On View: September 8

This Video Viewing Room features new writing by artist fields harrington that responds to three works represented in The Kitchen’s archive: Kerry James Marshall’s Doppler Incident (1997), Butch Morris’s Current Trends in Racism in Modern America: (A Work in Progress) (1985), and Tracie Morris’s Sonic Synthesis (1999). Excerpts from the recordings of Marshall’s performance and ephemera related to all three productions are also included. A recording of Morris’s performance was available to view from August–December 2021.

This presentation is organized by Alison Burstein, Curator, Media and Engagement.

At the outset of my proposal for this project, I began asking questions such as: Who and what have been faded out or silenced in the archives of The Kitchen? How do I recover, recuperate, retell forgotten and shared histories? Why do artists, poets, and musicians resort to the grammar of science? What is the use of the aesthetics of science in a work? What are the burdens of representation?

To resolve some of these questions and unsettle the familiar absent-presence of the archive, I put forward the methodology of Black Secret Technology. I should note here that Black Secret Technology is not my own concept, but the title of an album by the British record producer and musician Gerald Rydel Simpson, better known as A Guy Called Gerald. However, I understand Black Secret Technology as a coded system of knowledge that streams and circulates throughout Black cultural production. It may also be understood as the interdisciplinarity of creative labor and lived experience that endorses a poetics of being. Black Secret Technology refuses to rely solely on the underpinnings of empirical knowledge production, but rather it un/makes and contours the edges of these systems.

Towards the end of this project, I found myself at the edge of what Black Secret Technology is, and naturally, my thinking around this concept began to pivot. I felt at the boundary of my rendering of Black Secret Technology and ran into unexpected limitations of this particular method during the process of writing this essay. One revelation that transpired was acknowledging how BST fails to enact entangled knowledge systems that have the capacity to unmake empirical systems of knowledge simply through the interdisciplinarity of creative labor and lived experience and relying on the essentializing qualities of representation.

So with that said, what I’m attempting to do in bringing together works by Kerry James Marshall, Butch Morris, and Tracie Morris from The Kitchen’s archive is to propose new models of inquiry into the alchemical affinities that are created between these works. These affinities are alchemical because although they are dissimilar in their composition, they still have the capacity to produce new chemical reactions [1]—or more aptly because these affinities are palpable sites for knowledge production.

However, I’m left with unresolved questions, like: What is the scientific value of Butch Morris’s gestural articulation of conduction? How can I situate Marshall’s performance Doppler Incident alongside philosopher of science Micheal Polyani when he says, “a scientific theory which calls attention to its own beauty, and partly relies on it for claiming to represent empirical reality, is akin to a work of art which calls attention to its own beauty as a token of artistic reality”? [2] And how may I trace writer and politician Aimé Césaire’s science of the word in the radically improvisational synthesis of Tracie’s Morris’s performance? These questions could be further explored by spending more time outside of The Kitchen’s archive developing new methodologies that transform systems of knowledge with the practices of embodying interdisciplinary ways of knowing and seeing the world; observing how race, class, and gender are attended to in the history of science; studying the scientific value of intellectual passions (the response to an essential quality in a scientific statement); and constructing worlds less ordered by racist-eugenic logic, anti-Blackness, classism, ableism, and cisheterosexism. [3]

