Credits:

By: Josh Sanford, Curatorial & Archive Intern, 2024–25

July 9, 2025

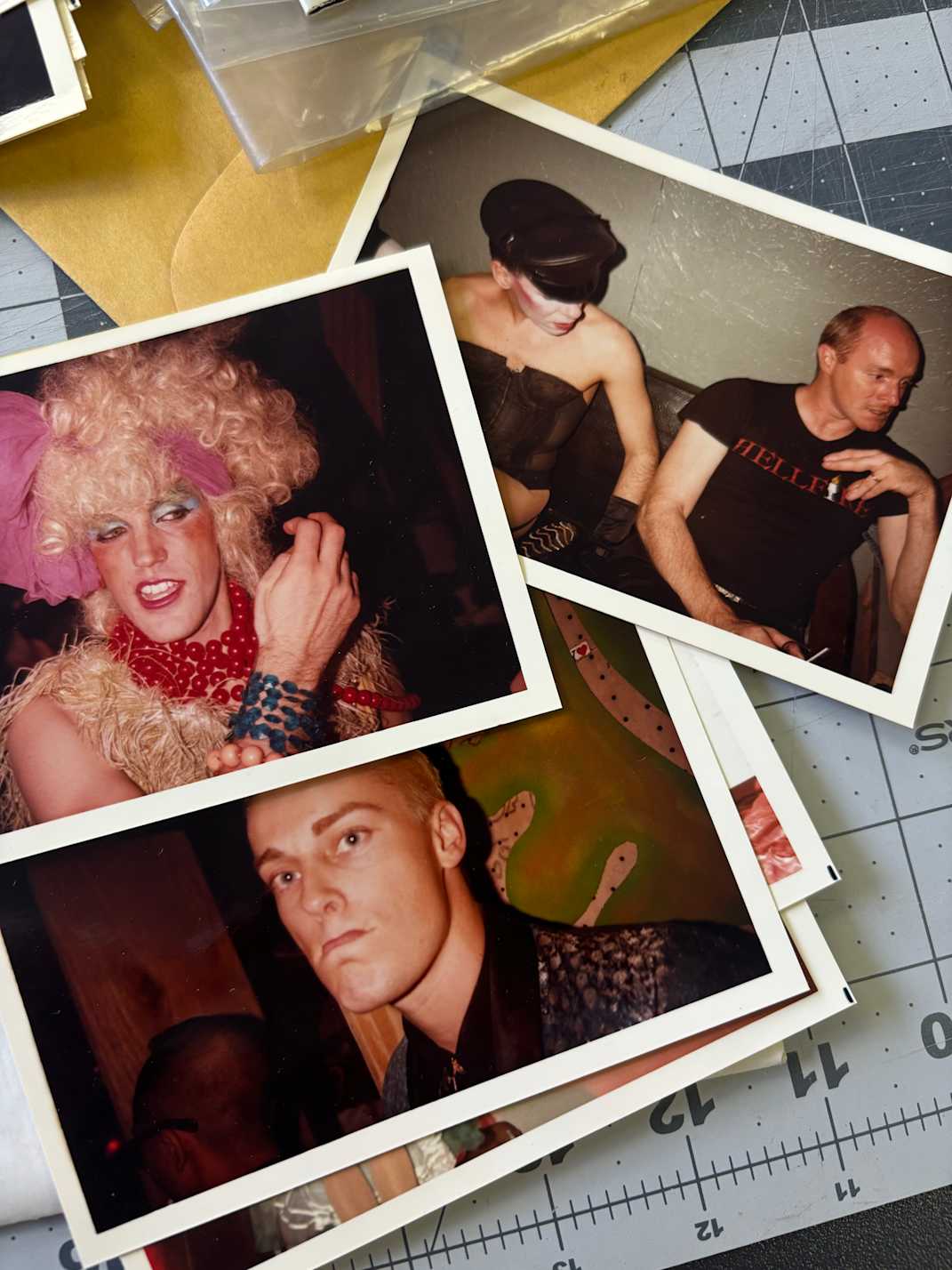

High heels communing with cheap cocktails atop the counter, chicken feather boas gliding along bare shoulder blades, and wig tops protruding through blue-white smoke—these noticings all compete for the eye’s attention at The Pyramid Club, a sloppy dive joint tucked against the Southern corner of Tompkins Square Park off Avenue A. DJ Sister Dimension spins the latest Italo Disco hits over the sound system, shouldering the hot buzz from the crowd into the pockets of the dim narrow bar. The year is 1986 and it’s a Sunday night, which means it's the night of Whispers, Pyramid’s off-kilter gay cabaret hosted by performance artist, Hapi Phace.

