Credits:

Sara O’Brien, Winter/Spring 2018 Curatorial Intern

March 20, 2018

"From the Archives” is a series that spotlights The Kitchen’s history. As a complement to our Archive Website, these posts offer focused reflections on the artists, exhibitions, events, and institutional practices that have defined and shaped The Kitchen since its founding in 1971.

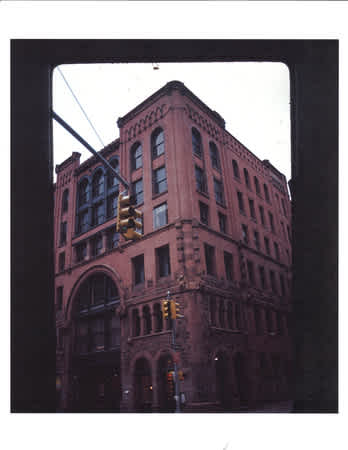

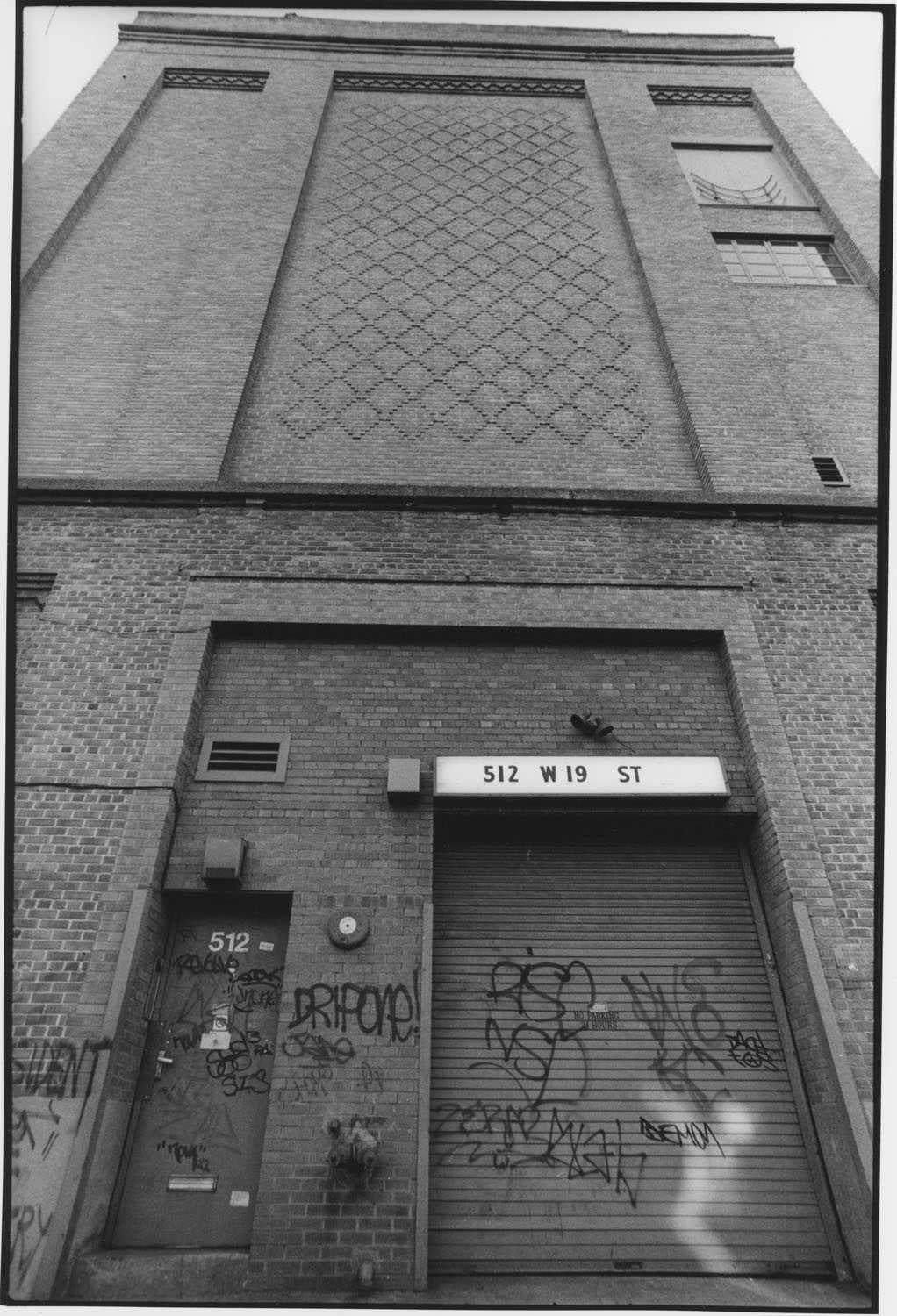

This year marks The Kitchen’s thirty-third year in Chelsea, where the organization has resided in the same brick structure since relocating to this now bustling neighborhood in the fall of 1985. A steady fixture in a vastly altered environment, The Kitchen has presented hundreds of performances, exhibitions, and events that have been attended by thousands of individuals since programming began here in January 1986. For me, working at The Kitchen as a curatorial intern during the past year, this extensive program’s diversity and abundance becomes uniquely resonant whenever a performance begins in the ground floor theater given how a multitude of performers have adapted and refined their craft in this space over the years. In the context of Abraham Cruzvillegas’s upcoming performance Autoreconstrucción—which will take place in this same theater and draw its materials from the streets of the surrounding neighborhood—and amidst the ceaseless rattling of drills in a Chelsea landscape increasingly populated by construction sites, my interest has become directed towards the building itself. At a time, and in a city, where the cultural histories embedded in concrete architectures seem to be so readily erased and easily forgotten, it seems apt to direct closer attention to aspects of this building that The Kitchen has called its home for more than three decades.

The Kitchen’s move to its current residence at 512 West 19th Street was the organization’s second relocation since its formation in 1971 in the disused kitchen (from which it takes its name) of the Mercer Arts Center. Despite always asserting its own distinct identity and mandate, The Kitchen conducted its activity under the larger auspices of the Center until 1973, when it moved to the second floor of the LoGiudice Gallery building in Soho at the corner of Wooster and Broome Streets, officially incorporating as a non-profit institution that same year. As an exhibition and performance space—as well as a central meeting place for artists—The Kitchen during its Soho years featured strongly in the activities and ideas of a burgeoning experimental art scene, forging an international reputation as a proponent of the avant-garde. By the mid-1980s, however, The Kitchen’s identity was in transition, reflecting questions around the direction of its program in a changing artistic context (in addition to the financial difficulties perhaps any non-profit would be bound to face). The staff and leadership underwent significant restructuring, and The Kitchen’s Soho space was sold, both resolving debts and underlining a growing consensus that The Kitchen had outgrown its former space—where noise complaints from the building’s residents had already required The Kitchen to hold larger music events off-site. As Paula Cooper, a board member at the time said, “once it has a new space, The Kitchen will have a new future.”

