Credits:

By Elizabeth Wiet, 2019–2020 Curatorial Fellow

April 13, 2020

Following the conversation that The Kitchen hosted between Dara Birnbaum and Sondra Perry on February 15, I was moved to write an essay exploring The Kitchen’s history of supporting video made by female artists and assessing the formal and thematic concerns linking their work. Bringing in Gretchen Bender as an intermediary interlocutor, I closely analyze Birnbaum’s single-channel video Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman (1978–1979), Bender’s multi-channel video Total Recall (1987), and Perry’s exhibition Resident Evil (2016), with the aim of drawing connections between the ways the three artists have used video to “talk back” to the media by deconstructing the sexist, racist, and capitalist images that often circulate on TV and the internet.

Birnbaum presented several video works—now canonized and well-known—at The Kitchen in the late 1970s and early ’80s: (A) Drift of Politics: Two Women Are Active in a Space (1978), Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman (1979), and Pop-Pop-Video (1980), a month-long exhibition in which Birnbaum edited the videos Kojak/Wang and General Hospital/Olympic Women Speed Skating in real time, with live musical accompaniment. Bender’s Dumping Core and Total Recall respectively premiered at The Kitchen in 1984 and 1987. In 2013, The Kitchen presented Tracking the Thrill, a retrospective of Bender’s work co-organized with The Poor Farm. Birnbaum participated in a panel discussion as part of the exhibition’s programming. Perry’s Resident Evil exhibition was on view at The Kitchen in 2016.

IN AN AGE when anyone with internet access can download a digital file of a TV show in order to create a mash-up for YouTube or a GIF for Twitter, it is easy to forget that, for most of the medium’s history, television was a one-way stream. By 1977, the average American family was watching television some seven hours and twenty minutes per day. And yet, despite what artist Dara Birnbaum once called television’s “seemingly seamless flow,” it remained elusive, ungraspable—it was broadcast into private homes, but Americans could not possess it, could not physically hold it the way they could a book or painting. This is what made television, in Birnbaum’s view, a particularly pernicious medium. TV could act upon us, dizzying us with images of violence, sex, and consumer goods, but we could not act upon it.

Though trained as an architect, Birnbaum turned to making video art in order to “talk back” to TV. In the videos she created throughout the late 1970s and early ’80s, Birnbaum spliced, edited, and radically reconfigured clips from popular television shows—Wonder Woman, Laverne & Shirley, Hollywood Squares—in order to expose the ideologies embedded deep within them. With a razor-sharp understanding of televisual semiotics, Birnbaum used the conventions of each TV genre against itself: to critique the conservative gender politics of Laverne & Shirley, she employed the classic sitcom two-shot; to equate the subtle violence of corporate advertising with the spectacular violence of police shoot-outs in shows such as Kojak, she exploited the crime drama reverse-shot. Few critics are capable of describing Birnbaum’s video practice without mentioning the “rapid-fire” editing techniques that make works like Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman (1978–1979) and Kojak/Wang (1980) so disorienting. But in repeating select scenes from these shows over and over again, Birnbaum sought to create moments of suspension and arrest—to force the viewer to pause and to consider precisely what political logics were at play in the images that they were seeing.

Clocking in at just under six minutes, Technology/Transformation became Birnbaum’s best-known piece. To make the video, Birnbaum adopted a “repeat-edit strategy,” cutting between scenes of screen-filling explosions and scenes of Diana Prince, the show’s eponymous heroine, spinning out of her civilian clothes and into her costume. The character of Wonder Woman was developed by DC Comics in 1941 to combat what Harvard psychologist William Moulton Marston called the “blood curdling masculinity” of superhero comic books, and by the 1970s she had become a somewhat complicated feminist icon, even appearing on the cover of Ms. Magazine in 1972 under the headline “Wonder Woman for President.” But Birnbaum found the idealized depiction of feminine power that the character represented to be empty—even stifling. “You either heroize her, or you underrate her as a secretary,” she said in a recent interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist. “The burst of light says that I’m a secretary—I’m a Wonder Woman. Where I am is in between.” Spinning like a toy top, Wonder Woman’s agency is not entirely her own. Rather, it belongs, in Birnbaum’s view, to the TV industry—to an industry where men used the figure of the superheroine as a ruse to market what she called, in a 2002 interview with Nicolás Guagnini, a “commodified, corporate image of women.”

