Credits:

Matthew Lutz-Kinoy, Legacy Russell, Angelique Rosales Salgado

October 19, 2023

In conjunction with the newly commissioned project Matthew Lutz-Kinoy: Filling Station, Legacy Russell, Executive Director & Chief Curator, and Angelique Rosales Salgado, Curatorial Assistant, The Kitchen, speak with Matthew about process, performance, archives, and collaboration.

Angelique Rosales Salgado

Matthew, let’s begin by talking about your first encounter with the Filling Station ballet. How did your ongoing pursuit of research emerge into a desire to imagine / reimagine this work at an expanded scale?

Matthew Lutz-Kinoy

I want to call back to the first interview I did with Legacy for BOMB Magazine, because so much of this project has been about encounters and collaboration, and when we did that interview with you, Legacy, and Sophie and myself years ago, I remembered that actually my first proposition for Filling Station (which began in 2020) was preceded by a different proposal to create a touring modular set design that would be for public concerts for Sophie's music. There was this idea to do this big elaborate modular set that would travel and tour to public spaces like Central Park, and I started to have a conversation with The Performance Agency founded by Yael Salomonowitz.

The conversation led to them proposing to me to do a work in public space alongside the river in Vienna that would be seen as boats were passing by, and that was cut short because of COVID health restrictions. It was salvaged into this video shoot that I conducted the dance research with a group of dancers in Vienna, and that project had all of the seeds of the show at The Kitchen.

It had a collaboration with Eckhaus Latta, and it started the music collaboration with James Ferraro. So thinking about this idea of scale, this project started already with these flexible scales. It was supposed to be in a public park, and then it was translated into a film shoot. There was always this idea of the scalability of the project that had its core in the reference material of the filling station.

Legacy’s prompt challenged me to dream about this project in the scale that I found appropriate for this work. It led to an expanded understanding of the relationship to the collaborators even more than site, even more than scale. It was like the ambition and the scale of the depth of the collaboration.

Angelique Rosales Salgado

To foreground that further, could you describe your relationship to this question of set versus site in your practice and in the context of Filling Station. The original ballet performed for a stage was sited at this imagined gas station in the middle of nowhere and in this restaging at The Kitchen, the two performances unfolded across a very public, heavily trafficked site, a gas station in the West Village followed by the performance in the galleries at Dia Beacon. How are you exploring and entangling different architectures and definitions of landscape within and beyond this project?

Matthew Lutz-Kinoy

I love hearing this question because it gets to such a important point of the Filling Station project—which is seeing the United States as an expanded massive site, and the representation of such a national identity like a United States identity, as a state of embodiment expressed in liveness through pantomime and dance language. This question provokes me to say that there's these scales of site, which are a continental scale and then an American scale. Then there's this other site that's also mirroring that, which is the national identity hosted by a body, which is also the site. Then of course, it spirals further into this kind of location, hosting the site of Horatio Street Gas Station or Dia Beacon.

