Credits:

By Nolan Oswald Dennis, interdisciplinary artist and Zoé Samudzi, writer. Organized by Sienna Fekete, 2021–2022 Curatorial Fellow

July 12, 2022

Exquisite corpse is a surrealist method of collectively creating a text whereby each collaborator adds to the composition by only seeing and responding to what the previous person had written. This generative technique is a stunning metaphor for the assembly of skeletal fragments into a body. Its surrealist ethos coheres a mutable, iterative thinking and working that rejects the arrogant, prefabricated ordering or disjointed “dialogue” that linearity often produces. In the short, experimental attempt at thinking together that appears below, interdisciplinary artist Nolan Oswald Dennis and writer Zoé Samudzi collectively approach what Dennis has termed “a Black consciousness of space” in his artistic practice, referring to the materialities and metaphysics of stolen African artifacts and the lands from which they came. Through a shared Southern African diasporic sensibility, the corpus they begin to form broaches globalities and orientations beyond the nation-state. In line with Dennis’s considerations of “different permutations of the Black globe,” per South African critic Athi Mongezeleli Joja, the text that follows brings together alternative figurations of the earth and [Black] indigenous thought. Samudzi’s words are in italics; Dennis’s words are in bold, with associated diagrams.

Land: Experience, Myth, and Memory

Whether one acknowledges or respects indigenous animist belief or holds fast to the pseudoscience of psychometry, there is a sentience to things. Objects, as well as the terra from which they were extracted, contain their own grammars of meaning that endure even as they are re-spatialized.

