Credits:

Ava Goldwyn, Winter/Spring 2019 Curatorial Intern

September 20, 2019

The Kitchen has a history of acting as a hotbed for artistic experimentation: it has staged early exhibitions of numerous artists who later went on to gain prominence. One such artist is John Miller, who is best known as a visual artist and critic and whose artwork is distinguished by a sometimes tongue-in-cheek critique of society and by a subversion of the boundaries between media. Miller’s first exhibition at The Kitchen, Recent Work, opened in April 1983. It was his second solo exhibition as a young visual artist and recent graduate of CalArts and the Whitney Independent Study Program. Since then, Miller’s works have been incorporated into the permanent collections of the Whitney Museum of American Art; MoMA; the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami; the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam; and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (among others).

Miller has returned to The Kitchen several times since his debut exhibition to perform as a musician, including in 2009 as the guitar player for the experimental band XXX Macarena with Jutta Koether and Tony Conrad. The performance took the shape of an entirely improvised, noise-based soundscape, in anticipation of the release of their first record XXX Macarena (2010). A few years later in 2013, Miller returned with another band, The Cornichons, to perform as part of Olivier Mosset’s exhibition Exposition de groupe. The Cornichons, which features Servane Mary, Aura Rosenberg, Jose Martos, and Dan Walworth, is a global country band that has performed at international venues, including the 2015 Venice Biennale.

Miller’s cross-media artistic practice is emblematic of the diverse creative outputs that The Kitchen regularly supports. Looking back at his career, John Miller shared with us his thoughts on his double life as an artist-musician and offered his perspective on multidisciplinary experimentation.

ON HIS VISUAL ART PRACTICE

How did you get started as a visual artist in New York City?

After getting out of school, I had been working in video for a while, but I was moving toward using video more cinematically. Then, I went from video to artists’ books. I hadn’t seen the actual drawings that Raymond Roussel had included in his book Impressions of Africa (1910), but his idea really intrigued me. Roussel had hired an artist, Henri Zo, to produce drawings for the book based on descriptions, so they weren’t illustrating anything actually in the book; the drawings were like their own narrative component that ran on a parallel track to the text. That idea brought me back to drawing.

I made these quick ink drawings for one of my own books. I wanted to see if I could show them at The Drawing Center, so I made an appointment to have a portfolio review. I met Tom Lawson for the first time, who was then showing at Metro Pictures [and acting as a curatorial consultant for The Drawing Center]—now he’s the dean of CalArts. He took one look at my drawings and said, “I’m sorry my colleagues aren’t going to accept this work, but when you feel ready, I’d be happy to recommend you to my dealers.” He did later recommend me to Metro Pictures, who I have continued to work with to this day, but, before that happened, I ended up having a show at Artists Space. Once I was in that show, I was in this whole network of alternative spaces. In short order, I had a show up at Hallwalls in Buffalo, a show at White Columns, and then one at The Kitchen. At that point at The Kitchen, Howard Halle was the curator. He was super supportive, even bought some of my work early on. I had very little money, but he didn’t have much more than me. It was really fun doing the show with him.

Thinking back to some of your early works like those you showed at The Kitchen and your brown impasto pieces, what were your sources of inspiration?

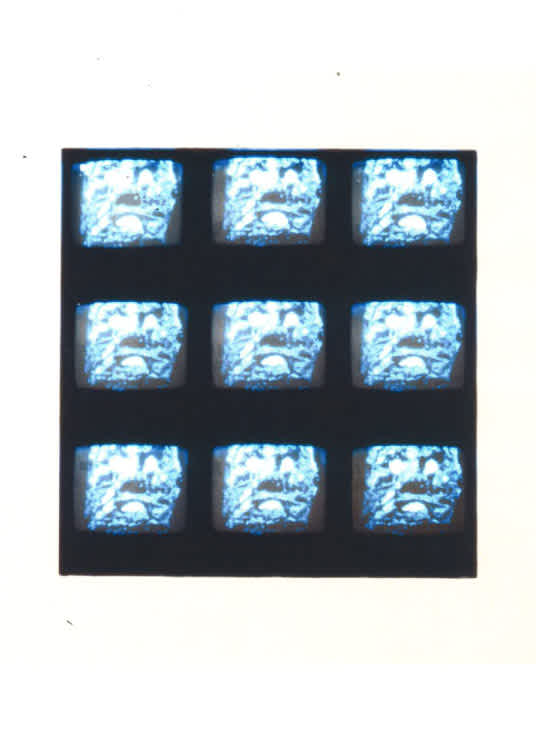

At the time, David Salle was an extremely influential artist in New York. One of the tropes of his work was to use a diptych format to produce these very plain paintings of three seemingly discontinuous elements, like a nude female model, a telephone, and a car crash. I felt like it was presenting viewers with a fake, avant-gardeistic dichotomy. I thought it would be interesting to instead collapse all of that back onto a normative picture: I wanted to provide a scene that would seem overly familiar. What would then be difficult for the viewer of my scenario would be the absence of a contradiction. I was producing drawings and paintings by imagining what the proverbial man or woman on the street considered an ordinary picture. I thought of them as being pictures of pictures and thus having something to do with ideology. That’s what most of my work in The Kitchen was. I produced also this weirdly early brown piece. It was a crude head on a wooden box with plaster over it and two eye holes, which I put on a strobe light and mounted in the space. I also did something where I had a little monitor that flashed an image of the [brown] piece as a grid of nine heads in the space.

