Credits:

Sheryl Sutton, Elliot Reed

November 26, 2024

In conjunction with artist and performer Sheryl Sutton's solo exhibition The Kitchen in Focus at 47 Canal, artist Elliot Reed joined Sutton for a conversation about process, performance, archives, and collaboration, reflecting on her career and pioneering work at The Kitchen in the 1970's and 1980's.

The conversation took place on October 24, 2024.

Elliot Reed: I'm super excited to be here. I already told you this over the phone and email that I've been a huge fan of your work, but only through media, your photographs, through videos and everything. So when this opportunity came up, I was so excited that The Kitchen asked me to be a part of this, so thank you. I'll start with that and before we kind of go a bit more extemporaneous with it, I would like you to tell us about your solo [exhibition] that's on view in the other room? I think a lot of people know you from your work with Bob Wilson, but not so much about your own.

Sheryl Sutton: So this solo came about, first of all… it was a really long time ago. I'm not going to be specific because I don't remember it frankly. It was one of the first solos I made and I was so impressed with the fact that I had imbibed a vocabulary from the people I grew up with dancing with Bob Wilson. So our work initially was to dance in a space free dancing. Even though we weren't interested in learning steps, or acquiring a technique, we acquired a technique and it was us, how to see us, how to move, how to learn about movement, how to be free in your movement. I'd studied ballet as a child, 12 years of it, and when I met Bob Wilson at the University of Iowa, I said, “This is what I want to do. This is what I've been looking for.” I was sure that there was an art based theater, okay, it's not Broadway.

“I don't have to do that,” and that's what they were doing at Iowa. So then I ended up with these crazy people in a room and they were all free and moving and doing and inventing, and that's really where all of the solo making came from. So my solo was really to copy these movements, to copy how we've learned to move, how we've studied movement. I wanted to show, yes, we do have a shared vocabulary and we've acquired it vicariously from being in the same room from doing this work, not really with the point of making choreography, but in fact it became choreography for a lot of people.

ER: I think what was super exciting to me about the first time I encountered you as a mover was just your completely punishing, all encompassing severity and just gorgeous precision that as a mover myself was just so magnetic and attractive. It's the way that you're able to completely slice through many boundaries of affect and perhaps joy, but I mean, yeah, in the best possible way. I guess we had talked about this a little bit before, but can you tell me specifically beyond just the time that you had improvised with Bob's other performers, what qualities do you feel like you were able to cultivate within yourself that you used in these solos, but also later on in Bob's work?

SS: Well, there was a lot of emphasis on slow motion and the cell of the performance I made initially was about slow motion. I was really studying how to be water and that interested me, that interconnectedness of the body and Bob's whole point of view was that the dance is the premise on which we make our theater. At the time he was thinking about everything. For him, it grew out of the body and the body is a series of circles and connectives. Because he was so interested in simplicity or oneness (you could say doing one thing), that's how I ended up always in front of everybody performing the activities he wanted. He wanted it very slow and he wanted to learn. He wanted everybody to learn the connections I had made with movement and it was all about slow motion. For me, the image I held was that it has to flow.

SS: If it flows like water, then we're getting to the point of somehow everything being connected in the body. If you can find the circles and direction of those connections, then you can make it important. Even the smallest things. So I had activities like peeling the onion, pouring a pitch of water endlessly just crossing the room and he'd say “Cross the room,” and so I would cross the room and it would take 15 minutes to cross the room and I would say, “Well, this is boring, but this is an activity.” What is the activity about? It's about doing one thing. The hardest thing for most actors or performers is to do one thing. Of course he didn't like psychology, so it was important to find a reason to do what you were told to do for yourself, whatever it was, but don't project it. Everything was inside your information, your attitude.

The presentation itself was inside of Bob Wilson's stage. Everyone kept their eyes at a 45 degree angle. So there was no presentation. No show business, I'm not out there, I'm here and you can look at me. This is very strong, it's very powerful. I think he got that from 17th century painting because he was a painter and he wanted his stage to be painting. He wanted it circumspect. We don't present the material, you come to the material. What that does is it doesn't interrupt what he's doing, which is painting with light. So he's telling you what to watch and what's important and what he feels about what he's made. It isn't very free in fact, but it's the most free because you can choose to go along with it or not. I made solos that really reflected the techniques I learned from his theater and those techniques were to internalize the activity to make it yours somehow, to find a subtext the way actors do.