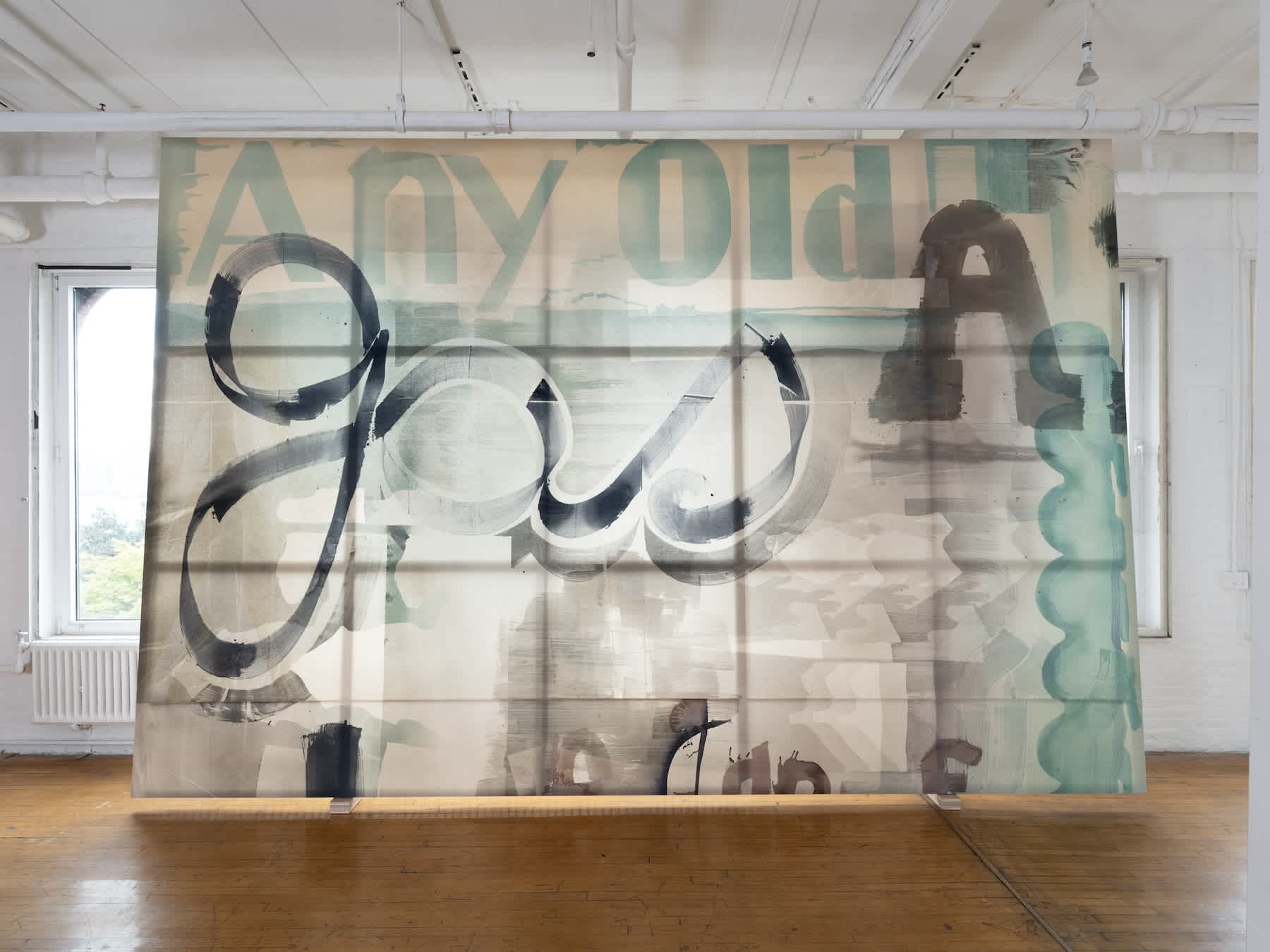

There's another site at play, which is the backdrop paintings. There are the large format works, which act as the backdrop—at their core the paintings for me have always been about collaboration due to their scale and their engagement with architecture. Due to that scale, they also engage with the body and with the bodies of people around them. A few years ago, I started to exhibit my paintings in public spaces outdoors, like at the Sharjah Biennial or at the Geneva Sculpture Biennial. The paintings were placed outdoors, they're exposed to rain, they're exposed to the sun. This engagement with sight and the public site started this possibility of an expression in public space for me.

Inside of the site of The Kitchen at Westbeth, which was used for rehearsals [and now for the exhibition], there are a series of paintings which formed, historically referencing the context for the rehearsal process, which is what I call the brain of the project—it is the site with all the information in it. Then that research and that experience was transposed onto the Horatio Street Gas Station and paralleled this. That’s kind of the idea, paralleling the historical relationship that the Ballet Caravan had to touring.

We had this possibility and this imagination to transpose this kind of historical precedent of the Ballet Caravan and transpose that idea, like a historical idea of their touring onto this mini tour of our production going upstate, which is actually physically closer to Connecticut and to where the original piece premiered in 1938.

Angelique Rosales Salgado

Matthew, your paintings collapse the idea of a stage inside of a painted space. They become a platform, a space of representation, an indexical object. The works are also creating a refigured and culminating site for research—gestural, visual, tactile, architectural references that emerge at an overwhelming scale, drawn from your time spent with the visual archival materials across institutions. It was really breathtaking to see and feel the dancers explore and develop movement within a loft and translation of paintings, how painting might grow out of and translate performance.

