Credits:

By Susana Plotts-Pineda, Winter/Spring 2022 Curatorial Intern

December 16, 2022

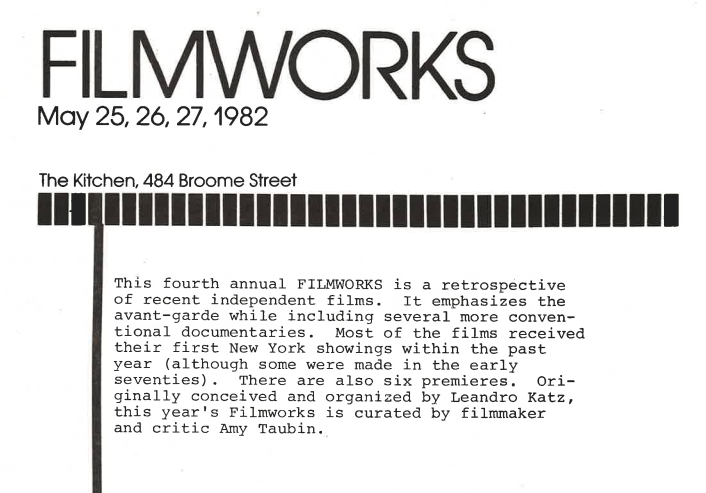

On May 25, 26, and 27, 1982, The Kitchen screened a series of experimental films from an array of emerging and established filmmakers. The fourth iteration of the Filmworks program series initially conceived in 1978 by Leonardo Katz, Filmworks ’82 was curated by author, filmmaker, critic, Kitchen artist and guest curator Amy Taubin. (1) As noted in the press release, the festival consisted of “16mm and super 8 work by over twenty filmmakers,” and was “a showcase for a variety of styles of independent work, with this [iteration’s] emphasis on that of the independent avant-garde but including documentary and other work.”

In addition to this press release, traces of the event glimmer to the surface via The Kitchen’s archive in a New York Times listing and a Villager review. As I looked further into the festival, I was struck by the contrast between the event’s extensive programming, which brought together an array of canonical experimental filmmakers, and its archival afterlife. I thought about what it means that the tangible, experiential quality of the events and the overall impact of the evenings can only be reconstituted through fragments of ephemera, despite the medium of film’s reproducibility. Kathleen Hulser’s review in the Villager offered some clarity on this matter, pointing to the status of independent film in a pre-digital age: “The art film is like a mushroom, it grows in dark places, nourished by obscurity.” Hulser attributes this obscurity to independent film’s existence outside of the art market, which, on one hand, freed it from commercial pressures and traditional notions of success, but, on the other, determined its relative absence from museums and museum collections. The review also points to the reality that independent film screenings often drew a sparse public, and it notes that The Kitchen was one of the few places in which the art film enjoyed a regular, enthusiastic audience.

Faced with the relative unknowability of the undocumented or unarchived aspects of the extensive three-day festival, I sought to trace the interconnected threads tessellating beneath text documents. I began to focus my attention on the screenings of filmmakers Laura Mulvey, Christine Choy, and Bette Gordon, whose works share intertwined formal and philosophical explorations of female pathos and its political, social, and symbolic manifestations. Their respective films, AMY! (1980), To Love, Honor, and Obey (1981), and Anybody’s Woman (1981) were shown at The Kitchen on May 26 and 27 and are emblematic of the festival’s wide scope and embrace of both experimental and documentary independent film.

It is possible to situate these films in a broader filmic genealogy born, in part, within the very walls of The Kitchen. The year before participating as a filmmaker in Filmworks ’82, Gordon organized a co-screening at The Kitchen in March 1981 of two films on British pilot Amy Johnson: Mulvey’s AMY! and Dorothy Azner’s Christopher Strong. Taubin reviewed this original screening in a Village Voice article titled “Aviatricks.” Notably, the work Gordon presented in the 1982 Filmworks festival calls back to the 1981 screening, as she references another of Azner’s films, Anybody’s Woman (1930), in her own Anybody’s Woman. Another precedent to Filmworks ’82 can be found in The Kitchen’s October 1981 programming, which included a workshop hosted by Third World Newsreel, the media company that produced Choy’s film. Dedicated to developing filmmakers and audiences of color, Third World Newsreel was founded with the drive to cover civil rights, anti-war, women’s rights, and decolonization movements throughout the world.