What is it about? What does it mean? What's important and make that important for yourself? He always said “Sheryl has so many stories in her head,” and I did have stories, and when I made solos, I said, “I want to show what dancers are thinking about when they're dancing and they're counting and they're doing and one and two and three and four,” …I had lunch last night and now I'm going to go here and did I do this or that? Did I turn off the stove and where's my whatever, so that your life goes on in your head even while you're fulfilling the requirements of the choreography. I said, this is a rich life. Dancers are still alive. So all of those things were sources of why I made that solo.

ER: Yeah, I think part of what you're describing or what's interesting to me, is just acknowledging how much of performance or the theater of performance is actually a farce. So even though I encounter your work with a level of words I used before around severity and precision and all these things, which are true when you think about how at its core you're kind of taking things from the past to present and sort of just simplifying them. The irony is that just by bringing things down to their core and taking them to a new context, that actually the essence,, the essence of the thing, the essence almost feels more alien than “Who am I, whose brother am I in this scene? Or where's this story?” That's just a gift of this contemporary mode of working. From that, I want to transition to questions about authorship because something I'm really interested in seeing you through video, through photo for so many years and then now and knowing you some in person, how does it feel to have your complete autonomy as a mover for your own solos, but also being such a core part of workshopping new pieces?

I guess I'll drop the word muse into the conversation as well, which I’m hesitant to do, but oh, not at all.

SS: Tell me about it. It's very unique being someone's muse. You were the source of their artistic endeavor. Unbeknownst quite often, I always decided that at some point—this is when I looked like a 14-year-old boy—that Bob Wilson must've had a great lover at that age and they resembled me. And so his love for me was a translation of that expression, and I didn't mind the way I looked at the time and it was so ambiguous to be both male and female. The whole city of Paris was asking, is it a boy or a girl? I thought, wow, that's fantastic to be so anonymous and so unrecognizable and yet be famous. Andy Warhol said, everyone will be famous for 15 minutes in the future. And I said, I'm going to hold out. Nobody's going to know me and my 15 minutes, it’s going to be real late, it's going to be long time from that. So I thought, yeah, it's a way of hiding. I tell people I was trying not to have a career for 40 years, and I pretty much arrived at that.

It is a way of subjugating yourself for the material and the material is always not more important because the longevity, the eternity of it is in the art form, in the expression and the theater is so ephemeral, it doesn't live forever, but film goes on. We have people, it's so wonderful to have Audrey Hepburn when she was 20 years old. This is a great beauty and it's still there. It's alive. We can look at it. We've got the Turner Classic Movies, and you can see these people in their youth when they were the most gorgeous. I think, yeah, that's eternity. We've overcome that barrier. Life does have a beginning, middle, and end, but it doesn't have to and that's wonderful. That's so fantastic. So that's who that character was. I don't have any qualms about the fact that I, Sheryl Sutton, is anonymous behind the works of Robert Wilson. Robert Wilson's work will live forever and so will Sheryl Sutton, and I didn't have to do that. So I'm really grateful for that whole relationship. I think that's a remarkable thing that we've actually overcome the limitation of life in that with film, it's there forever with photo, forever.

I still meet people in Paris who say, Bob Wilson's show Deafman Glance changed my life, and I think that's remarkable. Isn't that incredible? It wasn’t even in French, and we still did that with it. So there are no limits to what you do. You never know the importance of what it is you're doing. You should always make it important for you and do it, and then other people are going to provide that significance. Now, it's not about fame or something. People do fame now on the internet and they don't do anything. They just cook or something. They're cooking and they're getting famous and they talk about this tomato and I have to cut it this way, that's also there forever. They don't even see it that way. They're just for the people that subscribe to it.

ER: They need help with their tomatoes. Speaking of the film, how does it feel to watch yourself in Deafman Glance now? You told me that this version that's on view here is the one from PBS.

SS: How does it feel? Well, it's somebody else. It is not me. I don't look like that now and I don't have all those connectives that I had once. The connection to the material and the importance when we did that sequence of the murder, I could relate to it then. I just arrived at the University of Iowa and they needed a black actress to do Madea. So I did Madea and the whole myth of a murderous mother who kills her children had nothing to do with that. This is a woman in a room and she kills these two children. So un-murder like, right, it is a ceremony. It's a procedure. It's about the slow motion, the trance that it puts you in while watching. She does these gestures and you're obliged by this Wilson timing. He says, “it's like watching a cloud and you're watching, and she's doing these most violent things.”