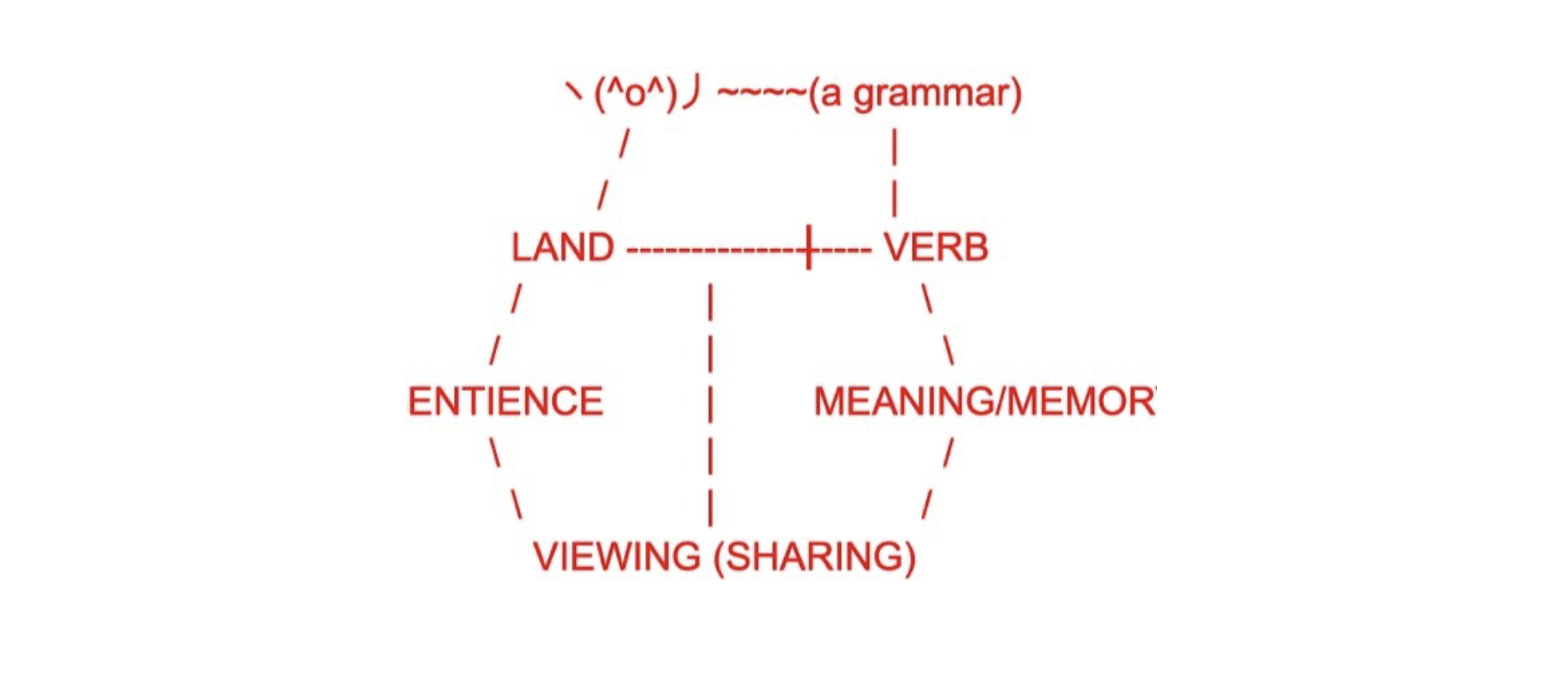

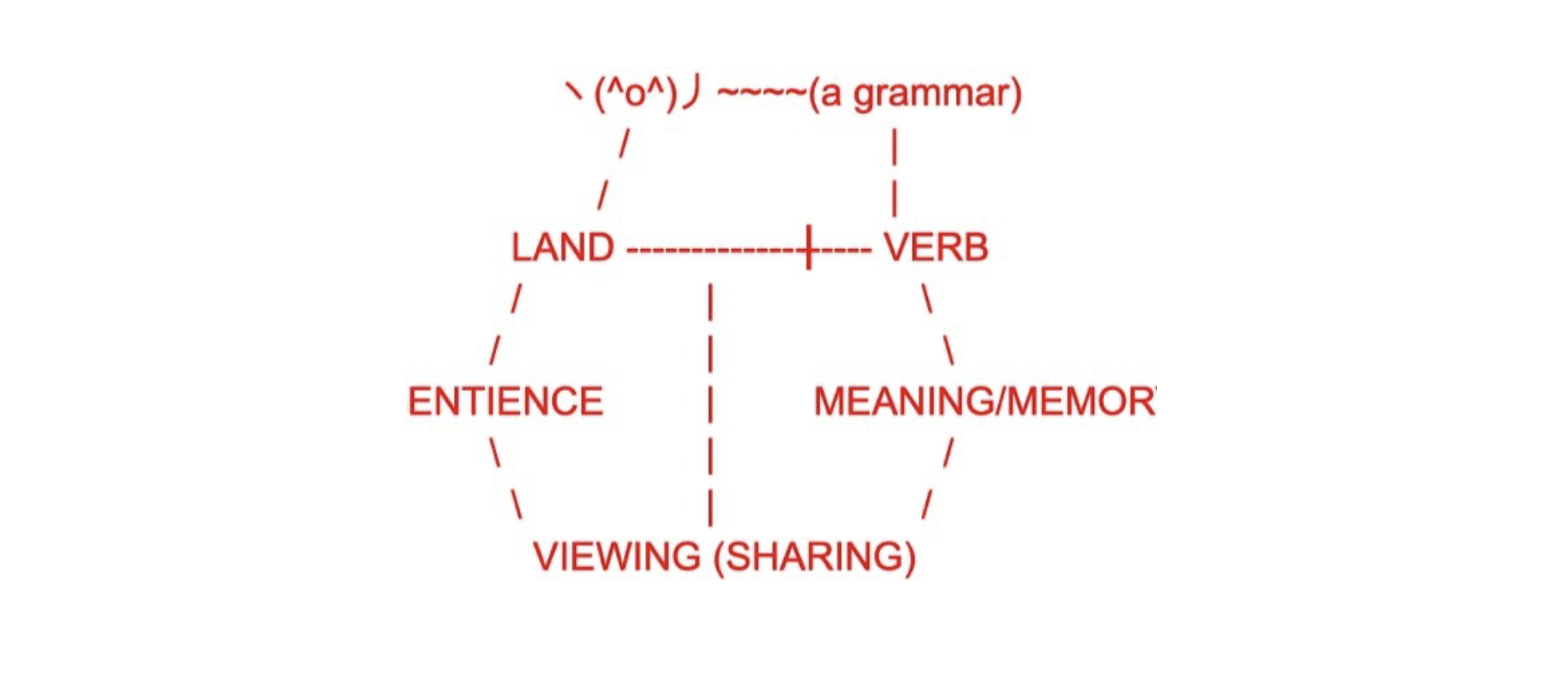

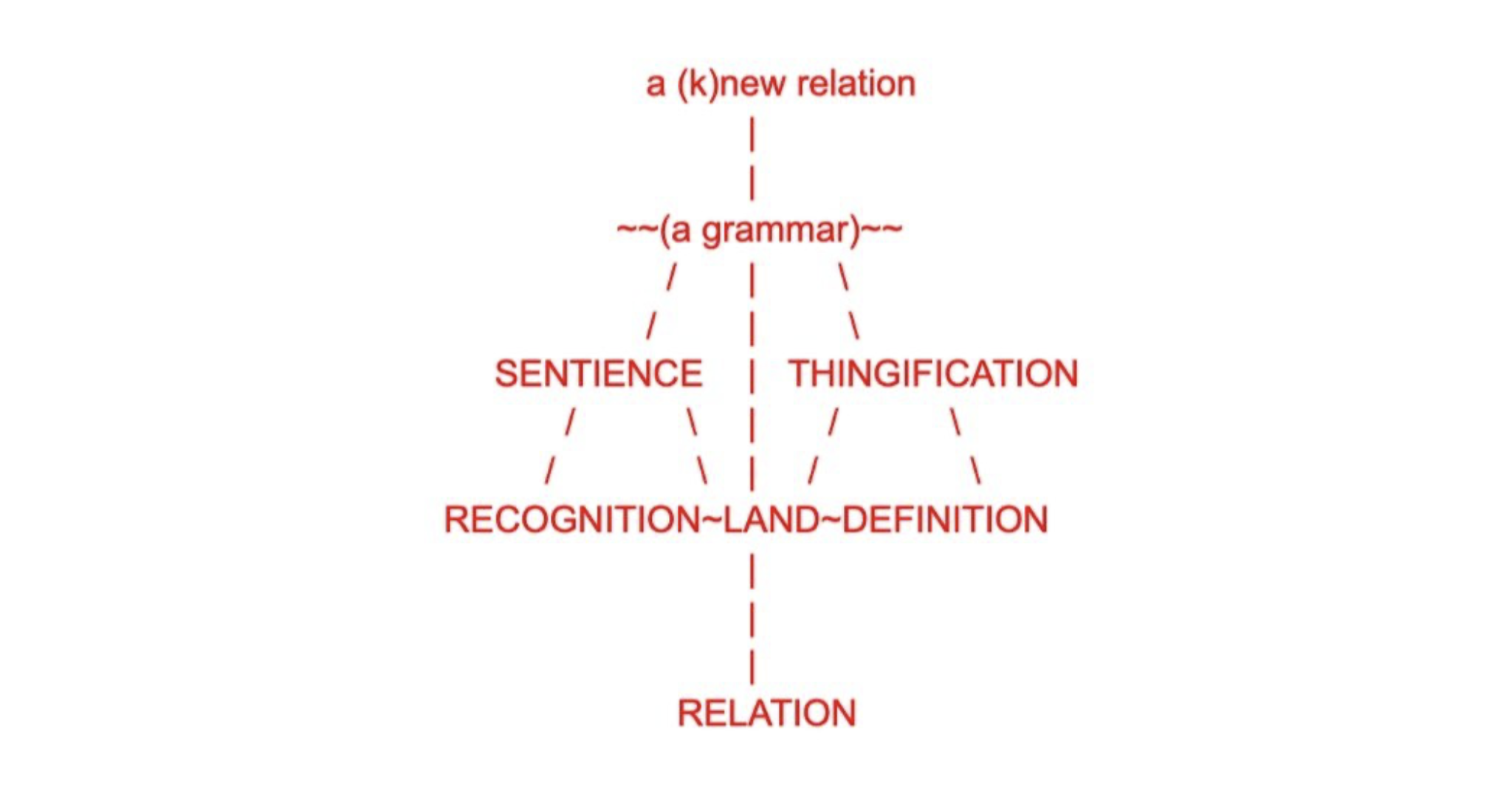

What if we forget about things altogether? I’ve been wrestling with (the implications of) this fragment on grammar from South African photographer Santu Mofokeng: “My approach to landscapes is informed by cleaving the word landscape into its portmanteau component parts: ‘land’ (the verb) and ‘scape’ (to view)....” I’m committed to the idea of “land” (the verb) and the question of what it means to view a verb. It feels like a demand to think of the land as something we do (a collective happening)—a process, procedure, and practice rather than a thing. So maybe sentience is the name we give to what it feels like to watch (view) a transformation in progress? I get the sense that normative (colonial) grammars rely on fixed meanings (and fixing meaning, violently) and presuming objects are distinct from actions. So sentience and agency become a privilege reserved for some approximation of whiteness. But beyond the horizon of that approximation, transformation is the ground of meaning and if everything transforms then everything is a particular locus of meaning (and grammar).