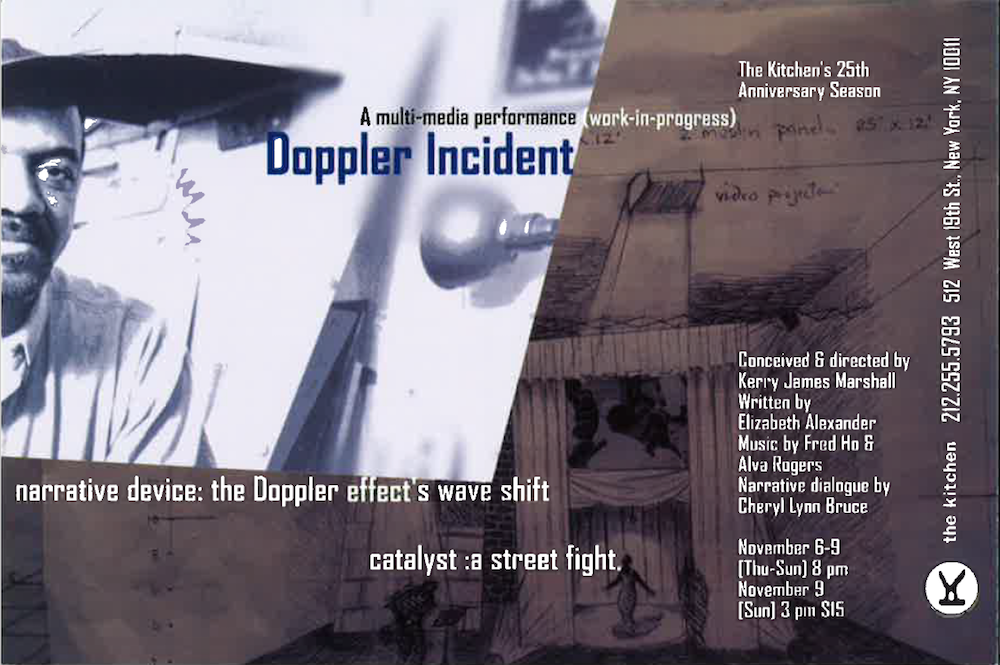

Kerry James Marshall, Doppler Incident (1997)

The epistemological task of Kerry James Marshall’s 1997 production Doppler Incident feels “asymmetrically connective” because he situates personal knowledge with the grammar of physics, and this synthesising operation poetically recodes how we might apply the empirical understanding of the doppler effect. [4] The strategic move away from the use of the word “effect” and the shift toward “incident” displaces the scientific phenomenon (doppler effect) out of its purely objective structure and situates it within the realm of the subjective. An incident can be understood as an occurrence, unlikely chance, or a violent event. In order for incidents to happen, a person or persons have to be present to experience the event of an incident. On the other hand, “effect” is a result, consequence, or an operation. Although people might be involved in implementing effects, they are not always subject to experience their outcomes. So, if we follow this logic, we are conductors of effects and spectators of incidents.

On occasion, the performance is didactic and demonstrative. Performers address the audience, inviting them to observe a demonstration of the doppler effect. A remote-controlled toy train on a circular track edges the stage, and you hear its horn as it moves around the track. One performer goes on to explain how changes in the frequency of waves and true pitch function and relate to each other. The heroes of the performance (in line with Bertolt Brecht’s use of this term) are educators who have the capacity to be storytellers and teachers of the physical sciences. [5]

I’m willing to make the claim that Marshall’s Doppler Incident generates a knowledge system that articulates Black ways of living and knowing. [6] The performance entangles physics with sociality by coupling lived experience with the scientific aesthetics. From the press release from The Kitchen’s archive, we know that the Doppler Incident was “inspired by a street fight Marshall witnessed in Chicago...” and it “employs the Doppler effect to deconstruct Marshall’s chance discovery through film/ video, poetry, music, and narration.” Marshall’s coalescence of the physical sciences and a violent event that he witnessed gives the Doppler Incident the capacity to delink itself from the trappings of imperial knowledge systems that are underestimated.