She's killing these children, but oh my God, it's as slow as it can possibly be. It's trance is a way for you to slow down and be taken, be absorbed. So I don't have all of that connection to it now. To me, it's a character of personage on tape, on film, and it was an important role at the time, but I did so many since then that I wouldn't say that's the most important role. A lot of people would say, yeah, it's that slow motion that is the quintessential gift of Robert Wilson. Besides his lighting, of course, I don't think he even uses slow motion anymore. He doesn't have that preoccupation. He's moved on. People move normally and really on his stage these days. But it was fun seeing a lot of really fantastic opera singers because he always makes you have space around your arms and seeing them both having to make these positions when they had to sing operas and finally in time, understand that when you are standing like this, even to sing an opera we can hear you better because we can see you better. His whole thing was putting light around the entire body, and he was painting with light, and that's what made people appreciate even those awkward positions. So I think everything comes in time. You understand the significance and importance. Did I get off the subject there?

ER: No. No.

SS: Okay.

ER: No, but I did, my question is changing right now. I really love this notion of painting with light. You're talking about in your solos when you're doing a lot of work where you were speaking of in addition to moving, you're trying to find a way to bring the interiority of the dancer out to this stage.

SS: That's a great sentence right there.

ER: Exactly. I would never have come to that. Thank you. Do you ever consider volumes? I guess there's the auditory volume, but more so in a spatial sense. Obviously as a trained dancer-actor, that's a preoccupation, but on a deeper level in the studio or in your work with other people, how do you feel like volumes kind of influenced the way that you move?

SS: Volumes? Well, because I was so constrained by the requirements of the Wilson stage, I experienced all of those lower intensities much more than other things. We did do shows in which there were roles that require the kind of outward, open, grandiose kind of mentality. Those are just amplified versions of the internalization of making things fluid and small, you could say.

Did I understand your point? I think, yes, it's intensity. Any actor or dancer gets used to something because they have to do it all the time, and then it changes and it goes to somebody else and it's different. It has to be bigger or it has to be broader. It has to be louder. All of those differences are attainable. You have to try them out and see what works. When I made solos that weren't directly related to talking and improvisation, I made solos that had rap music. I did one in Germany that missed that. When was that? Yeah, don't ask. We'll have to ask Carol. Carol remembers all the dates. So it had rap music in it, and that was just to juxtapose my choreography to what was going on now. I didn't have anything to do with rap music, but I liked what I heard and I thought, yeah, I can use this and how can I use it? I used it rhythmically, repetitively, and it was a way of exploring something new and different. That's all. I could accomplish that too, because it was interesting. I did it in my sort of internalized way. Anybody else it would've been big and gigantic. I never could do that really, but…

ER: Perfect. Okay. Tell us about the Byrd loft.

SS: We had the Byrd loft that was on 47th., Spring Street and was three floors. The ground floor was a dance space and the elongated loft and we had open dancing. The open dancing when I was there most of the time was on Friday night. Anybody could come. It was just with music, without music, any kind, pop, jazz, classic music, people moving. This is how we prepped our training for the stage for Wilson's theater by moving and learning to move and studying, moving. Everybody had their own agenda and sometimes it was fun and just bopping around. Other times it was very serious and there were all kinds of dancers there. So you could learn from all of these dancers because they were in front of you. You could ignore them too if you wanted to. But there was a way of exchange and seeing new things, of coming to new conclusions. I always felt like free dancing requires years of doing. If you go and take a class at the Ailey School, you'll get to it much faster. The Ailey School is going to teach you about the port a bras, but it’s going to teach you about a modern port a bras.

Anyway, you're going to learn steps, you're going to learn things about your physiology that works. But you could come on that on your own. You could teach it to yourself. It might take years. And that's why we danced. Every time we prepped for a show, we danced. We got in space and we moved and we exchanged. We provided material for each other in a way. So this was a laboratory space. The ground floor was the performance space, rehearsal space. The second floor was the office. The third floor was a workshop space. I think above that was an apartment. When I came from the University of Iowa, I went to work, I was paid $25 a week, and I sewed animal costumes. So some had bunches of animals on them, gorillas, bears, all kinds of animals. We had this fake fur stuff.