Birnbaum’s politically minded, appropriation-driven works required unprecedented methods for obtaining raw material. Consumer cameras such as the Sony Portapak, engineered to record new video footage, had become a mainstay by the mid-1970s within artists’ studios and private homes. But another piece of equipment was not yet accessible to most Americans: the VCR. Without a VCR to record shows such as Wonder Woman at home, Birnbaum had to act surreptitiously, often obtaining bootlegged footage from friends who worked at television networks or relying on the good graces of unusually magnanimous local station producers. Birnbaum’s practice of furtively purloining physical television footage earned her the moniker of TV “pirate.” Like a pirate commandeering a cargo ship, she seized commodities (in this case, televisual images of women) from the entities that owned them. These images, she felt, “belonged” to her as much as they did their original corporate makers. But Birnbaum did not hoard her pirated loot for herself. Rather, she disseminated her edited videos within the circuits in which they were originally broadcast—even airing Technology/Transformation on cable TV opposite the Friday night CBS run of Wonder Woman in 1979.

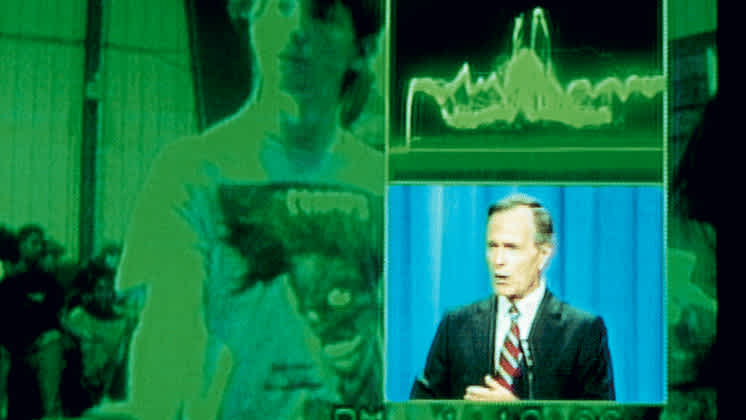

THOUGH IT HAD BEEN “NEARLY IMPOSSIBLE” for Birnbaum “to have direct access to television’s imagery” in 1978, she wrote in the 1985 essay “Talking Back to the Media” that by the mid-1980s, it was “nearly impossible to not have that access.” The arrival of the VCR into the consumer market made it much easier for video artists to pirate televisual footage, and as a result, video works that incorporated TV images became increasingly complex. Videos like Technology/Transformation served as important reference points for artists such as Gretchen Bender, who employed Birnbaum-like appropriation strategies in Dumping Core (1984) and Total Recall (1987). Intercutting pirated images from dozens of TV and film sources with nascent computer graphic work, Bender called these multi-monitor, multi-channel videos “electronic theater.” (For Total Recall, she developed eleven channels of video, transmitted across twenty-four monitors and three projection screens.) Against the corporations that Birnbaum’s videos subtly critique, Bender launched an all-out war. Her videos assault the viewer with a fragmented bombardment of images and sounds, amplifying—rather than simply deconstructing—the violence running through the undercurrent of TV’s relentless river of images.

More than Birnbaum, Bender made ample and direct use of corporate imagery. Total Recall opens with images of ads for General Electric, a company whose slogan during the ’80s, as Bender reminds us, was “We Bring Good Things to Life.” To the average American, General Electric was a multinational conglomerate known for producing consumer goods like refrigerators, air conditioners, and microwaves—appliances designed to preserve food, cool down homes, and otherwise make private family life more comfortable. But in Total Recall, the pastoral images of happy parents and women on horseback that GE used to market its products are soon superseded by images of jet fighters, rocket launchers, and military tanks. For GE was not just in the business of making refrigerators: it was, and still is, a major weapons manufacturer and aerospace contractor. Developed at a particularly fraught moment during the Cold War, Total Recall reminds the viewer—via audio-visual blitz—that happiness in the American home is often made possible by violence abroad.

It seems appropriate, then, that the first video that Bender would record by VCR for artistic use was of news coverage of the 1986 U.S. bombing of Libya, which she had been casually watching while working in her studio. Whether deliberately or unconsciously, critics writing about Bender’s work have framed her artistic project using the language of guerrilla warfare: she was a “hijacker,” an “infiltrator,” a “saboteur,” and, as Cindy Sherman stated in her 1987 BOMB Magazine interview with Bender (quoting a Los Angeles-based critic), a “TV terrorist.” Whereas Birnbaum, as a TV pirate, sought to pilfer individual TV works for her own feminist, anti-capitalist purposes, Bender sought to engage in a televisual act of detournement—to reroute entire networks in an effort to expose the ways TV manipulates the American public en masse by desensitizing us to images of military and corporate malfeasance. To Bender, television networks and telecommunications companies were promulgators of death—she famously compared the striated blue globe that AT&T adopted as its logo in 1984 to the Death Star battle-station in Star Wars. (At the same time, Bender, like Birnbaum, worked in mainstream television and sought to change the system from within—both artists developed content for MTV, and Bender is best known for creating the opening title credits for America’s Most Wanted.)

