Credits:

Gyula Muskovics

August 14, 2024

I am in Tribeca, on Duane Street, visiting Pat Oleszko for the first time in her apartment loft. It is an unusually warm February afternoon—after our 3-hour long interview, I spent the night walking by the west side piers, and I don’t remember being cold at all. I buzz, she lets me in, and I find myself in a narrow staircase decorated with funny little things in Pat Oleszko style. When I reach the fourth floor—where she has lived and had her studio since 1970—Pat cheerfully opens the door. We introduce ourselves and she offers me some delicious red wine and makes an espresso—with a slice of lime in the cup—on a giant, steampunk espresso machine from the previous century. Then we sit down at the table—facing one another—and start talking. Hats of all colors and patterns hang over her head. Pat is in the arduous process of organizing her “two dimensional” archives, which will soon go to, as she says, “the unfortunately named Fales Collection,” at NYU Libraries.

Pat Oleszko's solo exhibition— Pat's Imperfect Present Tense ran through July, 2024 at David Peter Francis

Gyula Muskovics: What does it feel like revisiting your whole body of work?

Pat Oleszko: When you’re going through your archive, you’re going through your life in slow motion and there are all the letters and the gigs and all the stuff in between. I’ve barely been able to make anything lately because this process takes up not only mental space, but also a lot of physical space. I will be happy to get it out of the house to some place that would be accessible to somebody because I have been doing stuff in this loft since 1970 and it’s a lot of history sequestered here.

GyM: What about your costumes?

PO: No place really wants costumes; they are extraordinarily difficult to maintain because they are of fibers, paper, plastics and much else, are constructed to be worn (and worn they are I might add). I used to have three-and-a-half storage spaces, of which one was at my old boyfriend’s loft. But I’ve done all these ritual cleansings lately where I construct a site-specific performative event which culminates in a mighty conflagration of old works. So, I’ve gotten rid of a lot of stuff that way. And fortunately, some things have been wrenched from the fire by wiser heads.

GyM: Tell me more.

PO: Early on when I was living on the Bowery, I threw stuff out and in the ensuing weeks I would see the homeless men wearing pieces of my costumes. It was humiliating and wonderful at the same time—although I didn’t think to capture that piece of Dada with my doodoo on film. However, I periodically realize that I should throw this stuff away, cull the collection, because I’d already used them many times, or their time is up, or they’re taking up too much space, or I don’t love them enough. There’s usually a procession and there might be some storyline, and an extravagant performance that eventually ends up at the sacrificial site where with histrionics and flair, I light it afire. Then there’s this incredible transmigration of the souls that goes on for hours, a meaningful exit for the eons of work, thought and creative juicing. It is electrifying, joyful, draining and cathartic and I am crying and laughing and totally exhausted at the end, so many parts of me, “Pa’ts” of me, glowing with the embers, I am unable to speak.

But there are many other things created. For example, I used to make inflatables. I’ve made sixty or seventy, from costume size to a 60-foot rocket ship sewn out of ripstop nylon that you can’t just burn. It melts and smells and is an ecological nightmare. Also, the material breaks down after a certain amount of time and it starts to smell like vomit--easily the least attractive of scents. Washing dozens of yards is impossible or prohibitively expensive. So, I’ve got a problem there…

GyM: And you are putting them in the trash instead of a museum…But let’s go back to the beginning. How did this whole idea come about to make costumes? I mean, is costume the word you would use?