And if you know Soho, the past… Soho had been serious as a sweatshop. So there were these big industrial sewing machines. They left them out on the street. So we took a couple of them, we brought then to the third floor, and we sewed the animal costumes for the show in that space. And then we rehearsed on the first floor and had meals. Andy deGroat, who was Bob's choreographer at the time of Deafman Glance and to the first production of Einstein on the Beach, made dinner for everybody on the first floor or in the basement. I can't remember the second floor, but we would eat a meal together every day.

ER: And Jim and Bob, I can't imagine Bob being a very good cook. I don’t know, maybe he is, was he? I think Bob, probably was good at everything.

Audience: He did make spaghetti with hot dogs and it was…

ER: You said you were living in the building too?

SS: It was a very functional building and it was the groundwork for the Byrd school. Yeah. What is the Byrd school? The Byrd school was the group of people that worked with him at the time. There were people from Soho, and there were ladies from Short Hills, New Jersey. They were supportive of his work and they wanted to participate in the shows. There were dancers and actors and painters and musicians and friends, and they were so supportive of his work that they made. The theater happened at the time. One of the shows had been done already. He'd done other things, of course, and it was a jumping off place. There was a performance space, but it was much too small for the majority of the shows. But we did a lot of rehearsing there. The Byrd school is not really in existence anymore. Now there's the Watermill Center, the center he has in East Hampton for invited guests and students.

ER: And a lot of chairs.

SS: His chair collection is huge. Yes. He also makes chairs and people come there to work with him to learn about lighting and performance. Because he's done so much all around the world, it's a multi international conglomerate and it's a way for a lot of young people to begin and start their own journey in theater, dance, music, whatever.

ER: So I'm going to jump a little bit to the early 2000’s. Can you tell me about your work with Hilton Als, because he wrote to play for you or about you?

SS: I didn’t work with him at all, but he just wrote a play about me, and it was the bird woman. The bird woman is that character, the murderous mother. He had the dress, he got the dress from Bob Wilson, and he did a whole exhibition about that particular character. I think what he was interested in was the significance of being a Black actress in avant-garde theater. In the early days, there weren’t very many of us, and I don't want to say this—me and Ellen Stewart—there's a lot more people that maybe are just there but we don't know about. I was significant in that I was there in the early days and there weren't very many Black actresses. The way it happened was at the University of Iowa. I was recruited by the admissions office who on the auspices of the football and basketball players who were insisting that he recruit more Black women. So he went to Chicago where I went to high school and specifically to a Black high school and recruited a number of Black actresses, or not actresses, but Black women who wanted to go and study at the University of Iowa.

ER: I mean, I guess there's no other way that they could do it, but that's so psychotic.

SS: We got imported here. So it goes on, they complained. Those men were on the campus and they were imported to play basketball and football. And they complained that, well, “we can't date anybody.” There are no Black women here. So he recruited five women, three of which studied nursing. One was a social worker and me as the only other. So I had 21 dates the first week, and I had breakfast every day by saying, I'm not going to sleep with you. And they said, yes, ma'am. Okay. You know how football players are? No, all the dates were like that, but that was the end of it.

ER: So after being imported to the University of Iowa from Chicago, you also were shipped off to New York shortly after because you said that after getting cast, Bob Wilson was there at the university just workshopping in peace.

SS: And that was Deafman Glance.

ER: And then you basically got the job right from school.

SS: I didn't believe it. He said, we're doing this show in New York City and you should come and work with us. And that's why I went to New York to work on it, and I sewed animal costumes by day and rehearsed the work by the night.

We were mostly at the 92nd Street Y. The majority of the people were not dancers or actors, but friends and people who really were encouraged by his work. So that's what I did in the beginning. Then I went back to Iowa for a while and eventually ended up in France and in Germany and lived there. It turned out that Wilson's work functioned extraordinarily in France. There was also major interest in Germany. So in the eighties I moved to Germany and did 15 or 20 shows in the German theater system. The reason is, of course, that Bob’s lighting rehearsals were three weeks instead of three or four hours. He could not survive in the theater program here in America because the unions don't allow 10 hours a day for three weeks to do lighting. But, that was possible in the eighties in the German theater system because they didn't have unions. Everyone has a contract for the season. So we would rehearse and he would do his lighting, painting over weeks. That’s how you get that kind of precision.

