Credits:

By Sherry Tseng, Winter/Spring 2021 Curatorial Intern

July 2, 2021

“From the Archives” is a series that spotlights The Kitchen’s history. As a complement to our Archive Website, these posts offer focused reflections on the artists, exhibitions, events, and institutional practices that have defined and shaped The Kitchen since its founding in 1971.

FROM MARCH 16–20, 1976, The Kitchen presented an exhibition of Barcelona-born multimedia artist Antoni Muntadas’s video installation titled The Last Ten Minutes. The piece was part of “Accion/Situacion: Hoy. Proyecto A Través Latinoamérica,” a larger constellation of Muntadas’s works that explored the symbiosis between art and life in relation to the public and the private. As the press release for the exhibition noted, this work reflected a gradual progression in Muntadas’s practice, moving away from interests in the role of sensory perception and toward inquiries into human communication phenomena across different mediums. While parsing through The Kitchen’s archival material, I found myself drawn to the presentation of The Last Ten Minutes, its meaning as it was exhibited at The Kitchen, and its significance today.

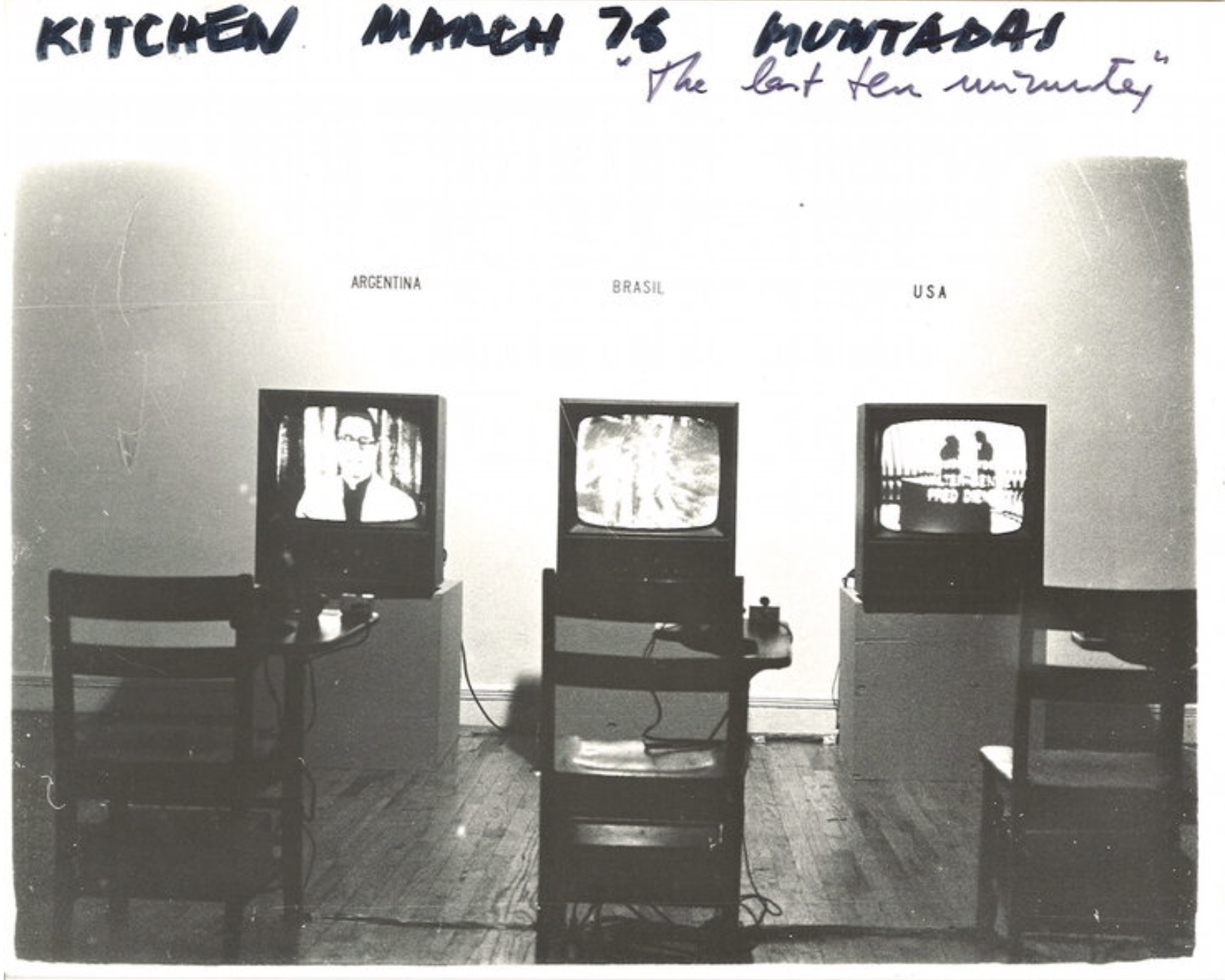

The Last Ten Minutes is a three-channel video installation with three identical chairs positioned before three identical monitors. On the wall behind, each monitor is labeled with the name of a country: Argentina, Brasil, or USA. These labels correspond to the contents played on each monitor: the last ten minutes of a playback of late-night broadcast television in the respective cities of Buenos Aires, São Paulo, and New York. Following this is footage of actual urban street scenes and people from the corresponding site. In this setup, Muntadas underscores the similarities of mass media culture in the three countries. In each, there is a similar presentation of breaking news, a similar posturing of the broadcast news reporter, and a similar use of corporate signage. However, the subsequent imagery of the urban street scenes reveals the glaring contrast between the homogeneity of a mass media society and the heterogeneity of its individuals and cultures.

As presented, the video installation speaks to the subjectivity of objectivity, in that a seemingly one-dimensional experience obscures its actual form as a kaleidoscope of vantage points. This is the contradiction in our communicative forms that Muntadas poses in The Last Ten Minutes: mass-produced visual culture, under the guise of a homogenized oneness and singularity, is actually a product of its contextualization and historicization, as well as a sounding board for a reality mediated by our psychologies.

At the time of its creation, The Last Ten Minutes was influenced in no small part by Muntadas’s own experience with the way the media could be exploited to manipulate the public. Having lived under General Francisco Franco’s military dictatorship in Spain, Muntadas had first-hand experience of authoritarian rule and a familiarity with censorship of any public display, symbols, or signage of liberal political ideology. As such, during a time age in which the very nature of information and truth was up for debate, disagreement over the constitutions of realities fueled perceptions of disjunctive ontologies, such that reality bifurcated into one imposed by ecosystems of propaganda