In this way, the three films by Mulvey, Choy, and Gordon presented in Filmworks ’82 might be read in conversation with each other through the lens of the feminist experimental praxis from which they emerge, as well as through the additional decolonial lens offered by Choy’s production context. AMY! was written and directed by frequent collaborators Mulvey and Peter Wollen, who are named in the Filmworks program as “among the most active figures of the British avant-garde.” The film, described by Taubin the Village Voice as “elliptical,” is a part-documentary, part-narrative, montage-driven biopic of Amy Johnson and her famous 1930 flight from England to Australia—a route that she was the first solo woman to complete. Composed of a series of letters, imagined moments of her life, aerial shots, cartographic shots, and voiceover interjections by Mulvey, the film problematizes the notion of female heroism, bringing to the fore Johnson’s exploitation by the press.

Choy’s To Love, Honor, and Obey is a documentary that sheds light on the personal and social impact of domestic violence through candid interviews with survivors, counselors, doctors, and police officers in several institutional settings. The direct cinema documentary is an unflinching portrayal of abuse and injustice, exploring how social, economic, and cultural factors contribute to cycles of violence and neglect in the home. The film reaches its striking conclusion when we discover that one of the many interviewees, a Black woman named Bernadette Powell, faces up to fifteen years in prison for killing her abusive husband in self-defense.

Gordon’s Anybody’s Woman, is an experimental short that blends fiction and documentary through a series of staged scenes and candid interviews with two members of the experimental theater company the Wooster Group—Nancy Reilly and Spaulding Gray—shots of Times Square and the Variety Theater on Third Ave, and an ongoing narration about Azner’s film of the same name. (2) Gordon’s version conveys equal parts fascination, disturbance, and humor at the fetishization and commodification of the female form at the hands of a Debordian “society of the spectacle” while often turning the voyeuristic gaze unto itself.

Read in tandem with one another, these three films illuminate the roles and archetypes to which women are condemned, relegated, or exalted in domestic, public, and historical spheres. In engaging with the films themselves, as well as with the ephemera from the archives, I was intrigued by how their distinct approaches to formal experimentation destabilize the vast iconography of female consumability, martyrdom, heroism, and suffering, offering new pathways for personal, social, and symbolic agency.

Deconstructing the Male Gaze

Mulvey is perhaps best known for her 1975 essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” which introduced the term “the male gaze” to film theory and is considered a foundational text in film studies. In the essay, Mulvey posits psychoanalysis as a weapon to combat the ways that the patriarchal unconscious has structured film form. Mulvey frames film as a “hermetically sealed world [that] unwinds magically” where the male subject realizes his idealized perception of self through voyeuristic separation. She articulates that mainstream narrative cinema makes use of visual pleasure to code the erotic into the language of patriarchy, turning the female figure into image, and the male figure into bearer of image and maker of meaning. As counterpoint to mainstream modes of film production, she proposes that independent cinema must reject visual pleasure and create “a new language of desire.”

One of the ways in which Mulvey and Wollen employ a feminist approach to independent film in AMY! is through the framework of theoretical filmmaking. In quotes included in Taubin’s article “Aviatricks,” Wollen articulates how in this mode of filmmaking “you indicate explicitly what the problem of the film is.” He identifies the problem of AMY! as that which is articulated in Mulvey’s voiceover monologue, wherein she polemicizes the notion of female heroism as “a wound in the symbolic flesh of family and law,” which must then be stabilized through “images, myths, and legends for the benefit of our identification and entertainment.” Wollen additionally expounds on the questions that inspired the film’s creation: “We were concerned with why Johnson became headline news and, more importantly, how;that [sic] she was immediately infantilized, as in that song we use, ‘Amy…Wonderful Amy.’” The song plays at the very end of the film to shots of Amy’s parked plane, in which her palpable absence seems to suggest the congealing of a mediatized fate at the cost of her own self-narrative, and ultimately her own life.

This moment is reminiscent of the opening of Choy’s film, in which Ella Fitzgerald’s “Love is Here to Stay” croons to a montage of vintage postcards, photographs, and paintings depicting idealized representations of love, marriage, and family. The sequence then cuts to sounds of sirens and a series of shocking photos of battered women. In this rupture, Choy proposes a direct and incisive attack on ideals of the nuclear family in contrast to the reality of women’s treatment in society. Interviewed in the film, Sandra Ramos of the domestic violence center Shelter our Sisters speculates that instances of domestic abuse derive from an ongoing history of persecution, which Choy then illustrates with a montage of witch burnings. This moment is a counterpoint to the opening sequence, offering a rapid-fire survey of the archetypes ingrained in the larger historical unconscious of patriarchy.