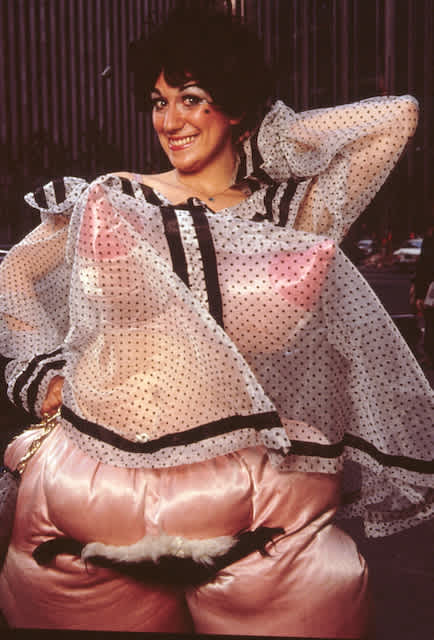

PO: They were sculptures, or not. I called it pedestrian art because it walked, it talked, it farted, it fucked. I was a sculpture major at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor and wanted to make big sculptures but I didn’t learn how to weld properly so everything kept falling over. Too humiliated to withstand the derision of my mostly male cohorts, I started working at home. I had a sewing machine, was making these things and then looking for an armature, and I started just hanging my sculptures on myself. I was six feet tall and could carry anything I could make and—not fall over. At that moment, my art walked out the door and I began using all the world as a stooge. Everything became a platform. I started in the streets, then every year I went to the Ann Arbor Film Festival creating works on stage there, non-cinematic performances before the shows. I also worked in burlesque in Toledo [Ohio], as Pat the Hippie Strippy, another place I used to experiment with performance ideas, and moved to New York because it was The Cultural Center, the Land of Oz and there was plenty to see and learn. There was no name for performance art at the time but that didn’t stop me. I worked parades, restaurants, beauty contests, films, magazines and wherever I saw a need to poke fun at seriousness ever resplendent.

GyM: Did you make these pieces to create a new identity?

PO: Well, when I was growing up, I had a lot of energy. But I was way too big and way too expressive, even excessive, for most men and, as a woman, especially when you’re young, if you’re not getting play from the opposite sex, it really hurts. And so all of my earlier pieces were addressing the problem of femininity and a good part of them were somewhat brutally sexual. But it was funny. It was bold, and I walked the streets of New York as a sartorially enhanced satire attracting crowds, or not, always a sociological experiment.

The fact that I was playing with sexuality that seemed to be so evasive, that I was making a joke out of it, put me in control of the situation. My world is firmly situated in the ridiculous and the wide range of humor, even when I’m working with quite serious subjects. It also amuses me, so it also functions in liberating me from whatever fears or trepidation. I force myself to confront my selves.

GyM: So, in a way, the costume protects you and makes you a person of strength.

PO: I see myself historically like the fool or the shaman where you have the position of being extreme and also artfully ridiculous. You can play with all the politics, or the social inequities and you have power because it is so exaggerated and without traditional restraint. It’s challenging for a lot of people. I’ve been arrested a number of times because I was wearing a costume in a place that they didn’t want me.

GyM: Arrested?

PO: Well, I do a lot of political work, so I play it carefully if I’m wearing an elaborate costume, not to get thrown in jail for protesting. But when I presented myself as the NincomPope at the Vatican, distributing Holy Water with a gold-painted Super Soaker, I was arrested, and thrown in the Vatican jail.

GyM: For how long?

PO: Eight hours, so it was kind of a badge of honor.

GyM: The thing with humor is that people can’t really control their reaction to it. This is why it’s dangerous.

PO: I think that humor is incredibly powerful, and I take it very seriously. And when you’re talking about it in terms of drag or fashion, there’s a level of understood humor.

GyM: Are you talking about camp?

PO: Exactly. Have you heard of Stephen Varble? He would make his costumes totally out of trash and walk the streets. He’d appear on the street dressed up with a chandelier on his head and stuff like that. He was very beguiling and irreverent in the best possible way.

GyM: As people recall, Klaus Nomi could also be spotted in the streets of New York as this androgynous, outlandish creature from outer space. Did you know him?

PO: We met a couple of times. But we all knew each other because everybody was in the clubs.

GyM: Which clubs did you go to?

PO: The Mudd Club, the Palladium, the Studio 54, Wetlands. You know, New York was falling apart in the ‘70s and the ‘80s and it was dangerous, filthy, and ugly, but it was also cheap so you could come here, find a place, make stuff, go to parties every night and get in for free—if you looked fabulous. Everything was possible because it was a mess.

GyM: Is there a particular outfit that comes to your mind?

PO: Once I made a costume that was completely covered in plastic champagne glasses. I wore it to a lot of different opening type events, with my escort as Escork wearing a jacket of corks. But there were a lot of pieces that I wore only once; I’d kill myself making the piece and then didn’t keep it—a one night stand.