ER: And you heard it here first, cancel unions. [Laughter]. Kidding. No. Me neither. But no, it's a real thing. It’s sort of a different kind of, it's not what I think is…

SS: [Laughter]. Good because unions are jobs for people and people need jobs. The problem is, you can't have 10 hours of lighting rehearsals.

ER: Or you just need an exorbitant budget where you can just…

SS: Pay people. Exactly. So that's why he has to work in the opera, The Met here and Los Angeles and Houston, because they have those kinds of budgets. You can light there even weeks at a time.

ER: That is crazy. Even two days of lighting, I start to think it’s too much. How are we on time? Do we have some questions? Anybody?

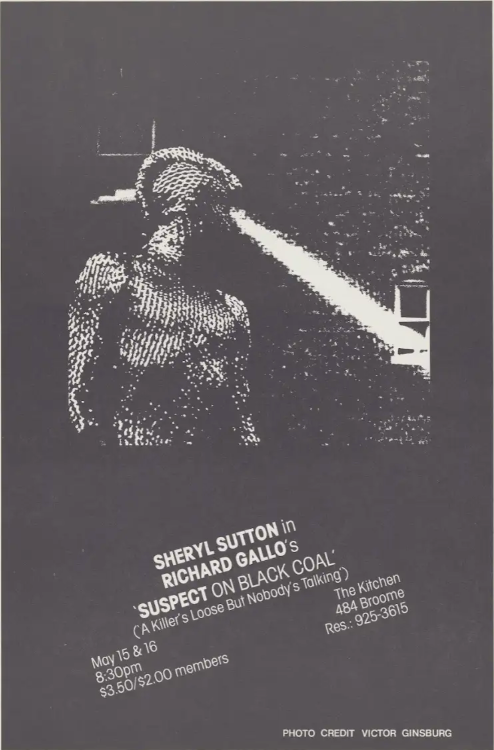

Audience: Yes. What about Richie Gallo? I mean, there's a whole bunch of stuff in there and I'd like to hear something about him.

SS: I worked with Richie at The Kitchen. It's because they asked him to do something. He used to do that crazy street performance. Richie Gallo was the first spaceman. I loved him. He was completely unconventional. He was a bodybuilder. He was beautiful. He was a muscle man. And his boyfriend made wonderful costumes for him. He was like the first Marvel hero. And all of those clothes, the Matrix black leather costumes, coats down to the floor. That was Richie Gallo. He did a great show called Lemon Boy on the steps of the Central Library where he dumps a thousand lemons down those steps. And he stood—he was statuary in what he did in his performance. He would stand in various positions, poses, and this character that he personified was radiated just by looking at him. There were no storylines. There was only the image. The minute you saw 10,000 lemons on the stairway at 42nd Street and Richie standing statuary, you understood what was going on. So we started like that. And then I did the piece within here. I had a bunch of texts to learn. I can't for the life of me remember to this day what it was about. It was important for Richie. I learned the text and I had a crazy costume and I was laying on a swing, and there were images of animal carcasses and animal sounds in the space. Richie was a real street person. He was a resident of the anvil.

Oh, the club and club. Yes. And he took a lot of drugs. He took ketamine. We would go to Studio 54, usually between two and four in the morning. And I would dance, and Richie would be a statue and he would have this wine, and he would stand and I'd be jigging all over the place. Then the place would be empty because it was four in the morning. And that was Richie's thing. He wanted to be seen. He didn't want to do anything. He was good at it. He was really good at it. So he'd wear this long leather coat and high fisherman boots and the mask that just went around his eyes. And he stood for 15 or 20 minutes and I'd boogie all over the place. The music would be disco music. At a given moment when the music was particularly important, he'd reach into his fishing boot and take out a bread knife. I don’t how we didn't get thrown out of there, but we did it. And they loved it. People loved it. And that's what we did first. Then when The Kitchen asked him to do this piece, we made an actual performance.