The move to the far-west streets of Chelsea (not yet the gallery hub it is today) was indicative of The Kitchen’s evolution from smaller alternative art space to an independent, more established (though decidedly not “establishment”) institution. In fact, the location, while largely removed from the commercial gallery circuit, could be said to embody the organization’s cultural contradictions: It was near the Minimalism-minded Dia Center, yet ensconced in the area’s vibrant ’80s club culture. And The Kitchen now had the space and facilities—however raw they still were—to execute in a way it could not before the ideas, proposals, and participation of the artists, practitioners, and public for whom it continues to operate. In an early statement of The Kitchen’s History and Purpose, written just after the move, a telling paragraph indicates how the infrastructure of this new building was, from an early stage, embraced as an environment that could facilitate The Kitchen’s mission:

On an ordinary day at The Kitchen, a performance artist rehearses in the first floor theater space while dancers wait patiently off stage for their turn to work through the beginnings of a new piece. Musicians arrive for an evening concert. A videomaker stops by to check her work in the video viewing room. A painter installs his show in the second floor space. A filmmaker drops off a film for an upcoming screening. The painter talks to the videomaker. The musicians watch the dancers. The filmmaker talks with the performance artist. Ideas and images collide. Interaction and future collaborations develop.

Moreover, while The Kitchen initially rented 512 West 19th Street from the Dia Foundation—who had constructed the facilities that constituted The Kitchen’s performance and viewing spaces, and which had previously been loaned to artist Robert Whitman—within two years (and thanks to the savvy securement of a loan by several board members) The Kitchen purchased the building, fully setting down roots in its new home.

During these early years in Chelsea the architectural history of the building was frequently mentioned in The Kitchen’s publicity material. For example, the inaugural event series at the space was titled New Ice Nights, referring to the building’s operation as an ice storage facility in the early 20th century, a fact explaining the structure’s notable lack of windows that conveniently lends itself well to the construction of the two black-box spaces that make up The Kitchen’s primary facilities on the first and second floors. While this information has since faded from official documentation, artists continue to be intrigued by the specific history of the building, and several have brought otherwise forgotten or disregarded aspects of this past to light again.

For instance, the artist Katherine Hubbard explicitly took The Kitchen’s physical building as a starting point for Bring your own lights in 2016, an exhibition comprising sculptural and photographic works and a live performance in the gallery space. Hubbard utilized the specific trajectory of the building’s function—from its origins as an ice storage facility to its current use as a gallery and theater space—as parameters within which to consider the specificity of constructed space, the production of images as this relates to the body, and contemporary photographic practice, in addition to exploring alternative narratives around cities, class, and image-making in her performance piece.