GyM: What did you do during the day? I mean, where did you work when you moved to New York?

PO: Everything happened pretty fast. Of course, I waitressed, but only for two years, I think. And in that time, I got a couple of shows. I had a big one at the Museum of Contemporary Crafts in 1971—which is now the Museum of Art and Design— I had a whole room to myself. The title of the piece was New Yuck Womun and I made these eight really overblown caricatures of New York women, with hugely exaggerated breasts, pussy and ass. You know, there was a Playboy bunny, a little old lady, a secretary with huge tits. And then I started getting grants and I quit my waitressing job. I thought, oh, I’m on my way, which was a little too early, so I had to borrow money.

GyM: And then you found this apartment loft.

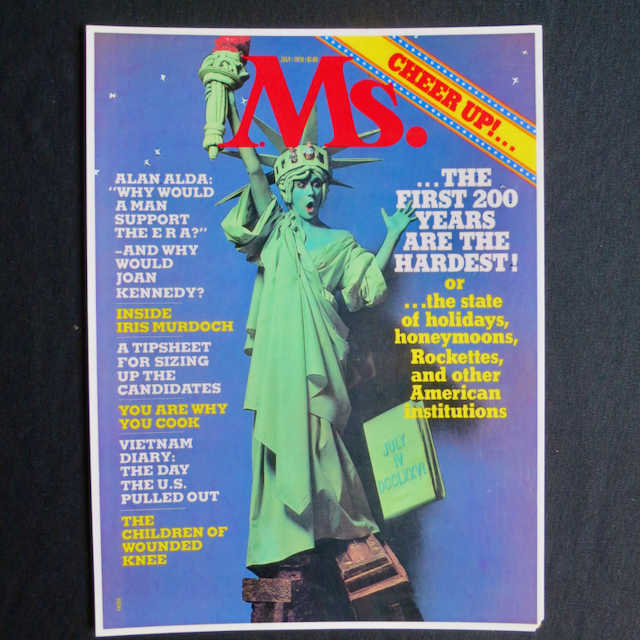

PO: Yes, two years on the Bowery and then I found this loft. I also had the idea that I could use my sculptures for illustrations. That was back when magazines were more visually and conceptually experimental. I sold myself to a lot of them, like Esquire, Playboy, Ms, New York Magazine, Sesame Street Magazine. I impersonated Norman Mailer once and I was a Statue of Liberty on the Cover of Ms. Magazine.

Pat opens her portfolio—an old, cardboard dossier with press clippings and photographs from the ‘70s and the ‘80s—and points to a man wearing a Santa Claus costume.

PO: So, this is supposed to be Rudolf Nureyev.

GyM: Did you make a Santa Claus costume for Nureyev?

PO: No, I sewed the costume and Esquire put it on a dancer who looked about the same size as Nureyev. The montage pastiche was by Jean-Paul Goude, a very well-known designer who used to be married to Grace Jones and made all her great looks. It was easy. I knew one person, and that person would get me into another place and so on. But I didn’t have the same luck with the galleries. I walked into a gallery, and they would immediately throw me out. But thanks to this museum and these magazines, I realized that I could do stuff that was quite public which was important for me. Then I did an evening at the Museum of Modern Art [Pat is referring to the evening when she dressed up as a Checker Cab for The Taxi Project (1976) show at MoMA and gave her cards to people like Elizabeth Taylor—who never called her] and I also started entering festivals and parades wearing elaborate costumes. But those were things that I just did on my own.

GyM: Is this what you did at the Ann Arbor Film Festival before moving to New York?

PO: Yes, it’s the oldest festival for underground films in the country. And when I was there going to school, I would make a different elaborate costume for every night of films. That would be six nights. And then I started doing performances every night before all the films where I really performed on the stage for the first times.

GyM: Were these commissioned performances?