and censorship and another obscured by said ecosystems. In turn, the multiplicity of realities under Francoist Spain (as is the case under most totalitarian regimes) then acted reflexively to set in motion a self-fulfilling prophecy. Perception of different realities was cause for different realities. Today, nearly half a century later, the same holds true, as is evident in the increased misinformation and disinformation in our current cable news network landscape. On this account, I take The Last Ten Minutes to be a piece that allows us to better understand the questions that beset us today. In a similar vein, when applied to our current moment, the work’s diagnosis also suggests a remedy that carves out a path for an alternative future. Thus, in re-examining this installation, I hope to trace a path of continuity—and of change—between our present and future.

IN BEGINNING TO UNDERSTAND THE LAST TEN MINUTES, we are confronted by these preliminary questions: how does Muntadas understand the role of art and visual culture in a mass media society? How are we to understand the role of art and visual culture in a mass media society? In sifting through The Kitchen’s archival material on The Last Ten Minutes, two immediate thoughts jump into focus.

On one view, the claim that technology and mass media bear pernicious implications is a well-rehearsed one. In particular, the installation draws into view the concept of technological rationality, as theorized by philosopher Herbert Marcuse. To briefly summarize, technological rationality is the idea that the pervasion of technology into society can fundamentally alter constructs of reason and rationality. In the case of The Last Ten Minutes, the arrangement of the work is such that the viewers participate in an experience that has been scaffolded on a predetermined logic—the logic set by technology. To be more specific, as the audience views the installation, they are prompted to sit in a chair (identical to all other chairs) placed before a monitor (also identical to all other monitors). By doing so, their physical selves necessarily inhabit a trite and homogenous reality—one characteristic of mass media culture conditioned by the technological form. Thus, even while viewing the footage of urban street scenes that serves as a mechanism for critiquing the homogeneity of the commodified mass media culture, the audience members are physically partaking in a phenomenological experience grounded in said mass media culture. As such, the experience of the juxtaposition is itself structured by the terms of mass media, lending to the totalitarianism of technology in molding both our conceptions of rationalities and our capacities for rationality.

Yet a second interpretation undercuts the cynical view proffered by technological rationality. This reading suggests that rather than technology and mass media upholding a logic of their own that is subsequently coerced upon individuals and societies, the visual culture contained within mass media is a convergence point for the diversity of human culture. Instead of serving as a top-down authority that dictates the logic of rationality, mass media is a reflection and synthesis of a grassroots consciousness and a common ground that threads all of us together in spite of all our differences. In its own banality, it finds the shared pulse of a collective sociology.