THIRTY YEARS LATER, online platforms such as Facebook have largely commandeered AT&T’s role in controlling the channels through which far-flung friends and family communicate with one another. The rise of social media has, ostensibly, made the production and circulation of audio-visual material much more democratic—anyone with an iPhone or Android can become a “content creator” by recording and disseminating short videos on platforms such as Facebook, YouTube, or Instagram. Sondra Perry herself has underscored the importance of Tumblr and YouTube to the development of her artistic practice, stating at the February 15 event that the platforms provided integral outlets for her to both share her work and connect with other artists early in her career. And yet, the claim that Birnbaum first put forth in the ’70s—that the media are acting upon us in ways that we cannot fully understand or grasp—is largely still true. Wary of Facebook’s motivations for propelling videos depicting Sandra Bland and Freddie Gray dying at the hands of police to the top of her feed, Perry said that she suspended her account in 2016 because she was “tired of having to encounter images of the death of Black people and not having anything to do with it.” Though the images and videos that appear on social media feeds may have been accessible—and even downloadable—the algorithms that order these images remained out of reach.

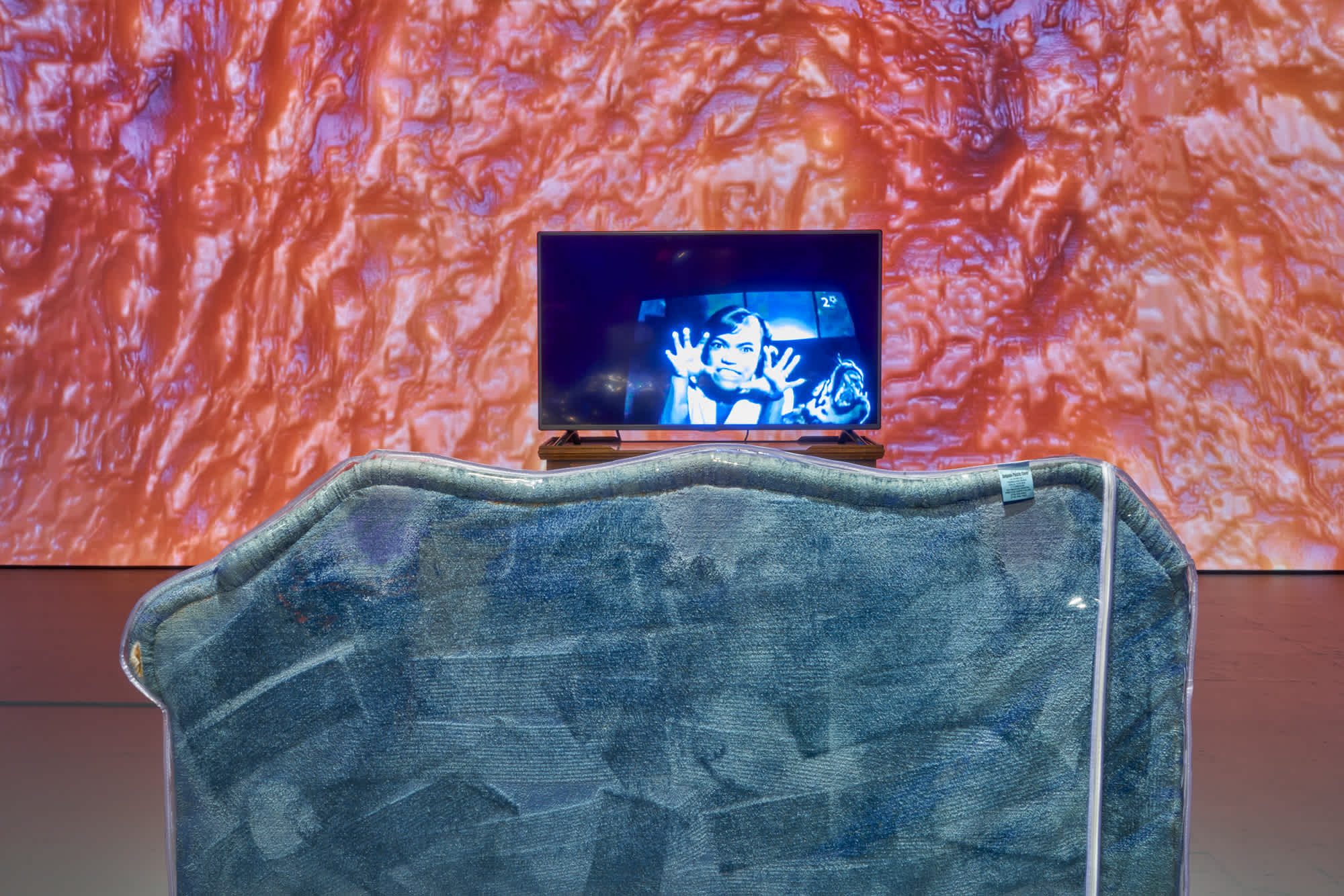

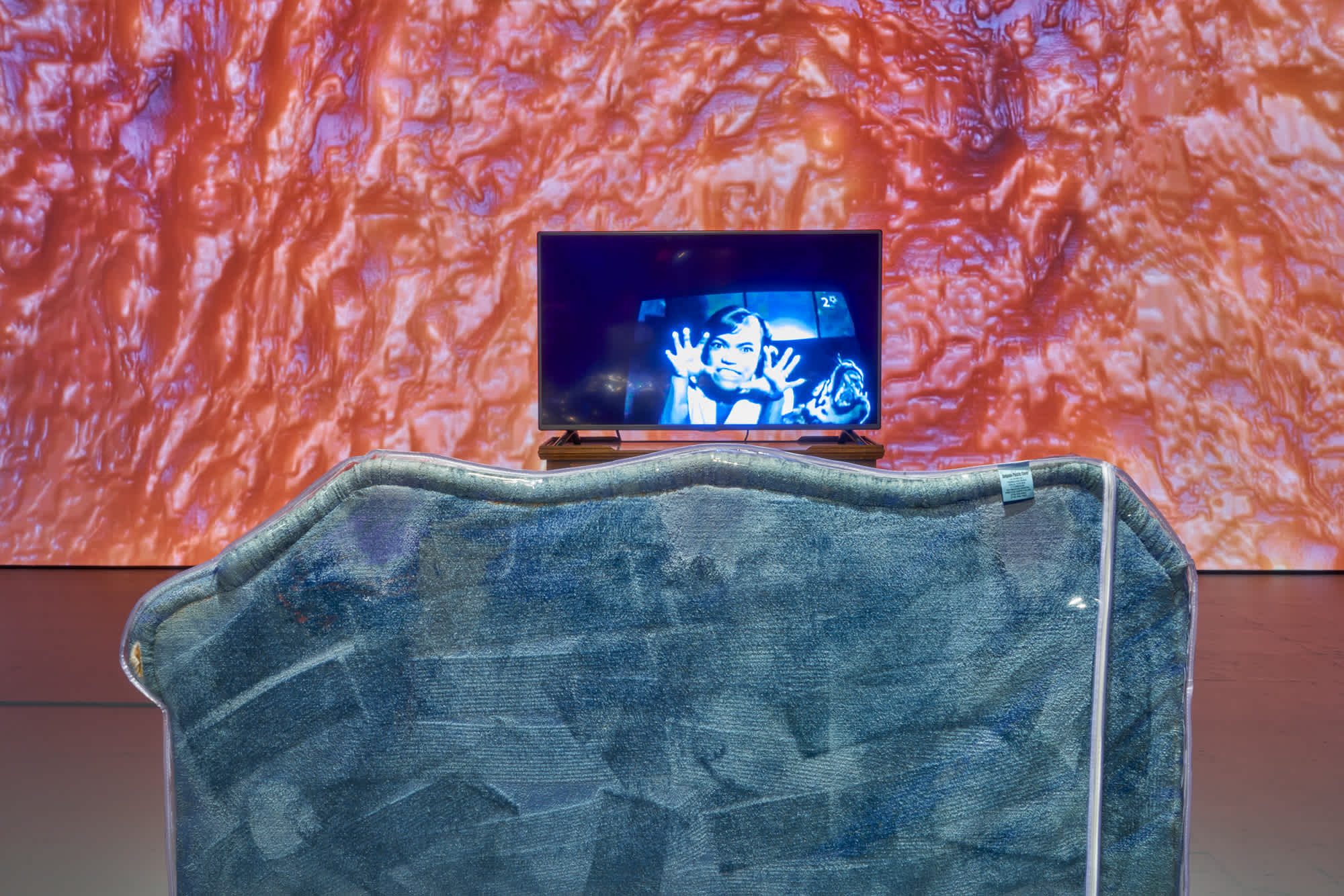

Believing that Facebook was quietly profiting off of images of Black death, Perry developed Resident Evil, a seven-work exhibition that opened the weekend before Donald Trump’s election in November 2016. Videos such as netherrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr 1.0.3 (2016) and the titular Resident Evil (2016) interrogated various media representations of Blackness, depicting images of police raids, Eartha Kitt singing “I Want To Be Evil,” Bill Gates awkwardly dancing, and activist Kwame Rose’s tense encounter with journalist Geraldo Rivera at a protest following Freddie Gray’s funeral in Baltimore. Chroma-key blue walls flanked the main gallery floor on either side, calling to mind the blue screens filmmakers use to superimpose new backgrounds in post-production.

