Credits:

By Noa Rui-Piin Weiss, Summer 2021 Curatorial Intern

September 16, 2021

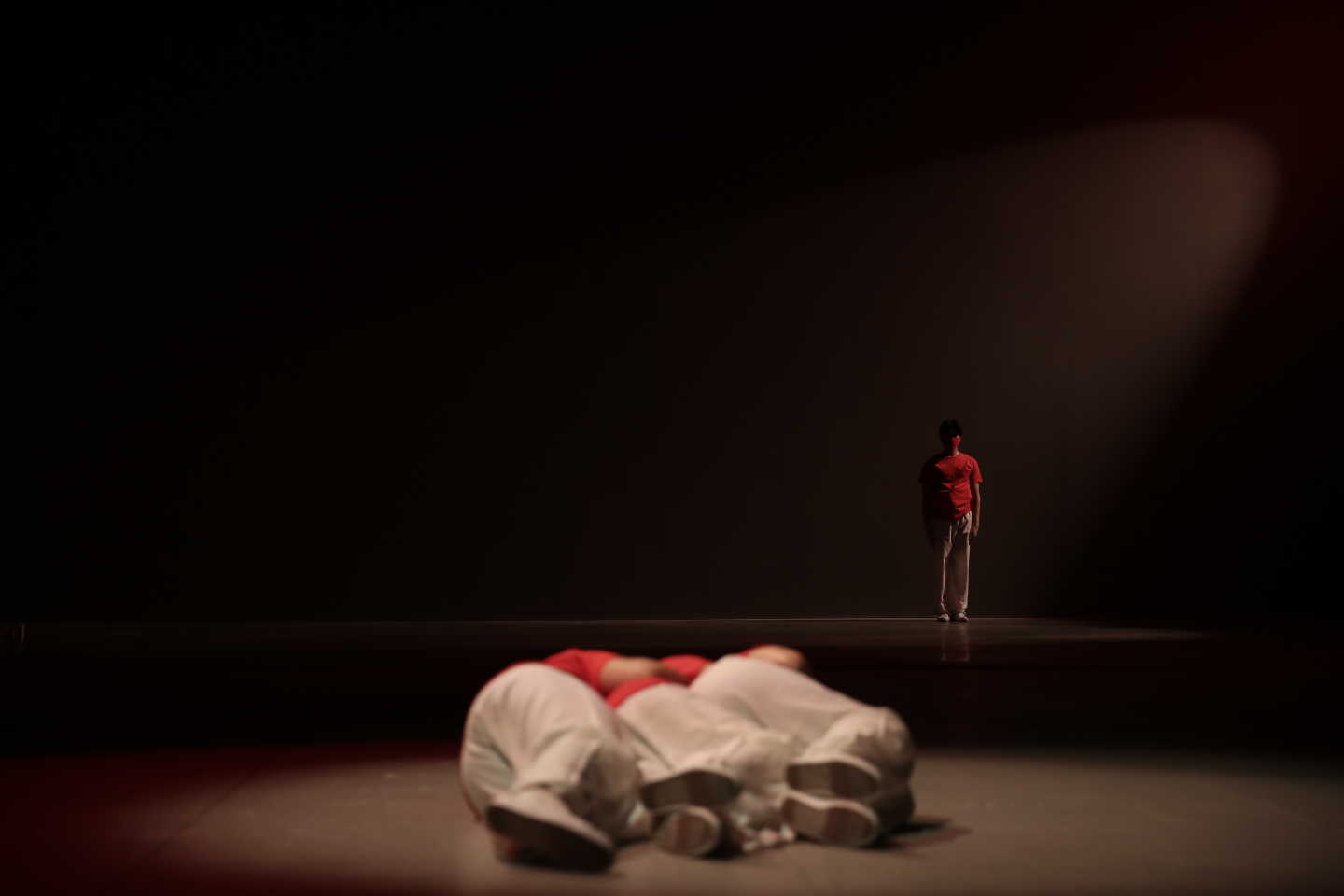

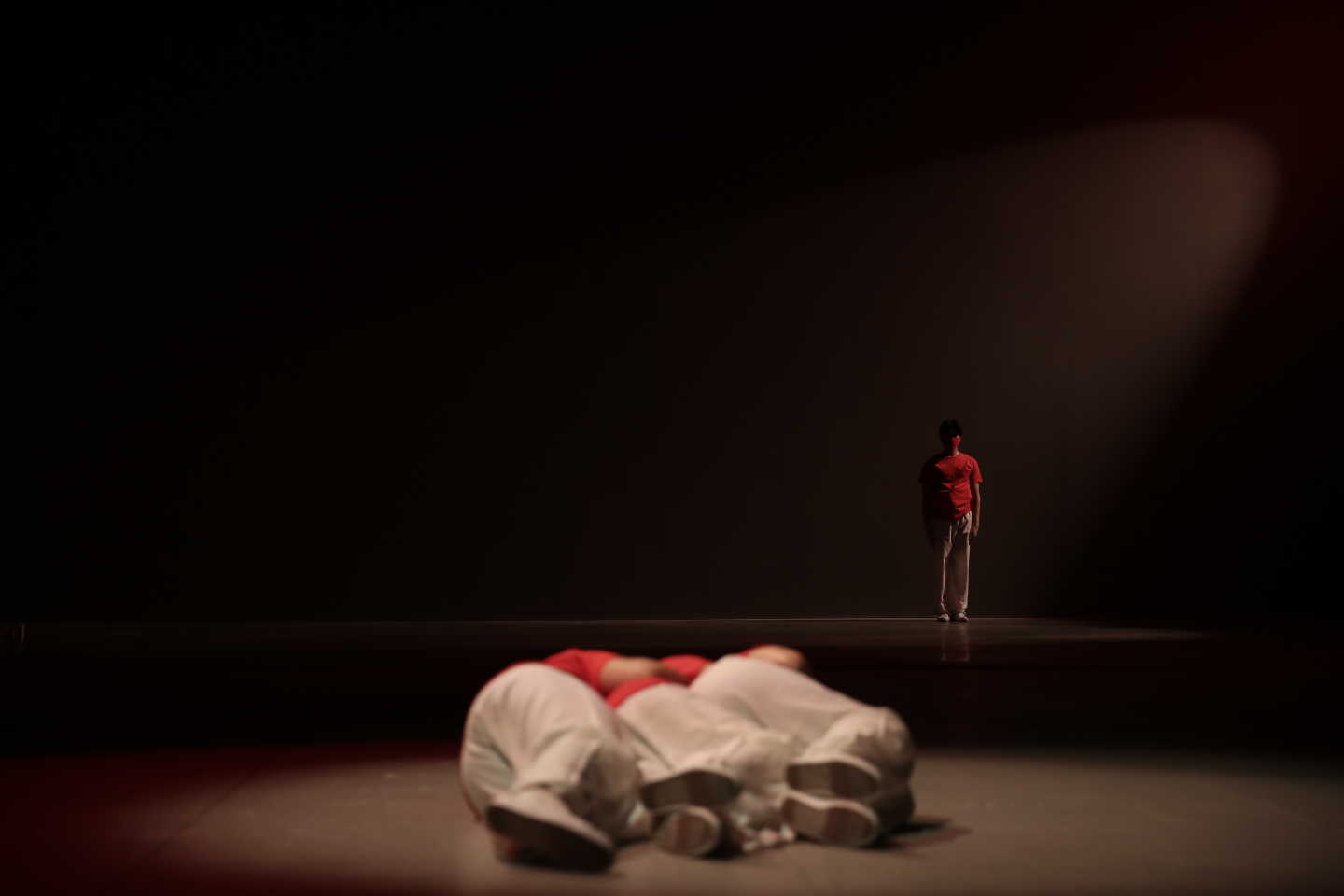