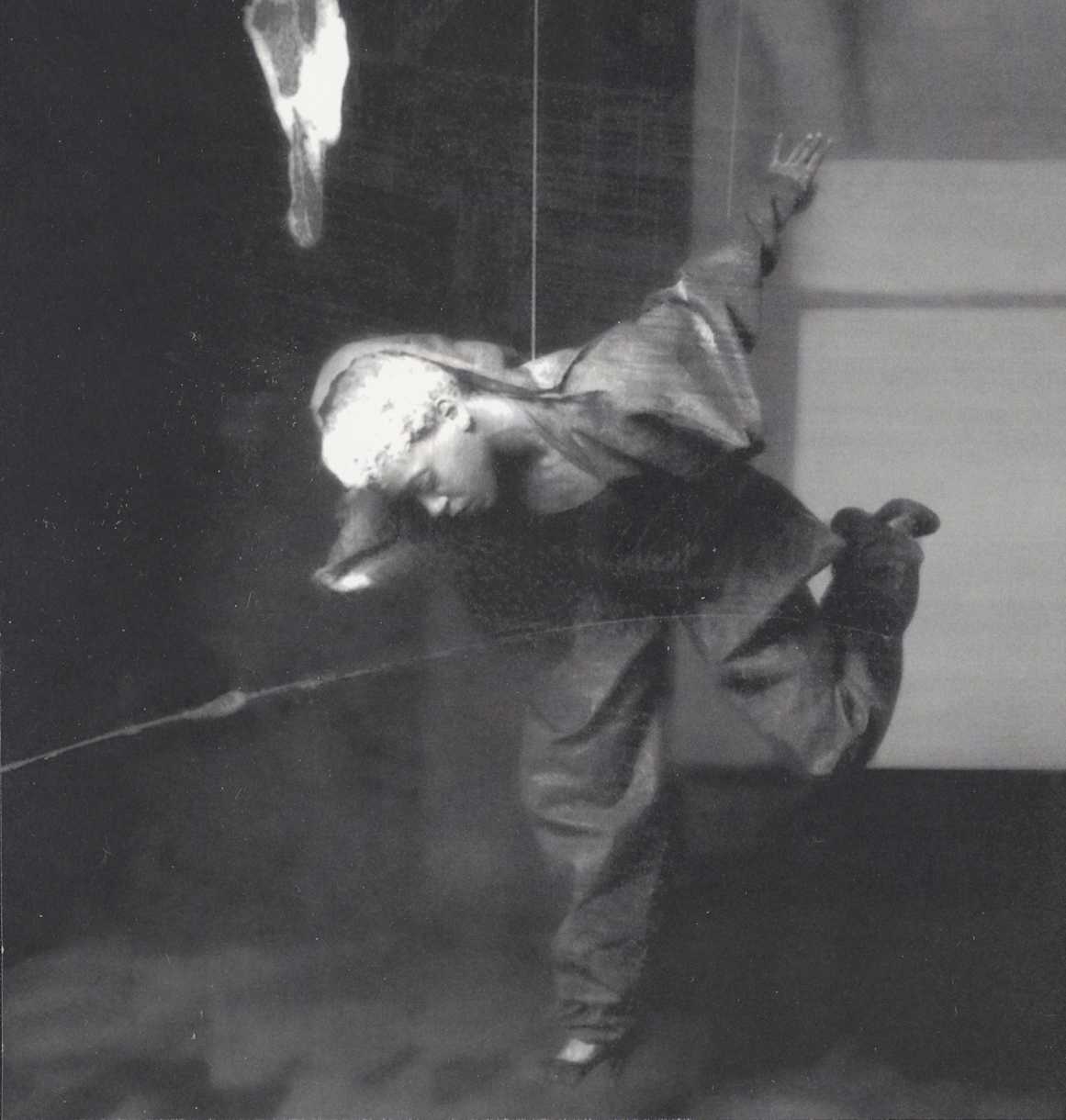

There were several other people in it. I didn't actually see that. I spoke my text, I hung on the swing. My hair was powdered white. And I had on a sort of costume, and I was laying across the swing sort of flying. I said the text, and it was sort of poetic. “I don't know what it could have been like when it gets some wind for the sailboat.” This is not Richie. This is Christopher Knowles. “When it gets some wind for the sailboat, and it could get those for it, it could get the railroad for these workers. Could be a balloon, could be Frankie, could be very fresh and clean. It could be. It could get some wind. Sweetest one. Well, these are the days my friend, and these are the days my friend. Would it get some wind with a sailboat? And it could get those for these, could get the railroad for these workers. It could be a balloon. It could be Frankie. It could be very fresh and clean. It could get something. The sweetest one. Oh, these are the days my friend. And these are the days my friend.” That's Christopher. [Applause].