Hapi introduces Lady Bunny following performances by Audrey White and Wendy Wild. Lady Bunny’s lips outline the edges of each word to “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” as she conducts the audience with face-up palms, delivering emphatic biffs into the open space above the crowd. Uptilted applause tides into a clamor punctured by shrill whistles as the air between Bunny and the crowd grows thick with the kinetic energy of the East Village. The audience is composed of deviants (in one way or another) brought to the neighborhood by affordable rents—a countercultural mélange curling up off the cracks in the floor like a beautifully damaged inflorescence.

Tom Rubnitz—a young, bright-eyed video artist from Chicago, Illinois—moved to New York in 1978, and by 1981 was already collaborating with the other misfit artists in the downtown club scene including many of its biggest stars like Bunny, Tabboo!, John Sex, John Kelly, Ann Magnuson, Lypsinka, and Ethyl Eichelberger, to name a few. These same playbill headliners became some of his most recognizable castmembers. Cradled in the rip of HIV/AIDS and television’s historical currents, Rubnitz couches his videos in a distinctively chromatic visual aesthetic, screening an affective condition of sustained grief and surfacing a derisive criticism of TV in his abuse of the form.

Rubnitz's oeuvre captures the essence of his downtown scene. Inspired by his childhood spent watching television, Rubnitz leveraged the still-nascent art medium of video to eternalize otherwise underground figures and happenings from 1980 up until his death in 1992. Rubnitz's videos are zany, irreverent, and, sometimes, humorously ordinary. He may feature pink and green pastel-skinned performers wearing mixed-patterned costumes and long feathered eyelashes. Or he might follow a gaggle of drag queens around as they gallivant through Central Park, down 5th Avenue, and round and round the white halls of the Guggenheim. In another video, he records a chicken casserole recipe.

Pulled into the orbit of the nightlife circuit, Rubnitz and his friends/collaborators frequented spots like the Pyramid Club, Danceteria, and Club 57. These clubs weren’t just gay, and they certainly weren’t just dancefloors. They were explosively indeterminate: spilling out from between their graffiti-stained brick walls was a punk-laced moxie drunk on the fluorescent sweat of New York’s premier freaks. The opening scene of this essay, cobbled together in my imagination through a blend of various written and video records from the internet, represents only a tiny offering of this eruptive subculture.(1) On any given night, stumbling into these clubs could bring you in front of a punkster show, an experimental video screening, an obscure play, an art installation organized by the likes of Keith Haring and, occasionally, all of the above.

These kuntsthalles-of-sorts, markedly different from highbrow art galleries and other institutionalized exhibition spaces, spawned a playful experimentation of their own, stoking the flames of a gleefully aberrant avant-garde. With its shared affinity for performance that not only pushed boundaries, but effaced them altogether, The Kitchen welcomed a handful of artists who got their start in these nightclubs.

In April of 1992, The Kitchen screened Tom Rubnitz: A Video Retrospective. The month-long retrospective, held in The Kitchen’s Video Viewing Room, included a premiere hosted by Lady Bunny with performances by Ann Magnuson and the mononymic doll, Frieda. Sixteen of Rubnitz's videos made between 1983 and 1991 were on view, ranging from spoof TV commercials, to music videos, to “rockumentaries,” to public service announcements.

Rubnitz's work responded to interlocking exigencies and cultural conditions of the mid-80s. The queer and artist communities of New York suffered as the worsening HIV/AIDS epidemic ripped through the city. While TV stations everywhere saturated their broadcasts with alarmist misinformation, the Reagen administration was reluctant to address the public health crisis at all. In the four years between the first reported cases of HIV (1981) and Reagen’s first public mention of AIDS (1985), TV had done a number on the public’s understanding of the disease, its transmission, and its affected populations. Meanwhile, around the same time, the introduction of the TV remote, the popularization of the Video Home System (VHS), and proliferation of channel options denoted the decadence of network-era TV. Rubnitz adhered to this newfangled form of TV, levying its novel interactivity to satirize TV’s role in cultivating antipathy.

One year before the retrospective, Rubnitz's work had appeared at The Kitchen for the first time. Three of Rubnitz's videos (Undercover…ME!, 1988, Strawberry Short-Cut, 1989, and Pickle Surprise, 1989) were included in a video appetizer prepared by Charles Atlas for An Evening with Charles Atlas. Later in 1991, on December 1, Atlas would return to The Kitchen for the third annual “Day Without Art” to direct a live broadcast of We Interrupt This Program in collaboration with Visual AIDS. Rubnitz's 30-second PSA, Summer of Love, produced for the American Foundation for AIDS Research (AMFAR), was featured in the broadcast among a series of monologic performances and informative clips on safe sex.