Matthew Lutz-Kinoy

This question speaks to what I was talking about, about the ideas of a kind of picture plane and the sort of collapse of that or the layering of that. In the exhibition space, even in the exhibition design of the space, there's a physical layering of those spaces in the visual picture plane that the paintings are able to do, where you are literally looking at a historical document visually layered on top of the backs of the paintings. Then when you flip to the other side, all the paintings are physically layered on top of each other, inside of your picture plane. What I also want to link to is this kind of visual element of the chance of interaction, the chance of seeing something happen simultaneously, the chance of simultaneity, the chance interaction of movement and the presence of a physical body inside of all of these chance interactions of the picture playing.

Legacy Russell

Matthew, I would love for you to break that out further. Angelique has proposed in our discussions this idea of a queer semiotics and what that might look like specifically in relationship to class dynamics. How of course that engages the selection of music and how that arcs from that originating Filling Station to what you now have kind of re-coded and recontextualized within a contemporary setting.

Can you talk about the relationship between the archive and its position as this historic site, but then also what it means to have this be a queer proposition—the archive in itself as a kind of living material that will carry forward from this point as you've kind of recreated and restage parts of that history now?

Starting with the question of what it means to have this idea of an archive be queered over time.

Matthew Lutz-Kinoy

I have to bring it back to the body when you talk about this because so much of this project took place, of course, in physical and digital archives, but my interest in dance is really related to the body as an archive and the body's experience as a type of movement archive. This comes from my background with dance and Judson Church, and with the quotidian movement in dance practice. Really, I am not an archive artist. There's plenty of people who make their whole practices about archives.

I'm not a specialist in using archives as an artistic palette, but I do think that my relationship to art production across many different mediums is a relationship to a kind of historical object and trans historical motif. This is something I've also explored in ceramics, and something I've explored in painting and also in past performances. The use of the archive in this sense is in a way, a type of illustration of the way that this piece as a whole comes into existence. It’s both a kind of window—to quote in a way things that have been haunting me for many years—like the idea of Jose Esteban Muñoz’s Cruising Utopia window. That window is something that's built out of the archive material. I think when you look through that material, you can arrive at seeing the image behind the window, which is all of the work produced in the show. It's sort of like the archive itself and the exhibition is a merging of time.

It's a collapse of time, and it's emerging from time. I constantly think about this space that is the space of queer performance and the exploration of potential worlds as not only the exploration of what those potential worlds are, but the active creation of those worlds through enacting them in space in real time. The archive actively plays a role in that the historical documents play a role in imagining a queer presence in a queer present tense. It's strange to say that out loud because they're literally pictures of dead people and objects that are static, but if you're thinking about how objects come into existence as an accumulation of historical motifs, it makes total sense. It's like when you look at an ancient piece of pottery and you see the way that the flower is drawn on it, and you can find pottery from hundreds and hundreds of years ago with that same flower drawn on it. That's how I see those documents in the show.

Angelique Rosales Salgado

Your last performance project in New York City was a collaboration with Tobias Madison at MoMA PS1 in 2016 and you've collaborated on many performances with Jan Vorisek previously, as well in your deep collaboration with Isabel Lewis where you've experimented with modes of exhibition making and dialogue with movement rehearsal and liveness. We've all really felt that this project has kind of taken up site specificity as being about relationships. In Filling Station you’re exploring collaboration with not only choreographers Niall Jones and Raymond Pinto, but also with musician James Ferraro who created the musical score, and Eckhaus Latta who designed the costumes and who you’ve also collaborated with before, and of course the seven dancer ensemble. How has the collaborative process that has followed your practice for so long, evolved and expanded for you here at The Kitchen?

Matthew Lutz-Kinoy

Something that I’ve learned a lot from this project was taking a chance on people—it was the first time in my own work that I ever worked with people that I wasn't intimately friends with. I wanted to challenge myself to see how that could pan out to collaborate with people that I wanted to learn from, but I didn't know what they were going to teach me.

I knew that I was inviting people into this project for specific reasons. For example, James Ferraro, I knew his music and even didn't know all of his music, but could identify something extremely American in his music, which was also something that I tried to address in these collaborations with everyone. Inside of everybody's practice who joined this project there is an identification inside of people's work within a United States identity. This doesn't mean that everybody in the project has a passport, it means that everyone in the project uses American-ness or the United States in their practice, whether that's in their backgrounds, in their education, or in their modes of expression.