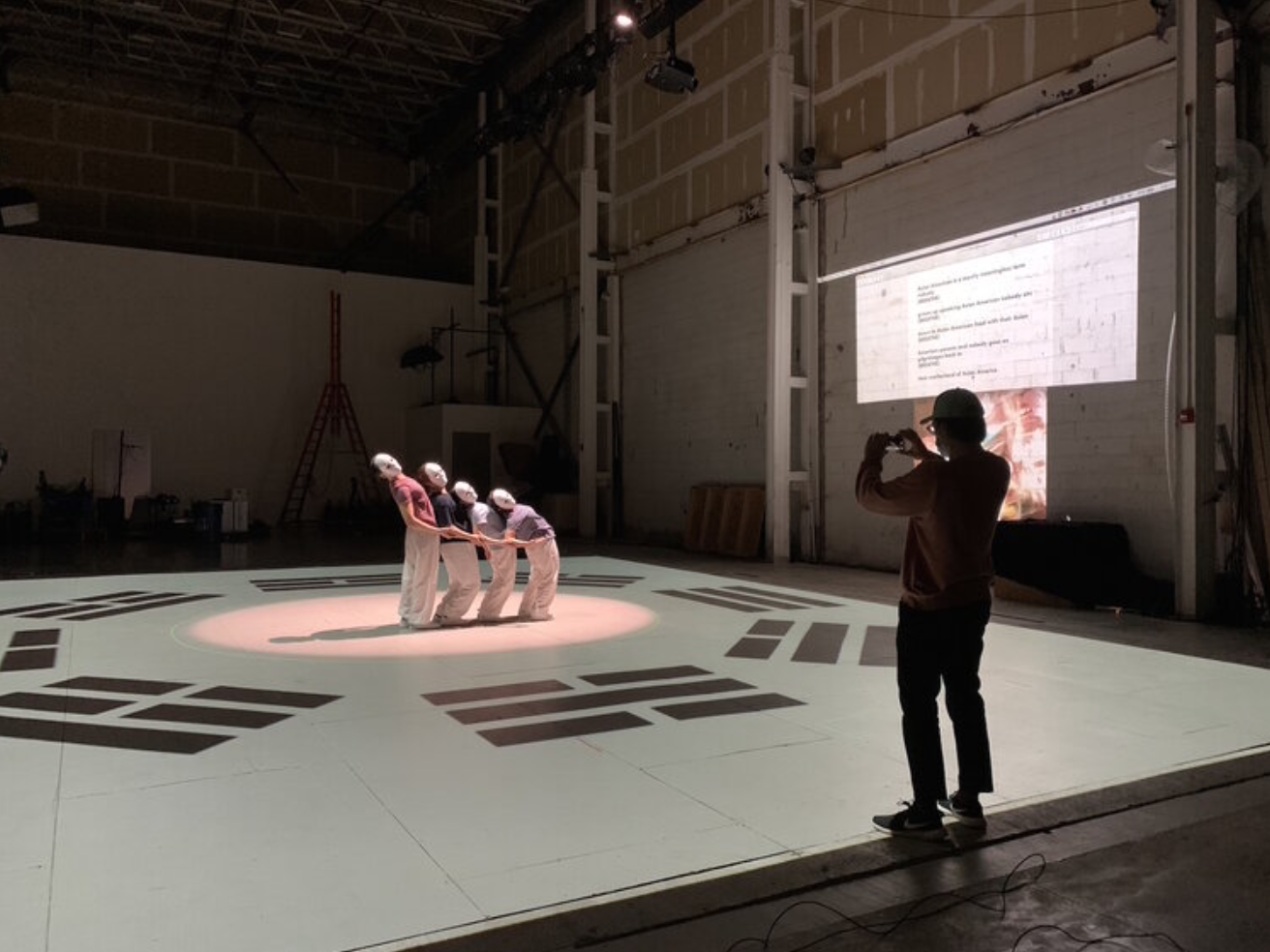

Kenneth Tam was in residence through The Kitchen at Queenslab from October 30–December 6, 2020. The residency culminated in the performance The Crossing, which premiered via livestream on December 5 and 6. After the stream, Senior Curator Lumi Tan hosted a post-show conversation with the artist about the piece, which is available via OnScreen.