The Land can and often does become like an inert and monumental proper noun in our political imaginary. But as a verb, it is defined by the amalgamation of geological, social-political, and material phenomena occurring on and beneath its surface—capturing processuality and multiplicity that better resist colonial enclosure (and our inadvertent re-enclosure in our honorifics). Maybe a more productive non-imperial grammar is one that does not rest in the ease of counter-narratives that produce other kinds of staticity: ones that capture The Land with inert pre-colonial meaning and mythos that remain vulnerable to hegemonic controls even as they attempt distance from them? The verbed land is what is sentient? Or another word beyond this privileged, Euroempiricist binary of living and non-living?

I like this word: amalgamation. It feels like we need a grammar for thinking about communities of phenomena. The Land is maybe a way to name the partial sum of a set of relations in which geological, ecological, and other chemical interactions are inseparable from spiritual, economic, and other cultural interactions. Land is not simply a territorial proposition but a kind of biochemical-spiritual-political system that is possible in particular ways through particular relations. Enclosure truncates relation, it brings the horizon of possibility so near that the land (as a processual multiplicity) is no longer visible—in Santu’s terms we can no longer “view” the relations we call land. Instead of relations, we are forced to deal with definitions (always in need of policing).

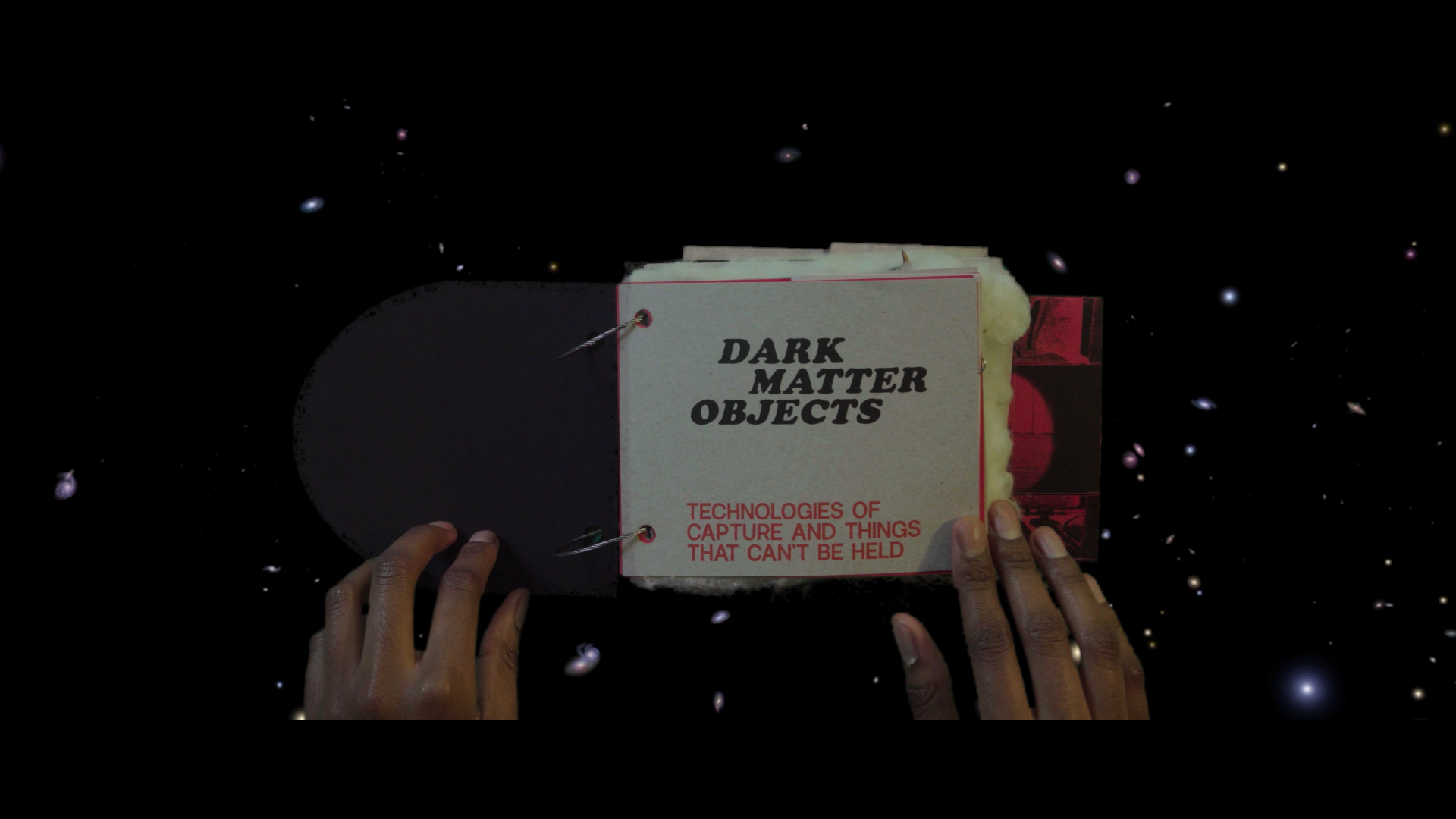

I think the sentience of stolen things is also a way to talk about the pain of recognizing, in an object, a shared longing. When we feel that stolen artifacts (that which is removed) synecdochically represent stolen land (that from which we are removed) maybe what we also feel is the stolen (captured) relation between ourselves and the planet in general. What we need, as part of a non-imperial grammar, is probably a relation in which these categories (sentience, human, non-human, object) are no longer viable. Maybe there’s a (k)new relation where things are not representative but formative and trans-formative?

It feels like communities function as capital R-Relation. I think in order to better begin to comprehend the multiple temporalities of/in/on land, oceanic thinking ironically might be more methodologically useful. Tidalectics permit land[’s biochemical-spiritual-political processes] to inhabit the same fluidity as water. (1) It’s an ecological imaginary of accretion and erosion, nurturing and extraction, etc. that resists the ahistoricism of representational certainties that claim to mark each process’s discrete beginning and end.

Heritage objects are made from earth into which our bodies, primarily made of water, will dissolve and into which our ancestors’ bodies have dissolved. The object made from earth is thus made from spirit and further imbued with metaphysical power and quality both upon its creation and in its capture and subsequent placement into new relational order in the archive. A terrafeminist materiality to Astrida Neimanis’s hydrofeminism. (2) An attempt to translate her ebbing and flowing embodiments into a never-ending unmappable (if we’re resisting border-being) processuality of land containing a transcorporeal ethic. A mutual recognition of person-related-to-thing through this ecology of sentience and shared origin. A responsibility to all sentience of/in/on land complementing the indigenous ways of knowing (ubuntu/hunhu, for example).

This feels like a good starting point.