That's a piece from Einstein on the Beach. I did Christopher's poetry and Einstein on the Beach. And he did, he wrote a lot of the material.

Audience: I have a question. So when you were, I mean you're talking about moving slowly, but on one occasion or during this one play, which was done so many times and you cut part of it out, you slowed to absolute stillness. Absolutely nothing happened. You had a raven and you said, and to me, I don't know what you were doing to me. You sat in absolute stillness. Who knows what you were thinking about. And after 15 minutes you stood up. What happened?

SS: That was really hard to do. I'll tell you why. Because you can't sit immobile for 25, 30 minutes without all these parts of your body falling asleep. What it feels like when your hand falls asleep within a minute. So it's really, really hard. So what I had to do was flex all the parts of my body internally while I'm sitting there, not visible to movement, but flex all these parts, especially the parts touching the chair, but the entire body. So you think about your breathing and you're relaxed. You're more than relaxed, and you have to do that from the inside so that stuff doesn't fall asleep. Then you reduce your heart rate so low that it's almost like falling asleep. You're almost asleep, but you're not. You're breathing nicely, calmly. It’s probably a good meditative practice in a way. Then of course you have to prep the moment that you stood up. So you're so relaxed that if you stood up suddenly you probably would fall down faint or something like that. So you're flexing in another way, in a broader way to prepare to stand up.

And then you stand up and then you try to breathe normally. Right? So I had a really terrible experience. There was a woman who was crazed and came onto the stage while I was sitting in the chair and completely relaxed. And she had her reasons. I don't know what it was. She grabbed me and my blood pressure, shot the roof, I was just trembling because it was so sudden it was kind of like I stood up too fast. But anyway, they got her off the stage and it shouldn't have happened. I think it is quite dangerous to have that happen. But sitting in the chair is really quite comfortable. So long as you are circulating your intention, you have to feel every part. You flex every part, and you breathe and breathe and breathe, and you calm yourself down almost to the point of sleeping almost. It sounds painful. I don't think it is. I think it's probably very good for you.

I think we could probably do that more often. Probably we do that when we're sitting down and don't have to perform it. That was the hardest thing I did in that act, was to be relaxed enough. If you come from something that's really exciting and you sit there, then you would need to pan. It was an interesting thing to do because it was startling to many people. They couldn't believe that I wasn't a statue. So when I stood up, they would gasp. It was a shock. Oh, it's a person. It's hard to get that still. It's extraordinary.

Audience: It was shocking when you stood up and you were an example to the group. But we didn't learn it.

SS: I didn't learn. Well, you weren't really asked to do it in a way, but you were asked to understand it. And I think everybody, all the times I did stuff first for the group, they understood something from it.

Audience: Every rehearsal began with Sheryl performing one of these pieces, cutting the onion, pouring the milk that you saw in the movie. Every rehearsal began with all of us watching Sheryl. So she was our muse too in that. And I didn't learn as much as I should’ve.

SS: Well, luckily you can move so you don't have to learn that it's important to move. Is that a question over there?

Julia Amsterdam (2024-2024 Archive Fellow, The Kitchen): Yes. I was helping prepare the items on the archive for the exhibition. And it was such a pleasure to hear you read that Christopher Knowles piece out loud. I was so curious what it would sound like. So thank you. My question is kind of a combination of questions—I'm curious how the memory of the choreography of all the shows that you've done live on in your body today, what feels present for you now? Especially with movements like cutting an onion and pouring milk, even though it's probably at least six times faster now when you're doing it. I'm curious. What those legacies look like for you now if they do?

SS: Well, I'm sure they're in there somewhere. They're in there somewhere, but you can't tell. I mean, I don't dance really, but when I do dance, then I can sense what used to be. I don't have to do anything with that intensity anymore. Even when I'm cooking in the kitchen, it is second nature. You don't have to prepare anything. There's nothing, no precision involved. I think that that was then, and this is now. What I'm trying to do now is just survive the demise of your body at this age. So I listen very carefully as much as I can. I try to practice breathing and some exercise. I do chair yoga. I don't know if you've heard of chair yoga. It's for elderly people to sit down and move a little bit like that. I think it is valuable.