Kenneth Tam has been artistically invested in men’s social spaces for years, exposing themes that have floated unnamed through national conversations. His work follows men’s behavior and points out the patterns that exist at the intersections of race and social intimacy. Tam’s projects engage with the reality that America’s masculinity crisis is ongoing, and Asian American men are not exempt. The fracturing Asian American political movement, the NYU Lambda suspensions for racist messages, the plot of Minari—these trending topics are all haunted by the specter of men and masculinity. Asian American men are struggling to define themselves in a society that shies from interrogating either identity, and Tam is listening.

The Crossing does not provide an answer for lost men. Tam is more interested in the cultural and historical reasons why Asian American men can feel adrift, and exhibiting what they do about it. The interview below was conducted via email in late July 2021.

What draws you to masculinity / why have you remained dedicated to it?

Lately, I've been feeling that the word “masculinity” is not really the most accurate way to describe what I’m drawn to in my projects. I think that word certainly is relevant and is a helpful shorthand for a number of related ideas, but I feel I’m more interested in looking at how men create intimacy, and the different ways the body is activated within those moments and spaces. While tied to masculinity, I’m more drawn to the affective spaces created by men in groups, and the tender yet awkward beauty that can be found in those spaces.

How did you consider the role of sexuality in The Crossing (considering the fear of homosexuality built into traditional conceptions of masculinity, and the heterosexuality implicit in the fraternity/sorority system)?

While sexuality was not something I made explicit within the performance, I did think about the fraternity as a homosocial space, one where that intensity of male affect which might be otherwise described as simply “bonding” has the potential to become something neither queer nor straight. With that in mind, I also recognize some of the ways in which these spaces can be very queer. For example, the activities involved in hazing often seem like elaborate rituals designed to allow men to touch one another, or the ways in which the intense policing of queer behavior can create the kinds of tensions that lead to that very outcome.

How did you envision the interplay between the historically male gaze of the camera and the medium of live performance? How did you think about these questions in relation to the livestreamed, filmed format of the piece (which was a necessary alternative to live performance due to COVID restrictions)?

To be honest, I’m not sure I would subscribe to the idea that the camera can only offer a male gaze that objectifies its subjects—surely there are different modalities of desire that are being produced through a lens that don’t specifically conform to a male subject? In re-imagining The Crossing as a livestreamed event, I was much more concerned about the question of how liveness was going to be understood and felt to an audience at home; how to distinguish the performance from something that might have been recorded and later re-broadcast. The stream was meant to convey the documentation of a live performance, and not meant to be understood as an artwork itself.

Probate rituals often mark the first time young men have to memorize and perform choreography. How was your choice to use trained dancers influenced by the untrained performances by frat members?

I actually think that while the frat members might be amateurs, the sheer complexity of some of the probates, which are a combination of long, memorized texts and choreographed movement, is itself notable and probably would be challenging even for those with training. My decision to use trained dancers came about more from a pragmatic need to work with people who knew how to move their bodies, and could memorize and execute the performance I was trying to create. I also knew that I would need their input on the basics of building choreography, as this was my first attempt creating a scripted performance.

To what extent does the appropriation of Black fraternal traditions by Asian American frats reflect on the intersections of these masculinities?

I think this borrowing speaks to a genuine appreciation for the creativity and flamboyance that Black probates generally display, but on a deeper level there is a sense of identification with the struggles of one group by another. The creation and proliferation of multicultural Greek organizations is heavily influenced by the history of Black Greek life, specifically in the latter’s desire to create spaces of belonging in majority-white college campuses that were often hostile to Black bodies. However, the struggles experienced by Black students and their Asian American counterparts are not the same, and the way certain traditions like the probate are performed differently might speak to that difference. For example, Black probates often place a much greater emphasis on the performance of hypermasculinity and toughness, whereas the Asian version feels more playful and even lighthearted and self-effacing.

You were already dealing with the diffuse nature of Asian American identity in this piece (e.g. the Jay Caspian Kang quotation from the New York Times), but this conversation resurfaced with the rise of the #StopAsianHate movement. Where do you find the term “Asian American” being useful? Where is it not useful?