CONTRIBUTOR BIOS

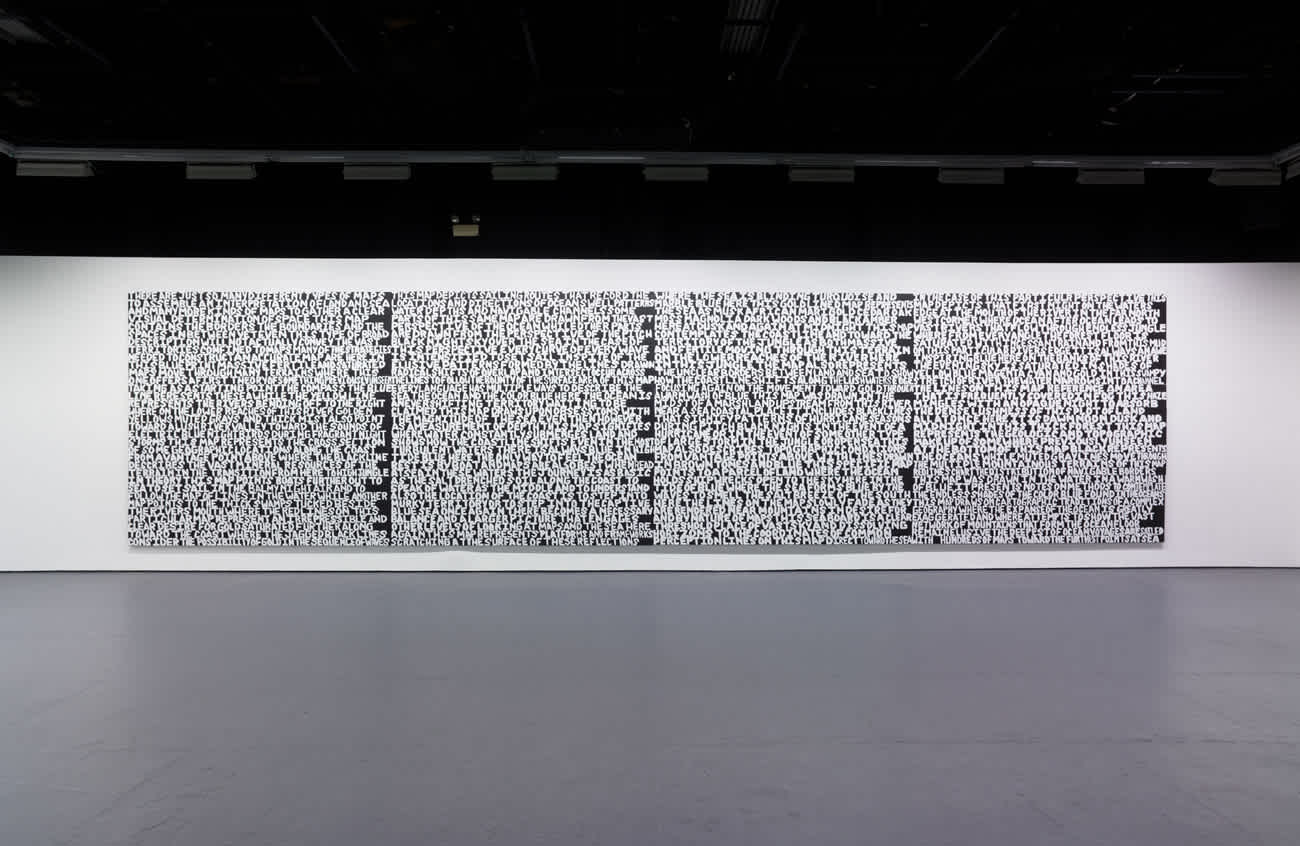

Nolan Oswald Dennis is an artist from Johannesburg, South Africa. Grounded in decolonial politics and working in a non-disciplinary mode, he is interested in the materialization of epistemological difference and the geographies of knowledge. Dennis’s work questions the politics of space (and time) through a system-specific, rather than site-specific approach. Dennis has exhibited in various solo and group shows, including the 9th Berlin Biennale the Young Congo Biennale, Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona (MACBA), and Architekturmuseum der TU München, among others. He was a 2020 artist-in-residence at NTUCCA (Singapore) and a 2021 artist-in-residence at the Delfina Foundation (London).

Zoé Samudzi is an SEI Fellow and Assistant Professor of Photography at the Rhode Island School of Design, as well as a Research Associate at the Center for the Study of Race, Gender & Class at the University of Johannesburg. She is an associate editor for Parapraxis Magazine and was a guest editor for The Funambulist Magazine in 2021. Her writing can be found in Art in America, Foam Magazine, The Architectural Review, Artforum, ArtThrob, The New Republic, and elsewhere.

Footnotes: (1) Coined by Barbadian poet and historian Kamau Brathwaite, the theory of tidalectics invokes “the movement of the water backwards and forwards as a kind of cyclic…motion, rather than linear.” Contra to the rigid oppositional binaries of dialectics, tidalectics allows for a constancy of multi-directional movement and fluctuation and the hybridizations that occur throughout. Kamau Brathwaite, ConVERSations with Nathaniel Mackey (Staten Island, NY: We Press, 1999), 44. (2) Hydrofeminism considers the intimacies between embodiment and the overwhelmingly water-based composition of our bodies. We are not discrete individuals as Enlightenment phenomenology would have us believe. Rather, as “bodies of water we leak and seethe, our borders always vulnerable to rupture and renegotiation,” as Astrida Neimanis notes in Bodies of Water: Posthuman Feminist Phenomenology. We are inextricably linked to, comprised of, and enmeshed within the waterways of a “more-than-human hydrocommons.” Neimanis is not the sole theorist of feminist conception of embodiment, but her text is formative nevertheless. Astrida Neimanis, Bodies of Water: Posthuman Feminist Phenomenology (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017).