What precipitated my brown impasto works was this regimen I had set up, where I was trying to paint a painting a day; this was when I was doing those pictures of pictures paintings. I went through a certain arc in the process, where I started off slow, hit my stride, and then was starting to burn out. Toward the end, a painting would take a week, which seemed incredibly long.

Through the process, I started equating paint with luminosity. I was kind of influenced by William Blake: you apply layers of translucent colors and you build up this luminous effect. But then I started to have the opposite feelings towards paint. I thought: “What if it’s a substance that’s sealing off the surface of the canvas, instead of creating luminosity, which is uplifting? What if it’s a sense of repression?” What got me into those brown pieces was this emotional state of being that I worked from associatively.

I actually started off doing brown abstract paintings. They would look really good when they were wet, but then after a week, the paint would dry and flatten out. The part that I liked, the impasto, wasn’t there, so I incorporated modeling paste into the acrylic, because that keeps its volume. I really never worked with oil painting. I was taking a kind of counter-Arte Povera position. I thought it would be more interesting to use synthetic materials and have those elicit a visceral response. Through the choice of materials, I could point to the constructed nature. That was one virtue of having to use modeling paste—because it meant that I was constructing a stroke. So yeah, I was jumping around media-wise. Of course there were other artists doing that at the time too, but it was a little more exceptional. Now, it’s become much more the norm.

ON MUSIC

Let’s talk about your music. In 2009, XXX Macarena performed at The Kitchen. Could you tell us about how this group came about?

XXX Macarena came about through Karin Schneider, a Brazilian artist who is one of the founding members of the artists’ cooperative Orchard Gallery. Karin was doing a piece at Orchard called Sabotage (2005), where she set up a smoke machine and filled the gallery with smoke so you couldn’t see the other works. She was telling me about it, and I said, “oh, it’s like a metal show.” Then she said, “oh do you want to play music?” For that first show, I didn’t want to play, but Jutta [Koether] played. Jutta had been playing noise music for a while; she had a band with Steve Parrino here in New York for many years. Karin went on to do Sabotage at the Sculpture Center [in 2006] and she invited me again to play with Jutta. I decided that I would, and I played guitar with a slide so that I could have sustained notes, which I put through a heavy effects unit. Jutta and I really clicked, so I decided we should do it again.

I was having a double gallery show with Friedrich Petzel and Metro Pictures, and I knew that Mike Kelley was going to be in town, so I invited Mike to play with Jutta and me. I’d played with him at CalArts, in a band called The Poetics. He knew Jutta and me well, so he said sure and that we should invite Tony Conrad too. At that point, I was unaware that Tony even made music. Tony was, as it turns out, one of the founders of minimal music: I had only known his film work. He played violin or instruments he made himself and also used a lot of effects loops. Jutta played synth. The exhibition space of Petzel was really small and people crowded in, but it was fantastic. That night I was showing my gold work, so Jutta was wearing a gold mask and a gold lamé suit, but Mike had this whole thing where—and he was just a masterful performer—he was drumming on different surfaces. Tony and I were recalling the performance once, and he said “as you recall Mike was drumming on me too.” That made the performance different, because it was closer to an art performance in some ways—totally unscripted, everything was improvised. Jutta, Tony, and I kept playing together, and we played at The Kitchen one time.

I played another time at The Kitchen as The Cornichons, when Olivier Mosset had a show there. Olivier lives much of the time in the Southwest, so he brought a lot of Southwestern musicians to The Kitchen, but we played too one night. He also had Arto Lindsay play as part of the program, which was amazing. I’d seen Arto Lindsay back in the day, when he had DNA—the no wave band. He doesn’t tune his guitar or play conventional cords or anything, so that of course was totally in sync with no wave.

ON ART-MEETS-MUSIC

How does your work as a musician appear in your visual arts practice?

The new mannequin videos I’m doing relate in some ways to minimal music and a lot of my work with Takuji Kogo is music based. I started collaborating with Takuji years ago. Matt Keegan invited Takuji and me to do a show right after 9/11 in this company called Global Consulting, whose offices were very near to the World Trade Center site. At the time, their offices were very empty and there were all these vacated cubicles. A friend of mine proposed to do a show there with the office manager. What I did was take photos of the cubicles and superimpose personal ads from the same zip code as Global Consulting onto the photos. Then Takuji took all the ads and turned them into a song, a kind of medley, which was funny. After that show, I said we should try to write the best songs we can using ads as lyrics, so we’ve done that for many years now. We have a YouTube channel. Our virtual band is called Robot. We do everything synthetically, even the voices—we use a text-to-singing software.

ON THE FUTURE

You have experimented with so many media throughout your career. Where do you see your work going next?

Postminimalism and augmented reality—those are things that I am curious about. One artist I think about is Jordan Wolfson because he has used high-tech media like robots that can respond to viewers. I do have a tech geek side and I like to play with things. But for right now, I’m pretty much focused on video. Part of the way my videos are working is just learning the capabilities of Adobe Premiere and After Effects. As I discover something new, I decide if it can be a piece. That’s kind of how it’s working. I’m fearing that when I actually have a real handle on this stuff, the ideas will dry up.