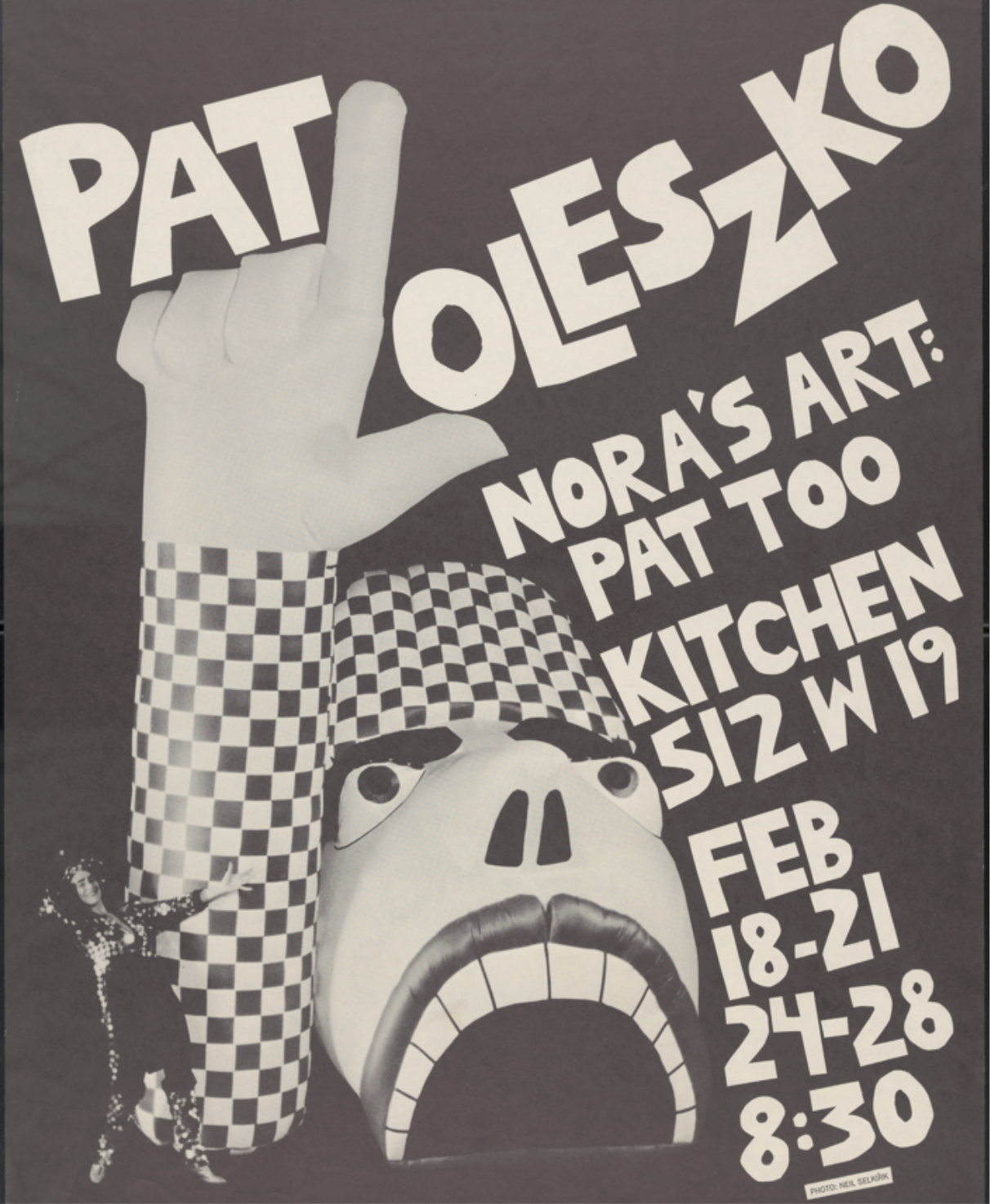

PO: Not at all. I did it while I was there for five years and when I came to New York, I kept going back. So, every year I would do six new pieces that got to be more and more elaborate. And then I started putting these pieces together to make a longer piece. I started performing at The Kitchen and then at PS 122, Franklin Furnace, Dixon Place and many other places.

Pat shows me a picture of The Coat of Arms, a beautiful costume—which was created for the fiftieth anniversary of the Surrealist Manifesto in 1972 and has become one of her signature pieces—and then another one where she is dressed in colorful plastic cups, standing behind a goat.

