Credits:

By Alexis Jacquet, Fall 2021/Winter 2022 Curatorial Intern

Transcribed by Susana Plotts-Pineda, Spring 2022 Curatorial Intern

Edited by Sienna Fekete, 2021-22 Curatorial Fellow

May 10, 2022

E. Jane’s first solo institutional exhibition Where there’s love overflowing is on view at The Kitchen through May 14, 2022. While the artist was installing their work, Curatorial Intern Alexis Jacquet spoke with them about the intersection of art and music and the research behind the new pieces created for this exhibition. In the conversation below, they get into the legacy of Black femmes in the music industry, how history informs the work of music covers, the realities of working as both visual and performing artist, and the power of love.

Where there’s love overflowing features a variety of work including digital drawings, gouache wall paintings, and sculptural video installation surrounding a central, empty stage. These works draw upon the artist’s archive of performances of the powerful ballad “Home,” originally sung by Stephanie Mills as Dorothy in The Wiz in its Broadway premiere in 1975. The exhibition encompasses a residency for a culminating performance event by MHYSA, RaFia, and PrieSTusSSY, with Musical Direction by Kyron EL on May 14 at 7 pm. The artist will hold performance rehearsals each day from May 10–13 from 2–6 pm. During this time, the exhibition will be closed to the public, but visitors will be invited to eavesdrop from the lobby.

Alexis Jacquet: I was curious about how you balance your personas MHYSA and E. in one head. Does that ever get confusing?

E. Jane: No, I guess because I have a really great mentor who gave me really good advice when I was in graduate school. Sharon Hayes would just be like, it's all coming from your body, you know? And I think because she has a background in performance and theater, she just really processes how personas work. But it’s definitely something I think about. Like, when actors talk about a character they’ve created, or that they’ve been playing for a long time, and they’ll just use Method acting to talk about them. It’s kind of like she [MHYSA] is of my body. It’s like it’s a part of myself that I could compartmentalize and put away and then pull out later. And so it just feels like we’re both active participants.

One of your many collaborators?

Yeah.

That’s beautiful. That brings me to my next question. Where have you envisioned the aim of your research into the Black femme divas heading within this kind of relationship with personas?

I guess I don’t think about it that way. I’m asking questions. I use the project to allow me a space where I can ask questions, where I can do field research and where I can just have the space to actually perform. The research comes up as I’m working. There is no endpoint, there’s no place to go. It’s kind of about the process. It’s not a journey towards something, it’s just a journey. It’s about the process as you’re going along,more so than an endpoint.

It makes me think about road trips, and the sense that it’s never the destination that’s necessarily the aim, but the journey, and the memories you’re making and what you’re finding along that way.

I’m thinking through embodiment, but I’m also thinking through history. I think I was talking to Lumi [Tan] about the fact that I feel like any vocalist worth their salt knows a lot about their genre—any musician really knows a ton of music history, and has a ton of opinions about musicians that came before them, and musicians around them in the field. Whenever I talk to musicians, they always have so many opinions about new music, about old music, can tell you how many notes a certain singer can hit [etc.] So it’s like in some ways, this project argues for something that is already true, art happening in music spaces. Ayanna Dozier has a really great book on Janet Jackson that she wrote for the 33 1/3 series. In it, she talks about Janet Jackson being an audiovisual artist because of her work with music videos and with her tour staging. She talks often about Janet co-collaborating with people, and basically sharing a vision. I think that’s why I started looking at albums from an art perspective. One of my favorite albums to bring up is this Diana Ross album [Silk Electric (1982)] that Andy Warhol did the cover for.

Oh!

Yeah, so there’s already been a lot of art happening in these spaces. They understand clearly. Diana understood contemporary art, or at least her team did. I think performance is the place to flesh those things out, and think about them in the art realm. I guess like, give space to people that always already are thinking artistically, but maybe aren’t seen that way because of these bifurcations between art and music that are mildly arbitrary. Like Milford Graves was calling himself a musician-artist in the 1960s and 1970s.

Why have you gravitated towards doing covers of songs?