Situating Rubnitz within these institutional contexts shows that Tom Rubnitz: A Video Retrospective took place as the energy around television at The Kitchen was steadily increasing. In the spirit of media theorist Marshall McLuahn’s claim “the medium in the message,” The Kitchen and its artists, including Rubnitz, have a long-demonstrated interest in TV and its appurtenances as experimental formats fit for self-conscious exploration of TV’s reach and effect. From Cable Review Lounge (1984), to its TV Dinner series inaugurated in 1998, and into the present with Lines of Distribution and Code Switch (both 2024), The Kitchen has had its eyes and ears pressed against the small screen for decades.

Drawing on TV ads, many of Rubnitz’s works in the retrospective were short-form, including the sickly sweet Strawberry Short-Cut, a minute-long commercial for Lady Bunny’s easy-to-prepare dessert hack. Rubnitz riffs on the commercial format, using the video to advertise a donut dressed in jelly, cherry 7UP, whipped cream, and fresh strawberries. The dessert’s superfluity, a stand-in for a ripening neon consumerism, compounds with Rubnitz's visual language to underscore an aesthetic rejection of the emergent professional-class masculinity hatched by the rapid accumulation of wealth on Wall Street and its corollary cultural fixings.

Beyond his stylistic refusal, Rubnitz takes a wry jab at the television landscape itself in another work screened in The Kitchen’s retrospective, Made For TV (1984), which consists of short clips with static bookends. Ann Magnuson stars in the 15-minute-long mixed bag of TV programs and ads— the sole actor performing the role of 35 different oddball characters. In one scene, Magnuson sports a shiny blonde wig and nice jewelry as Tammy Jan of Tammy Jan Ministries. The TV evangelist implores viewers to dial 1-800-666-CASH to make a $1,000 monthly pledge. She insists, as she wipes away unconvincing tears,“That’s very little… I mean how am I going to pay for my dry-cleaning bills!?” In another recurring bit, she is Kimberly Crump, a newscaster for News at Noon, sharing word of impending Soviet missiles. “More at six,” she reads, matter-of-factly.

Quick cuts from one scene to the next reflect the recent developments of multi-channel transition and the introduction of the infrared remote control, both inventions that allowed for greater interactivity for TV audiences. An increase in channel options and the arrival of VHS democratized the TV viewing experience. Empowered by heightened agency, watchers could overwhelm themselves with what they wanted, when they wanted it, without getting within a few feet of the magic box. Time and space became dislodged from routine, thrust into the press of a button. Innerved by this moment in television history, TV did an about-face, turning to flirt with the lucrative prospects of an audience made up of individuals. This paradoxically entrenched TV’s cultu-ritual authority even as it retreated from a singular source.

In Made for TV, Rubnitz hijacks the medium, wresting the new-found control from the viewer by taking up the action of flipping back and forth across channels. This intervention serves a nipping critique of TV, suggesting the institutionally allotted agency to be a farce: no matter how much channel-surfing you do, you’re never really the one with control.

The soft impression of fun-colored hues and laughs left behind on audiences in most of Rubnitz’s work lets on a dynamic apprehension of grief. Rarely outright with its expression of sorrow or anger toward the loss collectively being experienced during the AIDS epidemic, Rubnitz’s documentation of whacky food inventions, drag queen festivals, and suggestive nightlife performers distills grief’s multiplicity when sustained over long periods of time. That is to say, Rubnitz’s work doesn’t posit joy or humor as counterweights to grief. Rather, it asserts joy and humor as affective animations of grief, thereby rendering an embodied queer subjectivity protracted and in flux—magnetized between seemingly counteractive emotive poles and punctuated by efforts to negotiate incalculable loss. Given this, the division of Rubnitz’s work from the more pointed art that his contemporaries were showing at The Kitchen and elsewhere about AIDS yields an irrational, depoliticized quotient.