Overall, however, Choy’s film seems pointed toward uncovering how this patriarchal unconscious seeps into the daily realities of people’s lives. In one of the scenes of the film, policemen help a woman gather her belongings so she can safely leave her abusive home. When asked by an offscreen voice, presumably Choy’s, why he thinks that husbands hit their wives, one of the policemen replies, “I think it’s because they let them.” The camera flashes to what seems to be an incredulous expression on the woman’s face. Throughout many points of the film, interviewees speculate on what lies at the source of these kinds of attitudes: for instance, Ramos remarks on how women see themselves within a society where they are portrayed as marketable commodities. Choy goes on to illustrate a cause of why women perceive themselves this way in a sequence of shots of Times Square and its peep shows, adult movie theaters, posters, and X video stores, set to a crescendoing instrumental score. This passage echoes the opening of Gordon’s Anybody’s Woman and its overall scope as it engages with the erotic spectacle of commodification.

Troubling the Male Gaze

In her film, Gordon both engages and troubles permutations of the voyeuristic spectacle of pornography. In a staged scene near the beginning of Anybody’s Woman (below), Wooster Group member Reilly shuffles through a series of pornographic photographs in her apartment, while a voiceover recounts a scene from a Azner’s film of the same name, in which a couple of millionaires eavesdrop on the conversation of two showgirls. The two girls talk about how they don’t have any money and might soon turn to crime. The men can’t really hear what the women are saying, so they project a fantasy of two “hard-working girls” onto their conversation. Toward the end of the film, the voiceover continues, this time to night-shots of various theaters and stores (below). Much like Mulvey’s narratorial intervention in AMY!, Gordon deploys narrated text to articulate one of the central problems in her film: because the two girls are showgirls, they usually get paid to perform for “the male gaze,” but in this case, they are performing unintentionally and for no money.

This scene points to the larger economic forces that undergird erotic spectacle and push Gordon’s characters into the seedy underbelly of consumerism. The scene also echoes Choy’s highlighting of the economic framework of domestic violence and Mulvey’s analysis of the trope of the showgirl in “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” In that text, Mulvey situates this trope within an array of classic Hollywood films to posit that the showgirl freezes a film’s narrative into a moment of erotic contemplation. (3) Gordon turns this trope in on itself by transferring the moment of fascinated contemplation onto her female protagonist, Reilly, as she shuffles through photographs.

Gordon also engages the male gaze by alienating it from its usual context and tone. In a series of interviews, Wooster Group member Gray describes his experiences at various adult movie theaters. Gray’s retellings highlight what is for him an ultimately anti-erotic experience where “you couldn’t really get turned on” because of the strangeness and misplaced intimacy of the context. Gray recounts his interest in these theaters as an “intellectual exercise” and notes that in the adult films shown there, what compelled him were close-ups in which images were abstracted to the point of becoming “landscape.” Gray’s earnestness in describing the obscene often makes for a humorous effect. It seems Gordon is in some way neutralizing the male gaze by demystifying it and thus rendering it into something strange and ultimately banal.

In her own film, Mulvey attacks the male gaze by often opting instead for stark refusal. In what is arguably the most emblematic scene of the film, Amy appears before a black background and begins to apply make-up to a punk song, as her non-diegetic voice narrates the process of her mental collapse due to exploitation by the media. Amy then begins to draw the outline of her face on a transparent screen, breaking the fourth wall and intervening in the camera’s voyeuristic process, before emphatically crossing it out. In this scene, Mulvey recreates the “hermetically sealed space” of film in which the self, bound by the language of the patriarchal unconscious, is left to confront its own image in the chiasmatic emptiness of the screen. With the act of marking, Mulvey allows Amy to respond to this space with a resounding No!.

Towards a Female Gaze and the Possibility for Social Agency

While all three filmmakers employ different strategies to trouble the male gaze by activating alternate perspectives, their films also offer sites of agency. Gordon employs estrangement once again as a mode in which to channel a female gaze. In one scene from Anybody’s Woman, Reilly sits opposite actor Mark Heidrich in a coffee shop and tells an erotic story. Repetitively structured and populated with animals, her monologue holds the quality of a myth or a legend. Reilly is relentless in her narration, modulating her voice in a distinctly non-conversational tone, at once flat and emphatic. The delivery is somewhat reminiscent of the acting in pornographic films, highlighted by Gray in a later scene, but is also charged with an incantational quality. In this retelling, Gordon allows Reilly to hijack the process of voyeuristic production and become bearer of image. Through Reilly’s newfound agency, Gordon forges the space to evoke an alternate symbolic order within the film. Evading a rejection of the erotic, she chooses instead to release it from the spectacle of commodification into an alternate mythological unconscious, recreating what Mulvey might call “a new language of desire.”