I found James’s use of sampling and his use of synthetic sound to relate very closely to popular forms of media in the American landscape and the United States landscape. What I hear in James’s music and practice a lot of the time sounds like music for television, which itself is something extremely American. It relates very much to the history of media in the United States and popular entertainment culture. Eckhaus Latta is labeled as an American, United States based American brand. They're very much labeled that way in public space.

All of the dancers were chosen by me, and then the selection of the casting was refined with Niall Jones and Raymond Pinto's collaboration. Everyone was chosen to participate because they represented various elements of a spectrum of dance experience. To the core of your question, which was a significant insight for me, is that my proposal for this project—what I shared with everyone in writing in preparation—was relatively simple when I explained it to Niall and Raymond. I wanted to have dance artists in this piece who had unique experiences and who expressed different sides of dance in terms of their backgrounds and movement.

I thought it could be interesting to work with people that had their own unique complex experiences, but also at the same time didn't have these layers of time placed on that. I could say we're all relatively within a similar age range, but there is a youthfulness actually that deals with youth in a way inside of the ensemble. Not that people's experiences are singular, but people's experiences could be slightly less deeply layered in terms of modes of language that they would employ in their dance. In terms of all the kind of accumulation of information that happens in your body. There's less accumulation based on experience and age. So, that was also part of the thinking process and the kind of casting.

What we didn't anticipate was that everyone’s relationship to the rehearsal room more broadly would be so dynamically varied, not necessarily just because of their dance backgrounds. Their experiences of the definition of rehearsal were so diverse that it proved extremely challenging and generative to ask everyone with such different practices and backgrounds in dance experience to physically dance with each other. When I was explaining it to a visual artist I was talking to, I said, “Yeah, can you imagine bringing a bunch of painters into a room that all have extremely different relationships to painting and then asking them to make a painting together? It would be a total mess.” I mean, it would be, I don't know if I could kind of do that in that I sort of realized what I was asking of the group was to do that.

Legacy Russell

What's also really interesting about that is that this is where creating an object and working with people functions differently. And so the models and methods of collaboration are also in some way a mode of community building, and that really is part of what this work became about.

Matthew Lutz-Kinoy

It's exactly what this work was. A big part of this work was my impulse in the beginning because I didn't have that lived experience of creating the work. My impulse was a kind of live action role playing of this kind of historical object. I was like we'll bring everyone together to kind of play this Renaissance Fair of the 1930s. What appeared even stronger inside of the live work was the dancers themselves, and not even a kind of merging of a historical document. There was a merging of the dancers themselves and a historical object, but not a historical character or not a historical dance movement. What really appeared was the kind of the stage itself. The larger stage outside of the conceptual stage of the place within this project was the original ballet, and the dancers themselves were dancing their own experiences on top of that stage.

Angelique Rosales Salgado

Something really thought provoking and intimate from that 1938 Ballet Caravan catalog is what Lincoln Kirsten writes about this “mythical world of a filling station focused in the eyes of a painter and a choreographer” and that specific kind of energetic push and pull between them. All of us inside of the rehearsal space experienced and were inside of the development and evolution of that kind of relationship between you and Niall as choreographer, even from the long conversations you were both sharing before arriving to rehearsal as the space where the work really develops. Can you talk a little bit about the depth of your collaboration together?

Matthew Lutz-Kinoy

I was calling Niall a psychic social worker. He had to read everyone's mind in the room and communicate with each person based on his perception of what they were available to understand. This was absolutely incredible to witness, and probably exhausting for him to absorb all that information. When I met Niall for the first time, he came to my studio in Paris while he was doing a teaching trip with his students from Philadelphia which he does every year. I really lucked out in finding this collaborator and finding that relationship, because I ended up really enjoying all of the time I got to spend with Niall—his generosity and his curiosity and the way he works. When he came to the studio, I took him to a really delicious little restaurant nearby.