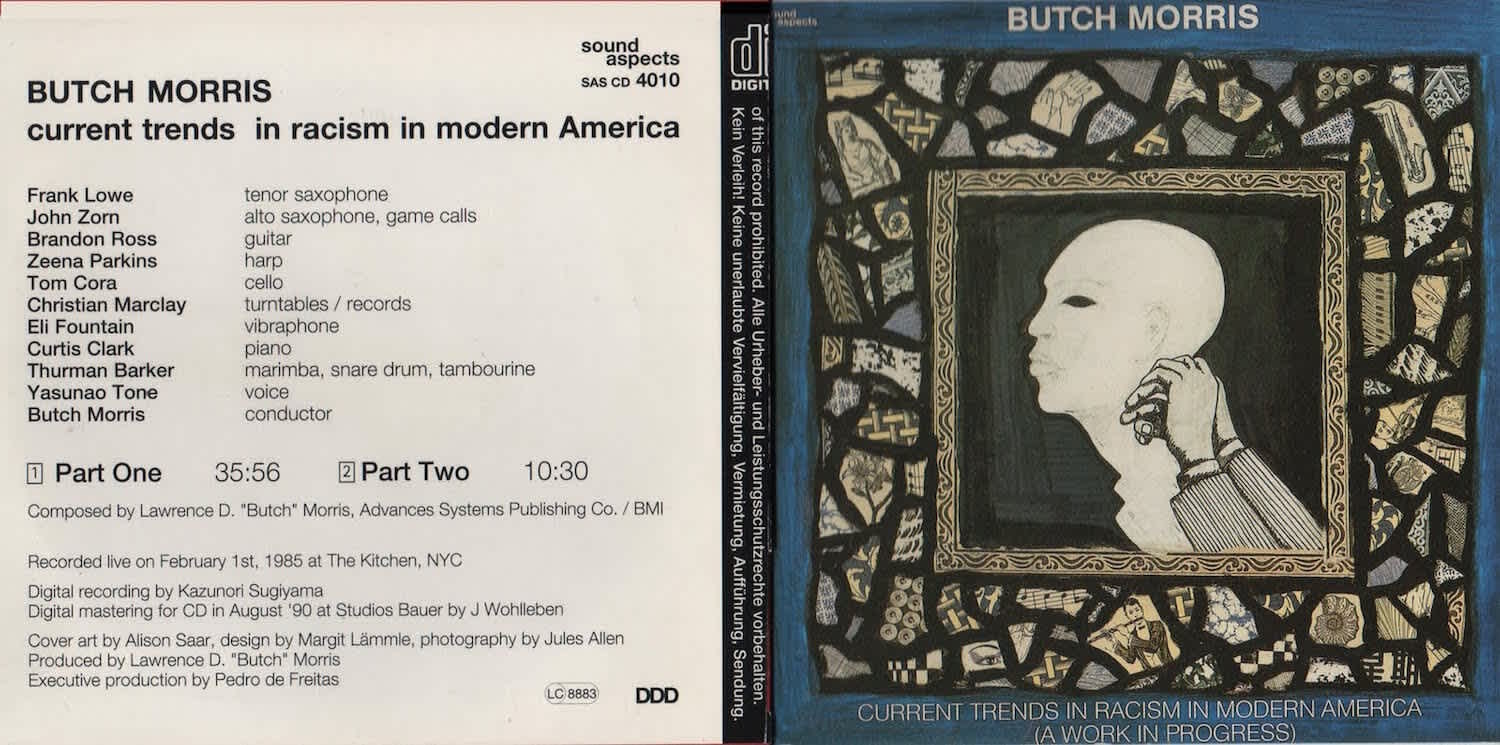

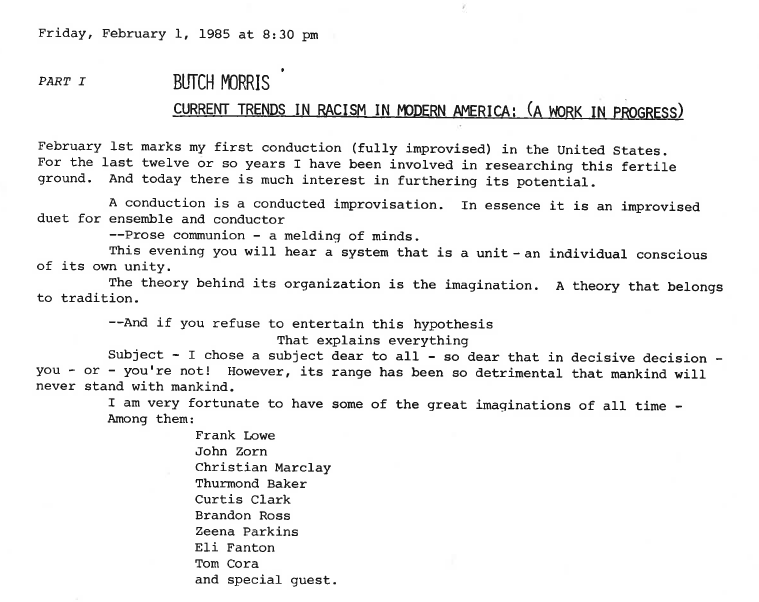

Butch Morris, Current Trends in Racism in Modern America: (A Work in Progress) (1985)

When looking at the scientific definition of conduction, it is described as the process by which heat energy is transmitted through collisions between neighboring atoms or molecules, or as the transfer of heat through matter by communication of kinetic energy from particle to particle with no net displacement of the particles, while taking place in all phases: solid, liquid, and gas. However, when Butch Morris employed the method he termed Conduction®, it’s the physical aspect of communication and heat; it’s the inhabiting of an extra dimension of notation and improvisation; it’s interpretation in real-time; it disrupts our notion of what it means to be a conductor, composer, improviser, and listener; it’s the electricity that flows between conductor and musicians; it’s symbolic of notation just like speech is symbolic of writing; and it is the art of collective imagination.

After twelve years of research, Morris debuted the first chronological Conduction® at The Kitchen on February 1, 1985, in the performance titled Current Trends in Racism in Modern America: (A Work in Progress). The performance featured Brandon Ross on guitar, Zeena Parkins on harp, Thurman Barker on the marimba, Curtis Clark on piano, Frank Lowe on tenor saxophone, Christian Marclay on turntables, Eli Fountain on the vibraphone, Yasunao Tone on voice, Tom Cora on cello, and John Zorn on alto saxophone and game calls.