In 1992, the same year the retrospective screened at The Kitchen, Rubnitz collaborated with artist, writer, activist, and Kitchen alum, David Wojnarowicz to create a new work. The video, titled Listen To This, is a departure from Rubnitz's signature vibrant, alien world. Wojnarowicz, wearing a navy blue suit and with his hair slicked to the side, sits in front of drawn blinds. In the first half of the video, he speaks in first-person as television. Here, the medium is the messenger: “My job is to give you a false sense of comfort, or safety, or fear, or confusion,...to make your life a schizophrenic hell.” (3)

Halfway through, the blinds open and a shadow arrests Wojnarowicz’s now-backlit face. At the same time, Wojnarowicz’s script unfastens from his mouth, the audio slipping into a reverbed voiceover before a cut to black. For a total of five minutes, the black screen remains as Wojnarowicz’s narration continues. Rubnitz interrupts the still blackness just three times with moving images: A scene from Ben Casey, a medical drama from the sixties; footage from an ACT UP protest; and a reprise by Wojnarowicz shown removing his tie. These short clips offer only momentary relief from the dense slant of the black block, which repossesses the image each time. Writer Allison Simmons contextualizes interventions like these in appropriations of the television form: “Television’s juxtaposition of banality and real human disaster creates a moral and aesthetic numbness, encouraging passivity, even apathy and manipulability.” (4) Rubnitz sticks a fork in this function of TV as Wojnarowicz’s serrated words bodilessly saw away at our mutual inheritance: a “diseased society” that sanctions violence by way of neglect and distraction. (5)

Television’s role in bringing visibility to AIDS was crude and inadequate, to put it politely. In Atlas’s live broadcast We Interrupt This Program, writer and artist Ron Ehmke states, “AIDS is still a television spectacle, an abstract phenomenon embodied by TV detectives, human interest stories on the evening news, and now TV sports legends. Our initial understanding of the crisis has been as fragmentary, disjunctive, and remote as the experience of watching TV.” In this way, television flattened its audiences into supine consumers, manufacturing consent for targeted neglect by distributing and commercializing ignorance. (6)

Listen To This, unfinished at the time, was not included in the 1992 retrospective at The Kitchen and, therefore, is not represented in The Kitchen’s archive. Its sedated visuals (see “aesthetic numbness”) bear little resemblance to his other videos. The absence of his soft confections, taking the form of a sharp black square, is a reminder of their familiar presence in past works. As such, soft and sharp naturally recall one another like consecutive notes in a refrain

Placing Listen To This in conversation with Rubnitz’s works screened at The Kitchen is an activation of The Kitchen’s archive that reverses the impulse of diving into an archive. While the archive served as my starting point, I’m slingshotting away from it; I spoke with many folks, affiliated and unaffiliated with The Kitchen, who knew him in New York or, like me, have come to be involved with his work. It’s in these exchanges where memory keeps.

Institutional memory, like a Hollinger box, unfolds along sharp seams and—try as we might to hold on— we lose things to the creases. But even if we were to compile every document relevant to Rubnitz in one place—one folder—the goal of circumscription still misses the point. Remembrance is constellatory; it’s a concerted effort enacted across various individuals and institutions.

The same year the retrospective screened at The Kitchen and Rubnitz and Wojnarowicz made Listen To This, both artists passed from AIDS-related illnesses. Following his death on August 12, 1992, The Kitchen hosted Rubnitz's memorial on the evening of September 14 in its Chelsea building. I discovered this fact in an interview, saved in The Kitchen’s internal cloud file server, between Tere O’Connor and the performance duo DANCENOISE. Lucy Sexton, one half of DANCENOISE, casually mentions Rubnitz’s memorial—her brief description of the service forming the only institutional record of this event at The Kitchen.

The relationship between soft and sharp that unfurls here comes into view strangely, overlapped and in pieces. It splits through memory and imagination as a flash of static between channels.

FOOTNOTES

- 5ninthavenueproject is a digital archive dedicated to the video works of Nelson Sullivan who documented the downtown club scene throughout the eighties. The prototypical vlogger, his videos can now be found on a YouTube channel under the same name created by his partner Dick Richards honoring Sullivan’s memory. https://www.youtube.com/@5ninthavenueproject.

- Marshall McLuhan and Quentin Fiore, “The Medium is the Massage” (New York: Random House, 1967).

- Tom Rubnitz and David Wojnarowicz, “Listen To This,” 1992. 15:30. https://www.vdb.org/titles/listen.

- Simmons, Allison. “Television and Art: A Historical Primer for an Improbable Alliance.” Introduction, 7. In The New Television: Video After Television. New York, New York: no place press, 2024.

- Rubnitz and Wojnarowicz, “Listen To This”.

- We Interrupt This Program, directed by Charles Atlas (The Kitchen and Visual AIDS, 1991). 18:15. https://archive.org/details/XFR_2013-08-29_1A_07.

- Sexton further describes Rubnitz’s memorial in a contribution to the catalogue, titled Lost & Found: Dance, New York, HIV/AIDS, Then & Now, published in correspondence with “Platform 2016: Lost & Found” a Danspace Project series curated by Kitchen alumni Ishmael Houston-Jones and Will Rawls. https://danspaceproject.org/2016/11/08/memory-palace-lucy-sexton/