It was him, Julien Laugier, my studio manager, and myself. Niall said that he would have a glass of wine with lunch—that already was exciting to me because I was like, oh, this person also wants to enjoy this time together. Then he explained to me that he knew a lot about wine because he used to work in a wine shop and sold wine, and I don't know, something about that made so much sense afterwards when I saw how he worked with people because there's a kind of relationship to, I guess for lack of a better word— the terroir. The terroir of the rehearsal space that was able to access all of this sensibility inside the room, like a kind of nuance and sensitivity. It's not red or white, it's like pink, it's golden, it's natural, and biodynamic. It was amazing the way he was able to have a kind of sensitivity of experience. The conversation with him started the same way. It started with almost everybody in the project.

The starting point of our collaboration was based on all of the archival material that I had researched and presented. Niall was quite curious about all the art historical documents, but really not tied to them. His relationship to the collaboration was very much in the present and very much in close dialogue with the performers. Whereas I was contributing a kind of historical pivoting point and a constant framing of the project—an active framing that was there even before the project began, historically contextualized. Then while producing it, the collaboration brought up different questions about documentation that would continue to reframe itself through photography and video. It was a constant repositioning and reframing of the material, and that's what I think that in combination with Niall’s ability to work so dynamically in the present and to the present created a very interesting dynamic. In that historical text that you are talking about from the old playbill, the painter, which I guess would be me, I do make paintings, is actually the documenter is the person who captures the image.

Legacy Russell

Matthew, can you talk a little bit about the relationship between how some of the genesis points of the project, the community around the project, and the mode of collaboration came into being when sited at the Horatio Street Gas Station in public space mid September as opposed to rehearsal space, and then of course the experience of that being a Dia Beacon on September 23. What was your experience in terms of how each of those sites informed the imagination of the project and what did it mean to be, in the gas station's case, in a private and public enacting a project that of course had been intensely intimate inside of a site and now was with a public view on stage. It was an unusual site to begin with—a blurry location that blends different tiers of spectators and engagement—and then in Dia’s case, inside of the enclosure, this institution of Dia, but of course still with a different model of relationship and porosity between private and public.

Matthew Lutz-Kinoy

By including these two sites, it created an autonomy in the work, which was very strong. Niall was brought into this project because I saw the way he engaged physically with space, especially in his recent solo work C O M P R E S S I O N (2022) at Performance Space. The way he engaged with the site and with the architecture of the site was so physically responsive to the architecture that I knew that this would be extremely important for doing something at the Horatio Street Gas Station or even in any kind of site specific location.

Having to transpose that piece and do our kind of mini tour, a mini tour of our impromptu ballet troupe to Dia Beacon, made it so that the piece was actually set, the score was set. This was something that I always was a little bit weary of because I didn't necessarily want to have the piece hard set or movements to be hard set, even though some of the dancers really thrived inside of that type of logic of movement to have things really scored and set. The fact that we had to tour it made it so that there had to be a kind of set score, and this created a type of dynamic autonomy in the work which played so interestingly with site specificity, it was fascinating to watch it occur over multiple days.

What happened? To what actually occurred, just in the preparations and the imagination of the work that was sort of floating, it was almost like a filter. The movement, the dancers and the movement was almost like this kind of transparency that was placed on top of the gas station. It was merging but also autonomous. It was emphasized in our rehearsal process because we knew we would have to kind of translate this into an indoor location in Beacon.

Legacy Russell

What is your relationship to the choreography of it all? What did it mean to have two choreographic collaborators within this work? These two different choreographers who participated in the project [Niall and Raymond], they arrived at the mode of collaboration with different stylistic and generational approaches of course as well. As Niall then took the troupe into the world into these two different sites, this became part of the process of instruction and transmission.

Matthew Lutz-Kinoy

This was so fascinating. It was such a huge learning experience for me in terms of modes of communication because when Raymond and Niall were in the room together, they had such diverse ways of explaining movement to the troupe.

Legacy Russell

And that kind of transmission is so important.

Matthew Lutz-Kinoy

The way that Raymond would communicate movement was really not only through it, it was nonverbal. It wasn't self-consciously nonverbal because Raymond really wanted to talk. He was like, I need to transmit this information through movement. This was so fascinating to see his way of resisting language or resisting verbal language and emphasizing the physicality of everything. It was so expressive because through that, so much of this project was about highlighting people's movement languages and kind of bringing the movement language(s) that are held in their body knowledge, and lifting that to the surface. This relationship between expression and movement as this type of language. With Raymond what I was witnessing was something like a nonverbal communication, and then what I was calling Niall as this psychic social worker. Niall’s approach was from what this is, I'm speaking from my perspective on what I saw, was something that really was quite different than that.