Although structured around the notion of refusal, Mulvey’s film is also interjected with moments in which the gaze is reformulated and reclaimed—notably, in the intimate scenes of Amy in her home or flying past landscapes, during which the pilot’s letters are read. We are given the opportunity to see who the “real” Amy might have been and how she might have felt. In a final scene, we see a recording of her rejecting the notion that you must be famous to be a heroine.

In Choy’s film, this reclaiming of the gaze is primarily forged through its direct interview style. Choy gives women the platform to narrate their own stories of strife, articulate their contradictions, and, above all, reveal their resilience. In a final series of interviews her subjects relay their hopes for the future, offering perspectives on what “family,” “motherhood,” “martyrdom,” and “heroism” really mean. Choy proposes a materialist framing which provides an alternative to the primarily psychoanalytic approach Mulvey outlines in her essay. The description of Choy’s To Love, Honor, and Obey in the Filmworks program lists a series of questions that her interviews pose, such as “What are the social pressures that provoke men to violence?” and “What are the attitudes of the criminal justice system towards domestic violence?” Through Bernadette Powell’s real-life tragedy, Choy reminds us of the intersecting systemic forces of gender, race, and class.

In one of the film’s interviews, Dr. Helen Rodriguez expounds on the difficulties of raising a family in the context of rampant unemployment and precarious housing. In fact, throughout the film we are witness to the social realities of poverty, racial injustice, and the immigrant experience in America. Choy points to the stark isolation and lack of social support structures that create cycles of trauma and abuse. What is offered at the end of the film is a tender sense of hope for its subjects, but also, tentatively, a reaching towards a common future in which we may work to transform the material structures that surround us.

Filmworks ’82 as a site of potential

AMY!, Anybody’s Woman, and To Love, Honor, and Obey engage different approaches to destabilizing the patriarchal gaze and the archetypes of passivity, consumability, and martyrdom that the gaze casts in distinct but interrelated domestic, social, and historical spheres. Through experimental, documentary, and theoretical practices, these films offer moments in which an alternate gaze is posited and exalted. At times, these sites of potential emerge through a restructuring of the symbolic order within the film itself, while other times, they point outside of the realm of representation into economic, social, and historical contexts.

Mulvey, Gordon, and Choy have gone on to receive due recognition for their seminal contributions to the feminist film canon throughout their long careers. And while broader, probing conversations on gender and feminism have permeated experimental and documentary filmmaking in the years since 1982, the nights of Filmworks ’82 represent a seminal moment when these three filmmakers offered striking proposals of a feminist gaze set against the normative bounds of their context––proposals against which contemporary filmmakers continue to project the scaffolding of an ever more confrontational, queer, decolonial, and radical gaze.

Images and videos: 1) Program for Filmworks ’82 at The Kitchen, May 25–27, 1982. Detail. To see the full program, click here. 2) Still from Laura Mulvey and Peter Wollen, AMY!, 1980. Courtesy of Arsenal - Institut für Film und Videokunst e.V., Berlin. 3) Left and right: Excerpts from Bette Gordon, Anybody’s Woman, 1981. Courtesy of the artist. 4) Still from Laura Mulvey and Peter Wollen, AMY!, 1980. Courtesy of Arsenal - Institut für Film und Videokunst e.V., Berlin. 5) Excerpt from Bette Gordon, Anybody’s Woman, 1981. Courtesy of the artist. 6) Still from Laura Mulvey and Peter Wollen, AMY!, 1980. Courtesy of Arsenal - Institut für Film und Videokunst e.V., Berlin. 7) Left and right: Stills from Christine Choy, To Love, Honor, and Obey, 1981. Courtesy of Third World Newsreel.

Footnotes: (1) Taubin went on to serve as Film/Video Curator at The Kitchen from September 1982 through 1988. (2) In many ways Anybody’s Woman can be understood as a sketch for Gordon’s subsequent 1983 feature Variety. For instance, the Variety Theater on Third Ave that appears in Anybody’s Woman was a source of fascination for Gordon and later became the set for Variety. (3) She describes how interludes within the narrative arc of mainstream films at large create a “no man’s land outside its own time and space” in which the gaze of the spectator merges with that of the character.