On this view, the imagery played in The Last Ten Minutes of late-night broadcast television is not to be understood as a totalitarian hegemon. Rather, those last ten minutes, as well as the subsequent footage of urban street scenes, introduces the possibility of an alternative: a non-place. Located in a non-place, the images and their contents are deterritorialized, demilitarized, and neutralized. In viewing the piece and being whisked into a chair (again, identical to all other chairs) placed before a monitor (also, again, identical to all other monitors), the viewers are freed from their geopolitical specificity. The fact that the viewers are able to roughly comprehend those last ten minutes as playback of late-night broadcast television, irrespective of the country of origin, is owed to the similar presentation of breaking news, a similar posturing of the broadcast news reporter, and a similar use of corporate signage. Such is similarly true of their own embodiments: that their physical selves are placed into this homogenising reality rids them of what biased exceptionalism may exist and instead reminds them of their common humanity.

This interpretation of Muntadas’s The Last Ten Minutes as a confluence of all of us is further maintained by its very presentation in The Kitchen. At the time of installation, The Kitchen had been operating for three years out of a space on the second floor of the LoGiudice Gallery in Soho at the corner of Wooster and Broome Streets (it moved from its first home in the Mercer Arts Center in 1973). As a venue for the avant-garde and the experimental, the exhibition and performance space was then gaining international recognition. I see the setting as an extended metaphor of the work: just as The Last Ten Minutes shows the ways in which the reproduced homogeneity of mass media culture may serve as a form of reprieve for viewers, audience members may find familiarity in the common thread of experimentation as cultivated by its own deterritorialization within a singular space such as The Kitchen.

I offer both these views because, as Muntadas shows, the two can be reconciled, if they are not already one and the same. In fact, the larger picture to be drawn out is that what makes The Last Ten Minutes a cautionary tale for the pitfalls of technological rationality is precisely also what makes it present as a non-place. In this vein, which of the two interpretations the viewers are to understand the piece by is contingent on the description of where we are and where we can go. The interpretation as technological rationality is the path of continuity between our past and present, and its interpretation as a non-place is that of change between our present and future. The piece is then an admonition and a beacon of hope in equal measure.

FOLLOWING THE EXHIBITION AT THE KITCHEN, Muntadas presented a second part of The Last Ten Minutes in 1977 at Documenta 6, an exhibition in Kassel, Germany that explored the role of art in a mass media society. The Last Ten Minutes II is a replica of its first iteration, though it instead features the three cities of Washington (USA), Moscow (then the Soviet Union), and Kassel (Germany). Installed at a time when relations between the two superpowers of the USA and the Soviet Union were deteriorating, with Germany caught in the middle, the piece again pressed the point of simultaneous similarity and difference between the three countries. All three were embroiled in the mass media society, yet each held their own distinct realities on the ground, as reflected in the footage of the urban street scenes.

Ultimately, this pair of installations set the stage for Muntadas’s later work in the project “Accion/Situacion: Hoy. Proyecto A Través Latinoamérica” and beyond. As described in the press release for The Last Ten Minutes at The Kitchen, “the realization of these works as a model, the analysis and comparison of behavior from different cultures and the relationships among anthropology, psychology and sociology are constant in the works of Antonio Muntadas in his latest works.” In 1980, Muntadas exhibited a second piece at The Kitchen titled Personal/Public (1979) as an installation in the gallery (a presentation of three additional videos took place concurrently in the Video Viewing Room). As written in the press release, Personal/Public “focuses on the intersection where personal information is rendered public by the media and public information becomes personal by individual interpretation.” The work was a two-channel video installation: one monitor screened a medley of entertainment forms, such as soap operas, while the other monitor played footage of the viewer as captured on a hidden camera. The piece was aimed at foregrounding said intersection. Similar to The Last Ten Minutes, it draws attention to the blurred lines—made hazy because of their conflations—between natural and artificially constructed realities.

Decades after the creation of these works, as I look through the archives, the message behind The Last Ten Minutes speaks just as loud, if not louder. Media outlets today contribute to the amplification of a politics of identity that reproduces and exacerbates undesirable material conditions. As hard facts, such as those today on a pandemic, climate change, and racism, lose their positions as hard facts, the likes of public health, the environment, and social equality are denigrated in status to mere academic endeavors, thus stalling and obstructing the prospects for real, practical, and tangible change. All this is in part the result of a mass media culture, but as Muntadas himself challenges, there is potentially hope to be found in the non-place of our visual culture. Perhaps with the deterritorialization of our images, the politics of identity may well dissipate. And as we move forward, The Last Ten Minutes may serve as an example against which we fashion the first ten minutes of an alternative future.