It was really a mirroring. Niall was in both languages. In language and in movement he was mirroring the cast's experiences and was trying to hold a mirror to them and show them what he saw they were—what he could see they were as performers and was kind of holding a mirror to their experience. These two very different methodologies and ways of communicating and choreographing the work. I thought, well, who knows? It was present in the final performance that people saw. It was such a gift that the performers gave to me to give us the space to be in the rehearsal room as a witness to that.

Legacy Russell

Having multiple touch points in there, regardless of whether you were inside of the mode of movement versus being inside of the process of holding space, feels immensely valuable. There was a delicate balance there in terms of even just the viewership of that and the act of trust really that was extended. To have that be part of the collaboration was immensely meaningful alongside it, really the various layers of documentation that gave different sight lines into the process, which is a really vulnerable thing to do. The dancers allowed for that to occur, and that kind of record really being something now that is going to be maintained into the future.

Matthew Lutz-Kinoy

I know, and it is so amazing dealing with The Kitchen’s archive in this way—so it's so lucky that our projects met each other.

Angelique Rosales Salgado

Let’s turn to the question of documentation as another kind of witnessing, Matthew. From the jump you expressed a real care for the question of documentation as it relates to not only as a remnant of the performance, but to physical material in the room of the exhibition. Filling Station in the 1950’s was also the first ballet broadcast of television for an American public—so that question of record and diffusion is inherently embedded. Could you talk about your interest in inviting different image makers, Mary Manning, Rob Kulisek, Reto Schmid and Al Foote III to vision different vantage points of documentation for the project. How are you considering the relationships between performance to still image, to moving image, to dancing on film, and how this community is set into the archive?

Matthew Lutz-Kinoy

One of the big cues from observing this historical document of the ballet was so much of this was transmitted through this video, this digitized document of this broadcast ballet, which was done in the moment of the ballet's second release into the world in the fifties. A big meeting point that I had was an interest in performance documentation and our current relationship to a methodological interest in collecting, acquiring and restaging of performance. The possibility that this kind of dialogue could actually have a national United States starting point. Actually, the actual starting point inside this particular piece was so fascinating that actually the broadcasting of this ballet is a kick-starting to institutions and museums being able to collect performance today. That link was something I really wanted to highlight in the entire exhibition and project itself, which was able to be so beautifully manifested inside of other people's creative practices such as Rob, Mary, or Al.

It was another way I got to share the beauty of Filling Station as a historical object and with people who weren't dancers. This project doesn't only touch people interested in physical physical movement. It touches people who are invested in the representation of movement. This link was the depth it provided in terms of a self-referential object that is inside of itself. The video does something where it's the historical document of the video. What we've been able to contribute to that document through our own documentation creates a sort of self-referential bubble that is completely porous and breathes and extends into a public space, the public space of Westbeth and the public space of the city street. It was maybe similar to that. A similar metaphor to that is how I was explaining the transparency of the dance onto the top of the gas station. The documents do something similar where it's almost like you physically layer one image onto the next, in a visual picture plane.

My hat goes off to Dena Yago for pushing me to contact Mary Manning as this person who would be the Walker Evans of our show and do the historical role playing of Walker Evans in our rehearsal room. The cues of the Walker Evans photographs that document the rehearsal spaces of both Belarus and the Ballet Caravan that are found in playbills and in Dance Index were really the key to that collaboration with Mary.

Legacy Russell

That's fantastic, Matthew. How might you imagine this project taking form as it continues to travel? What role does the archive have within its growth over time?

Matthew Lutz-Kinoy

I work so site specifically that I've never had the experience of asking a question like that before. Well, this project itself asks this question, and, Legacy, it is the first question that you asked me, the question of an actual site as a possibility. The idea that this project could exist in another realm. Well, it already does exist in this kind of archive realm—the active archiving of the project to participate in the historical archive and the possibility that this kind of project could be performed in a different way, the performance of this project. The whole project is a kind of active staging. There's this possibility of learning from it—I learned so much in the space of the rehearsal that I feel like there is this possibility to kind of restage this piece in another site. I feel like I owe the work itself to do that because we learned so much in the process of staging it here that it would be a waste not to transmit that knowledge to another group of people or to another institution or to another location.