PO: This piece I created for a performance at PS 122. Every year they would have a fundraising Benefit, so I volunteered to sell beer because I wanted to get in for free. I made the costume out of plastic beer cups so I would look appropriate. When I got there, they said, “Oh no, you look too fabulous to sell beer; you just stand there and look great.” Anyhow, after that, every year I was commissioned to make something that would interpret the idea of the Benefit and became the Lottery Queen as well. I did it for twelve years, each year having to outdo myself, so I was just as happy when they retired the idea.

GyM: And you would start touring in Europe by the early ‘80s, right?

PO: All over the country, a lot to Europe, Canada, Japan… In 1980 I was invited to Mondial du Théâtre in Nancy, France. It was the year when Pina Bausch did Café Müller there and the filmmaker Werner Schroeter made a documentary about the festival and featured her and a few of us in the film called Repetition General (Dress Rehearsal). The festival was a place where you would go and see theater from 10 in the morning until late at night and every evening there’s dancing until dawn, so it was exciting on every level. And every single day was a whole new look for me that was made for the moment. So, I think that I gained a significant reputation from that as well.

GyM: Is Oleszko a Polish name?

PO: Yes, my father was Polish, my mother’s German.

GyM: Did you have a chance to travel to the Eastern Bloc before the fall of the Iron Curtain?

PO: Yes, I was in Poland during Solidarity, I was invited to the Wroclaw International Festival of Theater in 1981.

GyM: This sounds interesting!

PO: It was an astonishing festival! They brought everybody in from all over the world, from Israel, Palestine, Germany, Japan… and we were doing stuff in the streets—a big group thing that I kind of organized. There was one slide projector, one hammer and two nails, they had nothing, but the spirit of the people was incredible.

GyM: How did you get invited?

PO: I was performing a lot in New York, and I guess one of the organizers came to see a show and invited me. What I remember is that they sent me a one-way ticket, which was very peculiar. Later they told me it’s cheaper to buy the ticket from Poland to New York than to buy a round trip. Anyhow, it was a huge experience but it’s a very long story and I don’t know if I ever recovered from that.

The story is indeed long and convoluted. To begin with, Pat remembers it as one of the best conversations of her life, when she and the other artists at the festival were sitting around a huge table brainstorming about a project they would realize together—with a lot of vodka at hand but without speaking a common language. Eventually, they decided to do something for the people in the city. They ended up throwing white house paint—and later some colors, too, that one of the local artists had at home—onto the windows of the stores on the main walking street. And the townspeople would join them so the whole thing would become a collective performance—kind of like a collective Jackson Pollock piece. But the exciting part comes at the end of the day. There is a closing party, again with a lot of vodka, the locals sing a song to Pat, a song from her Dad’s village—Pat is very drunk so moved by this song she cannot stop crying. Her contact lens turns out of her eye, so she goes to the bathroom to put it back in, but she passes out. When she wakes up, the party is over, everyone is gone, and someone has stolen her passport. There she stands, without passport and ticket in Wroclaw—her flight from Warsaw to New York is leaving that day. All of this would have been okay, but she had a $20,000 job for a big corporation that she had been preparing for two months before she went to Poland, and they were coming to look at it the day that she was supposed to come back. And miraculously she made it! When the taxi parked in front of the house, the corporate people were already there with Pat’s assistant in the studio, and Pat, leaving her suitcases downstairs, ran up as if she had just went to the store for a bottle of milk, “Hi, well, where were we?”—and, at the end of the story she says,“You know, everything was perfect.”

Well, not entirely. We are back in New York, it’s 1981, and the first articles appear in The New York Times about a rare, rapidly fatal type of cancer that mostly affected gay men.

GyM: If we speak about the 1980s, I think, we cannot avoid talking about the AIDS crisis—given that the epidemic hugely impacted the scene you were also a part of. Could you talk about your experiences?