I think like any racial category, particularly in this country, its usefulness runs the risk of eliding complexity and nuance. This was one reason I referenced the Kang article in the performance, mainly through the idea that the term Asian American is a kind of fiction that relies on those who fall under its umbrella believing in its value in order to give it actual meaning. Because it is a relatively recent invention, Asian American is an idea whose meaning is reified everytime it is invoked—what it refers to is constantly being renegotiated. So I think it functions best as a political term that different groups can coalesce around and find shared meaning in. But its coherence starts to fray at the edges where it’s no longer clear who “Asian-American” is referring to, when one realizes that casting such a wide net might be creating affiliations where none exist, and worse can erase and invisibilize different histories and struggles.

What kind of message would you want this piece to convey to a member of an Asian American frat? What questions would you want to ask a brother?

The questions I tried to pose with The Crossing revolved around the contradictions I felt these fraternities' traditions embodied: Why the need to come together to create Asian identity while deliberately borrowing from non-Asian sources? Why is physical violence necessary to facilitate the desire for male intimacy? And perhaps the more overarching question is how much of cultural identity is itself a necessary fiction in order to create meaning for its members, and how far will people go to pursue or maintain these narratives?

A lot of the art discourse I see focuses on diaspora: people earnestly honoring cultural traditions in high art settings. The Crossing intentionally plays fast and loose with the concept of tradition. Is this the new diaspora? Is it time to retire this idea of “authentic” or “historically accurate” relationships to cultural lineage in the Asian-American experience?

I wouldn’t presume to tell people what they should or shouldn’t believe in, especially as it pertains to their identity as diasporic subjects. So much of being a part of a diaspora is tied to loss and trauma, so the need for authenticity is a powerful and deeply centering force. With that said, I also feel that as an artist, my natural inclination is to be skeptical of any possible meta-narrative that might dictate who we are, or who we think we are. Part of what is so interesting about being a diasporic subject is the ability to see identity as contingent and multivalent, acting less like an anchor tethering someone in place. I see identity as more like being in the confluence of multiple bodies of water, where trying to find the source for something is rendered moot. It’s also important to recognize the many layers of cultural identity in Asia, with histories that often tie people to local villages instead of to entire nation-states. To even claim one’s identity as unequivocally Chinese, Indian, etc. only invites many more questions that might destabilize those very identifications. So while I would not advocate for the wholesale retirement of the search for “authentic” cultural expression, I would like to see artists continue to complicate notions of identity, treating the subject with less orthodox reverence and seeing it as layered and sedimented through movement and history.

The Crossing was Tam’s first piece made in collaboration with trained dancers. As a dancer myself, I wanted to hear the performer’s perspectives on the work, as well as their own conceptions of Asian American identity and masculinity. I posed the following question to cast members Paulina Meneses and Resa Mishina: How did your own experience of Asian American identity relate to the portrait of Asian American fraternities you were painting in this piece? What is your relationship to masculinity?

Paulina Meneses: The portrait we were painting about Asian American fraternities related to my own experience of trying to conform. My understanding of these fraternities is that you aren't necessarily an individual, but a puzzle piece to the collective and you must be on the same page as everyone else. Growing up I felt the need to fit in with specifically two groups of people. My friends from dance, who mostly consisted of white upper-middle-class people, and my family friends who mostly consisted of lower-middle-class Asian Americans. I always felt the need to act a certain way with each group rather than being myself with whomever I was with.

Resa Mishina: I’m an immigrant from Japan, so I did not have the Asian American experience growing up. However, I definitely felt the otherness of being a minority once I came to America. The performing arts community in New York is small but the Asian artist community is even smaller. Whenever I see a fellow Asian performer, even if it is the first time meeting them, I know that we share the same thoughts and experiences: the microaggressions, the constant doubt of your talent and value based on your skin color, the unspoken rule of being the token Asian figure in an ensemble. Because of these shared experiences, I feel that I can connect with fellow Asian artists on a deeper level compared to my white colleagues. I think that’s similar to what members of Asian American fraternities feel.