Another project both stimulated by and structured around the particularities of the building’s history was The Rehearsal, a group exhibition in 2014. Upon finding out that an unreleased film denouncing the Greek military junta who ruled Greece from 1967 to 1974 had been shot by the blacklisted, American filmmaker Jules Dassin in 1974 in what is now The Kitchen’s gallery space, Curator Matthew Lyons invited Courtesy the Artists, Discoteca Flaming Star, and Georgia Sagri to revisit the themes and structures of the original film. The artists’ varied responses each used this specific instance from the past to engage with and stimulate further conversations about the conditions of the present, with the same physical space hosting the exploration of similar issues as those addressed more than forty years earlier.

Similarly, the group exhibition Matter Out of Place in 2012 engaged with themes that related to The Kitchen’s role and position in its broader surroundings. The exhibition presented work by artists responding to ideas around the regulation of public and private space in rapidly changing urban environments and the role of personal histories and the historical knowledge of a building or site in these experiences. Notably, the sculpture and installation artist Fawn Krieger chose to delve deeply into The Kitchen’s archives as a means to consider these questions. The artist’s resulting installation, Property Acts (2012), consists of a variety of sculptures relating to the various periods of The Kitchen building’s use, each functioning as “acts” that retell its untold or forgotten history: its beginnings as an ice storage facility, as a motion picture studio, Whitman’s studio, a performance space, and, finally, as the site of a 1970 fire in which a young fireman was killed. Additionally, each sculpture included a video projection of its own construction, making it simultaneously complete and resolved yet still in process. This co-existence of the solid and static with an element of perpetual change echoes the role of The Kitchen’s building in its operations as the consistent concrete structure in which ever-changing activity continually unfolds.

While many artists have considered the historical resonance of The Kitchen’s building by focusing on its past use, others have investigated the architectonic structure of the brick building, pushing up against its boundaries, investigating its limits, and expanding its possibilities. These artists often return to The Kitchen to perform again, forging a relationship with the space itself through their work and thereby underscoring the significance of this ongoing exchange. One such individual is choreographer and dancer Sarah Michelson, whose unorthodox use of the theater space – most recently for her new work October2017/\ this past fall – in many ways embodies the experimental nature of The Kitchen’s mission. Michelson often removes the risers and rearranges the layout in ways that collapse the divisions of stage and seating, audience and performer. The space itself becomes a site for experimentation, not bound by the conventions of a regimented design or the fixity of permanent features to be worked around.

Another artist who has similarly utilized the dynamic possibilities of The Kitchen’s space is the choreographer, visual artist, and writer Ralph Lemon. Especially germane is Lemon’s 2015 Scaffold Room, which took place across the theater and gallery space as well in the more peripheral spaces of the stairwell and elevator. Scaffold Room was a multi-faceted project that explored the representation of the Black female persona in American culture through a video and sculptural presentation in the gallery, readings of transgressive American literature in a specifically designated Graphic Reading Room, and performances in the ground floor space. Pertinently, Lemon described Scaffold Room as a “flexible architectonic space” and as such The Kitchen provided the malleable architectural framework within which Lemon’s conceptual concerns could be parsed out.

Also drawing on the flexibility of The Kitchen’s spaces, visual artist and choreographer Yve Laris Cohen conducted the performance Fine in 2015, which reflected upon the broader ontology of the theater versus exhibition space. The theater space was stripped of all its theatrical accouterments so that it could function as a fluid and interstitial space, and through interventions involving the basic components of architecture—floors and walls—Laris Cohen problematized the terms “black box” and “white cube” as they refer to physical spaces and to the fields of dance and art respectively. The performance aimed to subvert the rigid designations that often define the activity in a space or an established discipline, rendering such boundaries porous for future activity in a way that befits the experimental and interdisciplinary nature of the program at The Kitchen.

As The Kitchen nears its 50th anniversary, it may also reflect upon its time at 512 West 19th Street in Chelsea, an area of New York City significantly changed since The Kitchen settled here more than thirty years ago. The building is imbued with the residues of its many histories and, as The Kitchen, continues to accrue the reverberations of the performances, exhibitions, and events it houses. The building’s interior has been adapted and improved over the years (the most extreme alterations necessitated by the damages caused by Hurricane Sandy in 2012), but from the outside it looks much the same as in 1985. This exterior consistency mirrors the persistence of The Kitchen’s commitment to its core values, which have not wavered in that time or since its formation in 1971. And today, although The Kitchen has become firmly embedded in its location, the capacity for alternative engagements and the illumination of unnoticed elements within these four walls remains as dynamic and open as ever.