In the press release of the performance, we’re given a glimpse of Morris’s conceptual frame: “A conduction is a conducted improvisation. In essence, it is an improvised duet for ensemble and conductor / --Prose communion – a melding of minds.”

From an epistemological ground, Morris was producing a local knowledge system that breaks from the outside and within, or, more precisely, what the press release described as “a system that is a unit – an individual conscious of its own unity.” He invented a sonic instruction set that consisted of signs and gestures to transmit information to his ensembles. For Morris, there was a lack of terminology—notations that didn’t exist in conducting, and also didn’t exist in improvisation. This notational scarcity prompted him to develop a vocabulary of idiographics, symbolism, and directives that would transfuse generative information for interpretation in a real-time content structure exchange. His desire was to exploit and manipulate notation through conducted improvisation.

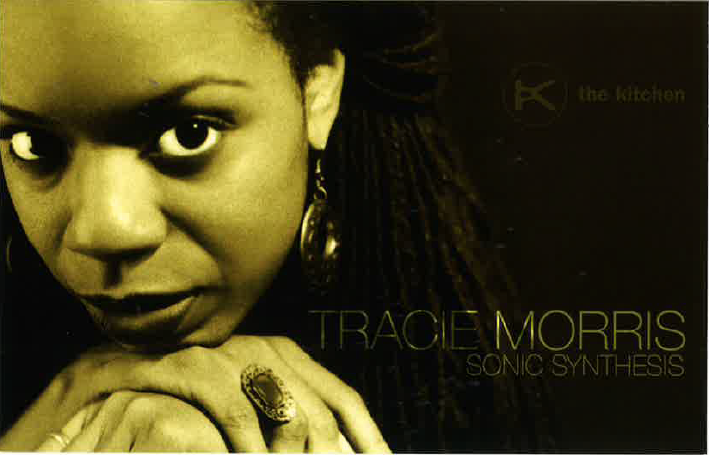

Tracie Morris, Sonic Synthesis (1999)

What is the economy of a radically improvisational synthesis? What happens when improvisation is put into action for liberatory measures? What are the possibilities of improvisation being considered as a mode of invention? I didn’t watch the documentation of Tracie Morris’s Sonic Synthesis, performed at The Kitchen in 1999. I witnessed the documentation of Tracie Morris’s Sonic Synthesis. The performance must be diligently taken in, actively engaged, and closely listened to. Perhaps, more aptly, I listened through the sonic substances of Morris’s utterances tethered to the ensemble of Graham Haynes, Marvin Sewell, Henry Schroy, Val Jeanty, Vernon Reid, and Melvin Gibbs, with the guidance/direction of Arthur Jafa.

Morris’s speech acts generate waves that move through methods of subtractive synthesis (the oscillation of vocal folds traversing to the mouth and throat as a filter), and additive synthesis (the construction of timbre by way of joining sine waves). Phrases such as “cinnamon...sweet like cinnamon” repeat until they cascade into “synonym” and “swimming” with reverberative-like cadence. I understand these moments of her performance as examples of Black Secret Technology and sites for knowledge production and invention.

The improvisation that emerges in Sonic Synthesis isn’t merely an epistemic project. It’s additionally an inquiry into the relationship between Black invention and liberation. All of its sonic information is information for knowledge construction. The economy of a radically improvisational synthesis evokes liberated existence, or, more acutely, it invents liberation into existence. New layers of meaning are conjured through and with the sonic fabrics of stutters, the recalibration of intonation, and the embodiment of language itself.

By inhabiting an extra dimension of notation and improvisation, the performance situates new territories of how we might constitute a new grammar, vocabulary, and/or system of knowledge. This unique inhabitation of the phonic is inventive by virtue of its uncontainable ground. The ungraspable grounds of Sonic Synthesis are alchemical because their inherent meaning is not rendered on the surface, but instead, it requires decoding to capture its precise meaning.

Footnotes:

[1] Chemical affinity refers to the tendency of an atom or compound to combine by chemical reaction with atoms or compounds of unlike composition.

[2] Michael Polanyi, Personal Knowledge: Towards a Post-Critical Philosophy (United Kingdom: University of Chicago Press, 2015).

[3] While writing this text, my thinking was influenced by Donna Haraway, "Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective," Feminist Studies 14, no. 3 (1988): 575-99.

[4] Katherine McKittrick, Dear Science and Other Stories (United Kingdom: Duke University Press, 2021).

[5] Walter Benjamin, “What is Epic Theatre,” in Understanding Brecht (New Edition) (United Kingdom: Verso, 2003).

[6] McKittrick, Dear Science and Other Stories.