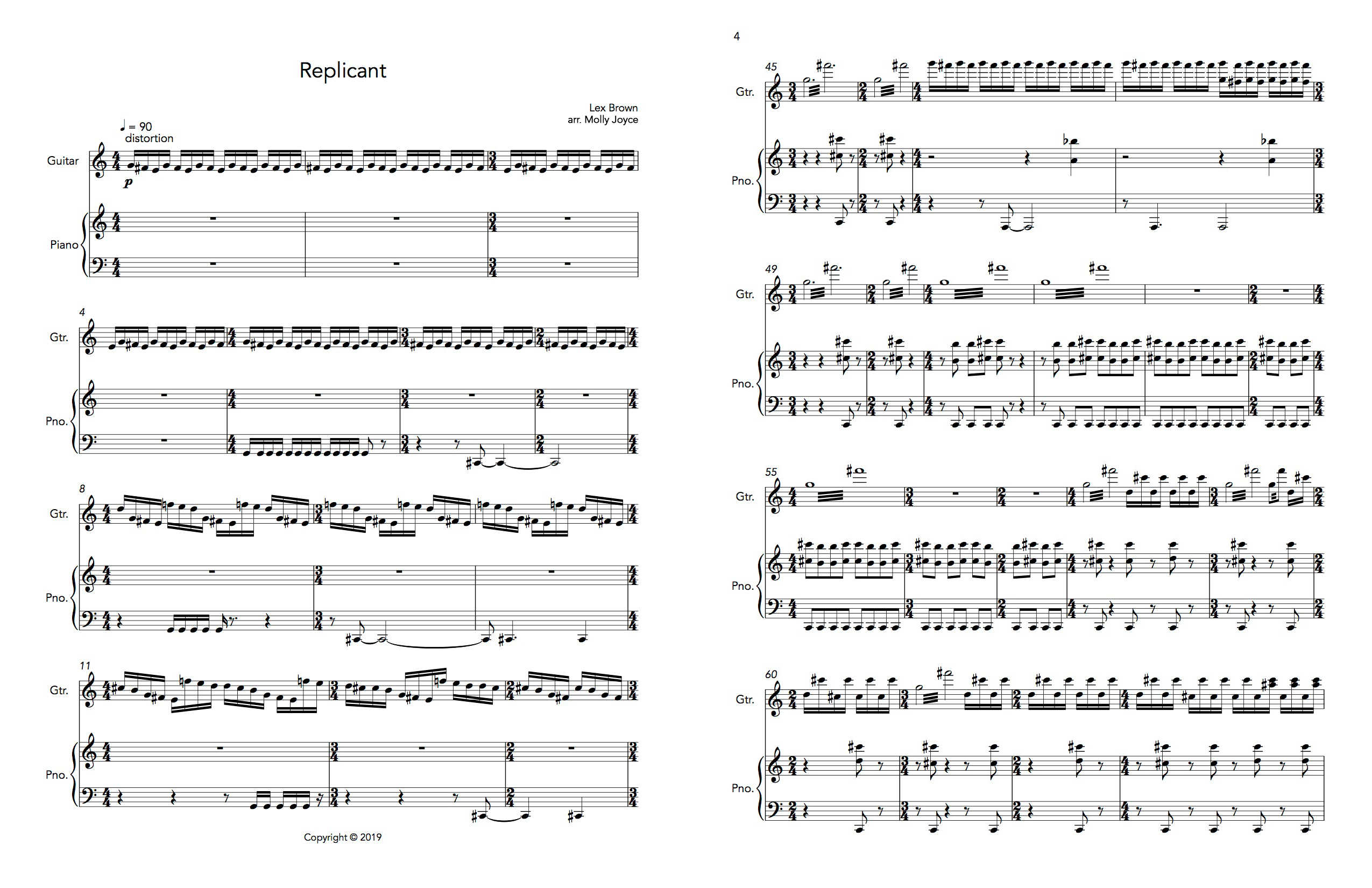

My work is sometimes described as “absurd,” when it would be more accurate to call it “the minutes” of a meeting that contains so much information that an attempt to summarize only seems laughable or illogical. I call the world of my work the Mediaverse—as in a universe of media, but also an extended verse of prose composed through different artistic media including drawings, video, and live performance. Music serves as a crucial counterpoint to the character dialogue, connecting the audience to the performance in a more visceral way.

As I write this, we are living out another real-life science fiction which could also be called The Purge and The Day the Earth Stood Still, though without the fantastical sheen of the silver screen. Living with the coronavirus has brought us closer to the tempo of reality TV with its consistent tension, plodding pace, low production budget, and the resounding certainty that there must be something better to watch, and live, than this. Thankfully we have music, and we can find the most sensorial relief there when our minds have become overloaded with a level of uncertainty disproportionate to the amount of information our eyes must take in.

For Focacciatown:Reloaded, I again collaborated with composer Molly Joyce, whose arrangements add a beautiful texture, depth, and clarity to the performance. In Focacciatown, we were joined by JIJI on electric guitar and in Reloaded, by Liz Faure. Reloaded was also performed at the Baltimore Museum of Art (curated by Lee Heinemann) in June 2019 with Sam Garrett on guitar and Atticus Hebson on keys with substantial improvisation. Later in 2020, we hope to raise the funds to record and release this music.

The above video documentation is from the 2019 performance of Reloaded at The Kitchen (February 21 & 22), marking the closing of my solo exhibition Animal Static. Additional support for Reloaded was generously provided by the Foundation for Contemporary Arts.

— Lex Brown, April 2020

BIO

Lex Brown is an artist, musician, and writer. She has performed and exhibited work at the New Museum, the High Line, the International Center of Photography, Recess, and The Kitchen in New York; REDCAT Theater and The Hammer Museum in Los Angeles; The Baltimore Museum of Art in Baltimore; and the Munch Museum in Oslo, Norway. Brown holds degrees from Yale University (MFA) and Princeton University (BA). She is the author of My Wet Hot Drone Summer, a sci-fi erotic novella that takes on surveillance and social justice (first edition published by Badlands Unlimited). Consciousness, a survey of Brown’s work spanning the past eight years, is newly available from GenderFail. Containing documentation from forty-six different videos and performances, as well as thirty-three original song lyrics performed in artist-run spaces, museums, music venues, and galleries, it is Brown’s first book to have been acquired by the collections of the Met, MoMA, and Whitney Museum, amongst other notable institutional collections.