Chroma-key blue is the color of absence, of pure negativity—in the context of a visual art exhibition like Perry’s, it disavows the neutral white cube that so often dominates museum and gallery presentations. Used as a backdrop in netherrr…, the cobalt hue further recalls the “blue wall of silence” that protects police officers from reporting their peers’ misconduct, as well as the “blue screen of death” error message that Windows users receive during fatal operating system errors. But chroma-key blue, because it allows filmmakers and artists to manipulate images after they have been cast, also allows for possibility and regeneration. In Resident Evil, Perry aimed to imagine new value systems outside of white supremacy—and to upend socially held notions about what people, and what acts, should be considered “evil.”

Unlike Birnbaum and Bender, Perry fabricated unique physical conditions for consuming the videos in Resident Evil. While watching a video of Perry’s digitally-rendered avatar discussing a sociological study that determined that Black people who believe that society is “fair” are more likely to suffer from chronic illnesses in Graft and Ash for a Three Monitor Workstation (2016), the viewer could occupy a hard-to-peddle exercise bike. By rendering the exercise bike less functional, Perry disassembles the neoliberal notion that people must tire themselves out physically in order to be healthy and productive—and by tying the bike to a video detailing chronic illness within the African-American community, she also reminds us that white “wellness” culture often comes at the expense of Black exhaustion.

To view another work in the exhibition, Wet and Wavy Looks—Typhon coming on for a Three Monitor Workstation (2016), a gallery goer could sit upon a rowing machine filled with resistant hair gel while watching a video of digitally-rendered ocean waves. Wet and Wavy Looks was inspired by J.M.W. Turner’s painting The Slave Ship (Slavers Throwing overboard the Dead and Dying—Typhoon coming on) (1840), which portrays the African slaves who drowned in the 1781 Zong massacre after the ship’s captain determined that their lives were worth less than the insurance money he would earn from the wreckage. But whereas Turner depicts the shipwreck from a wide angle and seemingly omnipotent perspective, Perry’s video, by depicting only the waves that would have crashed against the shipwrecked bodies, asks the viewer to imagine the massacre from the point-of-view of an individual slave—and in turn challenges the slave trade system that reduced Black bodies to products and mere vehicles for profit.

THOUGH TURNER’S SLAVE SHIP depicts a moment of violent upheaval along the Middle Passage, its action is arrested in painted tableau—the bodies are frozen, the waves static. By contrast, Perry’s video, with its rowing machine and rippling waves, conjures a situation in which its shipwrecked slaves might still be able to move. This movement, of course, requires significant labor. But it is through movement that, Perry implies, Black Americans have been able to combat the malevolent forms of cultural erasure, denigration, and appropriation that have occurred throughout the nation’s history.

Discussing the relationship between Blackness and technology, Perry told Tamar-Clarke Brown in a 2018 interview, “our coming over here was related to our object associations. We were machinery. We were chattel. We were production spaces. But we were also doing a bunch of other types of production: cultural production and spiritual production.” The video works in Resident Evil acknowledge the various spaces—the police station holding cell, the slave trade cargo ship—where Black bodies have been turned into objects, into chattel. But they also extoll the diverse ways that Black artists, as cultural producers, have used the technologies available to them to upend white value systems. In the 1950s, this could take the form of Eartha Kitt clawing knowingly at the camera lens while cheekily singing “I Want To Be Evil.” In the twenty-first century, this movement predominantly takes place online.

Echoing artist and curator Aria Dean, whose essay “Poor Meme, Rich Meme” is included in a zine that a Roomba carried throughout the gallery during the Resident Evil exhibition, Perry has argued that memes—though often generated by Black creators and appropriated by white users—can serve as a particular tool of resistance. Memes, by their very nature, can always be augmented, can always circulate in new ways. Birnbaum and Bender, too, saw political potential in such forward-looking slipperiness. Bender, for instance, stole the title Total Recall from a magazine listing of movies that had not yet been released. And Birnbaum’s Technology/Transformation, though highly critical of Wonder Woman’s commodification, still avowed the character’s ability to transform—to spin off screen and slip through the fingers of the men who attempted to hold her.