PO: Well, as I said, the art world was like a village. Everybody knew everybody and during this time you would always hear about people dying. Like our community was being destroyed from within. It wasn’t just friends that you were losing but the very pillars of our church. Ethyl [Eichelberger] committed suicide; he had AIDS. Charles Ludlum, brilliant and influential theater artist died at the height of his powers. It was a terrible time to keep going in the midst of it. Act Up protests were going on in the streets and there was a kind of gloom, this kind of oppressive gloom that everybody was fighting against all the time. I mean, you might lose your best friend or four friends that weren’t so close, but you were attending funerals all the time. Everybody addressed it in their own way. There was, for example, a female musician, a singer with an incredible range, called Diamanda Galás, who had lost her brother from AIDS, and said that she was going to do her Mass—where she’s shrieking in this incredible makeup and stage presence, until they solved the AIDS crisis. And she did it for a very long time.

GyM: How did you respond to it in your work?

PO: I did a couple of pieces about the plague. I made a coat, hat and bracelets, completely covered in real animal bones. It was originally made for AIDS and then it became something that I wore to a memorial for John Cage and a few other notable people. There was an event in ’85 or ’86 in Central Park where a lot of people were doing stuff about AIDS. It was more organic than organized but we just came to the Sheep Meadow one Saturday and everyone did what had to be done.

Pat shows a dark phalanx of five ghost-like characters under umbrellas.

PO: This was a piece called The O-Men, I’m the character in the middle and we would literally swoop like five birds. It could be said to have a haunting presence, all black with black spooks under black umbrellas. That was my piece in the Central Park Meadow, which I originally created for Artpark in 1976, and also wore for the Halloween parade another year. Some pieces have many varied lives.

GyM: Could irony or humor serve as a tool for coping with this huge amount of loss that you talked about?

PO: Well, Act Up and their performances were so confrontational and strident that, in my opinion, they were always done with a sense of irony to help bring people to awareness. But I personally didn’t see manifestations of lightness or humor much. It was too close. You must get distance before you can work that way. I did a big piece about 9/11 and, you know, it happened only four blocks from me…

Pat looks out the window.

GyM: What happened to this area?

PO: We were covered with the dust and death and detritus of the World Trade Center.

GyM: Were you at home?

PO: I was voting, two blocks closer there. I didn’t hear anything, but when I went outside everybody was pointing toward the big hole in the Trade Center that was on fire. I thought it was an error… and then the other plane came, and a tsunami of smoke enveloped the area… so everybody started screaming and running down the street. You could see people jumping out the window, holding hands or holding their shirts over themselves. And it was… I thought the world ended.

GyM: You were so close! How could you avoid being covered by the dust?

PO: We were running, and it more or less stopped at my street.

GyM: Did you have to move out?

PO: I did not. I stayed, and worked in the rescue and the cleanup operation, with the Red Cross and others for a couple of weeks. I ran a re-supply place on the street right before the rescue workers went in to work on the Pile. One day I had a dentist appointment, so I went uptown, and everybody was sitting outside, having coffee and… you know, we were down here and thought the world ended… I didn’t think I was going to make art anymore.

GyM: But then you changed your mind and did a piece.

PO: Yes, I wrote a letter, addressed to my friends who were calling me after 9/11, and it became the basis for a performance—Rubble with Pause (2002)—that was about my relationship with the (World) Trade Center; I had all kinds of stories there.

GyM: Tell me one.

PO: One time I picked up some guy from Yugoslavia, and when we left the bar, it was 5 in the morning, I said “I’ll show you the Trade Center,” so we walked there and got into the elevator and rode to the top. You know, there was no security, and it was completely open. There was a fancy restaurant where we helped ourselves to some excellent brandy, and as the sun was streaming through the windows, those windows on the world, we made love in all four corners of the place.

GyM: When did this happen?

PO: In 1982, I guess. Can you imagine this today?

GyM: It sounds like a very special memory.

PO: Yes, and the letter I was reading contained similar stories… It took me a long time to find a way to insert something that was funny about it, but I eventually found it. The performance wasn’t as elaborate as some of my other pieces, but I always had a question-and-answer at the end, so people could ask or voice their opinions and things like that—they were laughing and crying at the same time and I’d never ever done anything like that before. It was an amazing experience.

GyM: I’m happy that we arrived at this point. How can we respond, through humor, to a catastrophe?