All of the possibilities of how this work can continue to exist is fascinating to me in all these different formats in dialogue with an archival piece, in a format of a document of what we did at Westbeth. The possibilities of transmitting this information is fascinating. I don't necessarily know or necessarily understand how that takes place, but I definitely know it is possible. I know that there's many forms it could take. It’s like an opening. It's kind of open. This work opens so many doors that it's like choosing your own adventure situation. You have to figure out which door you're going to go through. Now I want to take the project to São Paulo because the Ballet Caravan had a Latin American tour and went to Brazil.

I don't know if this piece was performed inside of their repertoire when they were traveling, but I know that the troupe toured there. I would love to be able to dip into the modern dance archives in Brazil and be able to start to understand why it is such a crazy subject. I talked a lot to Isabel Lewis and to Elizabeth Welch about this—about how dynamic, messy, complicated, and interesting it is to deal with national representation abroad, especially in Brazil for example. How complex and interesting it is to perform an American production or this kind of idea of United States production outside of the United States, then you're talking about real life. It starts to layer how complex it was already to talk about a United States dance movement and what that could mean in terms of contemporary dance. To turn that into an object that then is positioned internationally is deeply complex and fascinating and deals with even more complex perspectives of imperial influence.

Something I talked about with the dancers is the relationship that choreographic movement has to colonialism, and this is something I talked about with the whole cast in the very beginning of our meetings about Filling Station. We talked about the history of choreography as a colonial project and the idea that you can move your body in the way that the people from your country move their bodies simultaneously in the same time period, in the same movement practices as transmitted through print materials and written choreography. This idea is also why it's fascinating to think about how this project could move into other states and other locations.

BIO

Matthew Lutz-Kinoy (he/him, 1984, New York City, New York) lives and works in Paris, France.

Embracing the spirit of collaboration as a means to expand knowledge and skills, the breadth of techniques and references used across Lutz-Kinoy’s practice are the result of many collaborative ventures. Where his ceramics are influenced by working with artists in Europe and Brazil, his large-scale paintings often installed like backdrops, tapestries, wall panels or suspended ceilings assert matters of pleasure, color, intimacy, motion, as fundamental. Lutz-Kinoy’s work looks through a history of representation from the rococo to orientalism to abstract expressionism; challenging what constitutes the inside and the outside of the arts, the social and the self. At the core of Lutz-Kinoy’s practice is performance. Influenced by histories of queer and collaborative practice as well as his background in theatre and choreography, his live work explores the interplay of narratives that are created and constructed between individuals and social spaces.

His recent solo shows include Plate is Bed Plate is Sun Plate is Circle Plate is Cycle, Mennour, Paris (2022), Link Room Project, Cranford Collection, London (2022), Manikin, Mendes Wood DM, São Paulo (2022); Window to the Clouds, Museum Frieder Burda | Salon Berlin, Berlin (2021); Two Hands on Earth, Mendes Wood DM, Brussels (2019);* Sea Spray*, Vleeshal, Middelburg (2018); The Meadow, Le Centre d’édition Contemporaine, Geneva (2018); Southern Garden of the Château Bellevue, Consortium Museum, Dijon (2018); Fooding, Fitzpatrick Gallery, Paris (2018).

His recent performance work includes Soap Bubbles with Jan Vorisek, Art Basel Parcours, Basel (2022), Scalable Skeletal Escalator by Isabel Lewis, Kunsthalle Zurich (2020); Screaming Compost with Jan Vorisek, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zürich (2019); Sharjah Biennial 14: Leaving the Echo Chamber by Isabel Lewis, Sharjah (2019); Rotting Wood, the Dripping Word: Shūji Terayama’s Kegawa no Marii, MoMA PS1, New York (2016).

FUNDING SUPPORT & CREDITS

The Kitchen’s programs are made possible through generous support from annual grants from Bloomberg Philanthropies, Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Howard Gilman Foundation, The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, Mertz Gilmore Foundation, Simons Foundation, Ruth Foundation for the Arts, and Teiger Foundation; and in part by public funds from New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council and New York State Council on the Arts with the support of the Office of the Governor and the New York State Legislature.