It's really valuable because you still continue to make the connections. It's harder to move the older you get. So you do need some exercise in order to stay flexible. I'm sure it's good for circulation. I did a workshop with elderly people years ago, and these people were pretty much gone. They thought that's why because of how they treated them in the home. I did a workshop and we sat at the table and we flexed our fingers and we did repetitive gestures like that. I arrived at a place where even the most distant of individuals wanted to talk, and had stories. They started telling their stories. There's one woman who said, I had five children and they all had red hair. She would tell this story every time I came. I had five children and they all had red hair. So this was the pinnacle story left for her to tell other people about her life. And it meant she was still there. So everything is valuable.

Audience: Thank you for your conversation. It was really inspiring. I'm curious about how it was at that time, maybe at earlier times, to be provoked to have this very individual voice and to be certain about it. How was it for you to actually get to the process of trust (in collaboration)? I was actually with Bob last year, it's a very special process of trusting him or working with him. Still it was very interesting to see something of that processing within myself. So I'm really curious about your perspective.

SS: Yes, it’s like marriage. You really do have to trust and you really do doubt for a long time. At intermittent times, he'd ask us to do things and he'd say, “Oh, this is ridiculous.” Okay, I'm going to do it anyway. And then you do it and then you find out, well, what is that? I meant that I would say, “Okay,” and now I'm understanding what that is. He never explained anything; he didn't explain. He’s a director. He tells you what to do. He doesn't tell you how to do it. And that's so you can find it in yourself.

I am sure he still works like that today, of course. But in the old days, it was really painful. We sat in the 92nd Street Y against the wall and watched him go up to people and whisper their direction. We’d sit there for eight, 10 hours a day and we wouldn't know what's going on. We didn't know what that looked like. What does that look like on stage? Why are they doing that? Why do you tell that person to do that? And later on you understand that's exactly what that person should have done. I can't imagine them doing something better. And he just has a sixth sense about casting and choice. You had to believe for a while, but eventually you'd understand. My whole thing with Einstein was that I hated the music initially. I just hated it. I said, this is the music of the machines. This is not music. Where's the melody in this? These are arpeggios, people in studios. They practice this all the time.

“That's not music.” And then I understood after working for a long time, oh, the melody is not over four bars. It's not over eight bars, it's not over 16 bars, and it's not over 32 bars. The melody comes back, you have to wait for the melody. It's the music of the universe and the big bang, the universe explodes, explodes, explodes. And it's coming back. Just because you can't perceive the melody doesn't mean there isn't one. And oddly enough, I couldn't count it initially. And then eventually you reach the point where you don't even have to count. The changes come every four bars, 4, 8, 12, 60, 32. You don't even have to think about it. I know where it is. It's in you, you feel it. You feel the changes. I think that the biggest problem I had when we started Einstein was that why did he choose this music? What does that have to do with his theater? Then I think about Lucinda Childs on those three diagonals on the first day. And I say, yes, that's okay, that makes sense. My activity, which of course nobody appreciated or saw, was holding my arms up for all of the 20 minutes with a piece of paper and bombing my head like this. That's what I did while jumping through space. Okay. Nobody saw that. But that's what I got.

Audience: I have another question I was wondering about. That’s about when you did the piece. I mean talking about early days and more recent times and you in both phases of your life. So you did the piece in New Jersey about the story of Clementine Hunter and your acting style and movement style and whole repertoire is completely different than everybody else in that play. Your movement, you simply, as I remember, walked around. I don't remember what else you did. I watched you intently. I sat in a rocking chair. You did? Yes you did. I was in a rocking chair. I love that. So my attention… I was only in the audience. I had nothing to do with the show. Was I watching you because you're a friend? Or was I watching you because you, your movement pulled, or your movement pulled me in?

SS: That's it. The absolute stillness is always attractive. The eye goes right there. It's like these Chinese paintings that have the landscape and it's all gigantic like that and the little trees and everything, and the people are this big. You always find them. It's not that they're not important, they are the most important, but it's the scale because of the scale. You get it. So Bob’s stage is like that. But in Clementine Hunter, I had minimal things to do. I sat on the rocking chair, I walked through the space, but I walked through the space like me, not like them. They were performing like the Broadway singers. They were okay. They were performing great, wonderful music. So it was a contrast between my internalized eyes, 45 degrees inside. Everything was inside and Broadway out there. That was a big contrast between those two.

ER: All right. We're going to call it. Thank you so much.