PO: It’s the absurdity that fires me up—which turns out to be humor. You know, so many of our social mores and constructs are so ludicrous. We’re living in a country where half of the citizens think that Donald Trump is their savior—and they are so blinded. In the ‘60s, and the ‘70s and the ‘80s Republicans and Democrats would, of course, have problems but they wouldn’t completely reject each other. Today the country is so very polarized; I can’t really imagine having a conversation with someone who’s destroying the country as led by narcissist and con man with a Party taking away women’s reproductive rights plus making it horrible for children to come into their own—especially if they are non-binary or trans—amongst other things too dreadful to go into without despairing violently.

Sometimes I’m thinking about all this and ask myself, “Where the fuck am I? How could anyone find humor in this?”

GyM: Any ideas?

PO: I just did a big piece about the book bans. That started a couple years ago in Florida, and they have banned 1600 books already. That is astounding is it not? Anyhow, I was invited to a photographic festival about the Beats, the poets and the movement— which was being held in a library. I’d gathered a lot of the books that were banned so it was most peculiar, I thought, to be taking a bunch of books down to Florida, to a library. When I got down there, distributed the books, I made everybody read them aloud together. Eventually they were all reading the books, twenty-five of them simultaneously, making a huge, wondrous cacophony of words, banned words and thoughts. A lot of the books were truly excellent and, well, it got to be a great communal performance. They were so into it. It was a big room, with a stage, I had a musician, and was in a very elaborate costume. The audience just kept reading and declaiming as it kept getting louder and louder, and, at the end of it, they said, “We have to take this to the steps of the Capitol.”

We both laugh.

Some time passes.

GyM: It’s your first solo exhibition in New York City since the 1990s. What does it feel like?

PO: It is huge, wondrous news. There will also be a performance on the Staten Island Ferry entitled The Future is For/Boating. Being in a gallery is not part of my usual practice, although I have had museum shows, this constitutes a completely different direction for me. The show is a survey, with costumes and props, hats, videos and inflatables from all ages and rages of my past. The possibilities of being shown this way are endless. The gallerist David Pagliarulo is young, knowledgeable and enthusiastic about finally giving me my due as a performance pioneer and providing me a forum for other directions including, god forbid, selling the work! Who would’ve thought, at this point in time, I would be getting my close-up? I am delighted to see the costumes et alia come out of somnolence and overuse and put on the stage again, albeit one of the most traditional of all, as stabiles in a gallery, and to see what will result. Maybe, just maybe, I will sell something, and they will all not be consigned to the flames but to the future. And if not, well okay, it took many hours to bring the work up to speed, polished and repaired after such a long history of performing anywhere and everywhere, but now they are ready for another and quite different journey into the world at large without me inside. I wonder if I can handle it?

BIOS

Gyula Muskovics is a curator, writer, artist, and cofounder of the Hollow immersive performance art group. From Fall 2023 to Spring 2024 he was a Fulbright visiting researcher at The Museum of Modern Art and from Fall 2024, he will be a Rosztoczy Foundation fellow at the NYU Special Collections Center in New York. Gyula’s works and publications are motivated by a pull toward the edge and revolve around subversion, queer desire, intimacy, and the political capabilities of the body. He is currently a PhD candidate at the Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design in Budapest. He has performed, created and curated events in off-sites, theaters, galleries, and festivals across Europe. He has given talks at nGbK and Slavs and Tatar’s Pickle Bar in Berlin, the School of Visual Arts in New York and the University of Chicago. His essays and articles have appeared in The European Journal of Women Studies, DIK Fagazine, CTM Magazine, and post – MoMA.

Pat Oleszko: A multi-disciplined Artist of Some Repute, Oleszko has worked from the popular art forms of the street, party, parade, stage, film and burlesque house, to the Museum of Modern Art and Lincoln Center, from Sesame Street Magazine to Ms, Playboy and Artforum. Literally a much decorated artist, she has been rewarded for her perverse efforts including 4 NEA grants, 4 NYFA's, the Rome Prize, a Guggenheim, the DAAD (Berlin) and a Bessie for Sustained Achievement.