I’d say I have an equal mix of both, but generally people cover songs because it’s a way to learn about music, right? It’s a way to study music. It’s a way to touch things that you feel connected to. For example, “Home” is just this really beautiful song that makes me kind of want to cry. It’s so sweet. To touch that with your mouth and your body is really precious. Sort of like, make it your own or interpret it. This exhibition is kind of about that. The show is about a series of covers, right? The original and then the covers, and how everyone interprets and changes lyrics and all these things to bring new meaning to the song, or find connecting points with people from history. It’s important work. I write my own songs, too. I think it’s funny because as time goes on, I’ve been told, you can’t really do covers after a certain point because of property rights. As you get bigger, you kind of have to stop, or you can only put them in your live show. Even when I see someone do a cover in a live show, it tells me a bit about the performer. It tells me about what they know, what they listen to. You know, how they see things.

Maybe we should have a little bit more patience for the divas in our lives. Being a Black femme definitely heightens that because the misogynoir, or the expectation of being superhuman, rubs up against it.

I feel you have had both perspectives of being an admirer of artists and celebrities and after slowly transitioning through MHYSA, becoming the one actually on the stage. What is your impression of that set up?

There’s something about the stage that makes people forget that performers are human in some ways—it’s maybe something that performers rely on. There’s a bit of smoke and mirrors happening when setting someone up on a stage: it makes them feel taller and larger than life, which can be really great. Although, I do love a punk show where someone gets on the ground. It’s a weird relationship, and I appreciate when people can understand. For example, I remember a few years ago on social media, Beyoncé had to announce that she was canceling a show. One of the comments under the post was like, “her voice did sound really hoarse at that last show” and I was like, wow, like damn, clearly, she’s tired.” That’s so cruel! I think there’s something where people forget that there’s labor involved, right? I think that’s the point of the eavesdropping outside the exhibition as part of the rehearsal process for the closing day performance, and the gesture I did at PS1 in This Longing Vessel where you could watch these choreography sessions. I’m very invested in people processing that even if someone is super talented, there’s a lot of labor that goes into talent. Maybe we should have a little bit more patience for the divas in our lives. Being a Black femme definitely heightens that because the misogynoir, or the expectation of being superhuman, rubs up against it. People are pushed beyond their capacities. Even with vocals— the vocal cords are very sensitive things. My vocal coach is just like, you need to see an ENT[ear, nose, and throat doctor] to make sure everything’s OK. There’s also this pressure like…I want to hit a high C! I want to sing really high. I want to show range really badly. A lot of people damaged their voices by doing that. Like Whitney, there’s a specific tour—I think it was in the late ’90s—where basically her voice was shot the whole tour. That was because of all the acrobatics she was expected to show every single night. I remember in one of the documentaries— I think it's Can I Be Me (2017)— they talk about how they had to keep lowering the register of the song so that she could actually sing it. Then there’s that final tour where her voice is just completely gone, and people are not happy. But it’s like, who can be expected to be that perfect for so long, and do that amount of dynamics? Her range is super vast, and she’s always demonstrating it. It’s understanding that when you hear someone like that, you know they are doing a ton of labor. It’s not just this easy thing where you wake up, you push a button, and you’re just like going for it. I wish people understood that being on a stage doesn’t really make you that much different from the person that’s not on the stage. I think that record companies want you to think that there’s this big difference because if you didn’t think someone was larger than life or bigger than you, would you support the project? Even though plenty of people support musicians that they know are just like them. I have a lot of thoughts about this, and not many conclusions.

I mean, especially with the current state of pop culture and more everyday people becoming idols in a sense, there is still a lot of open-ended, unanswered-ness to this all. What would you want people who are in the crowds to understand more about the work that goes into the performance and presenting a piece to the stage for a show?

I think labor is a big part, and encompasses so much of what’s happening. I think it is a really important thing that we haven’t quite gotten past yet. I’m a big advocate of Black women’s labor being respected and valued.

As it should be! What made you gravitate toward “Where there's love overflowing” for your exhibition?

The title or the work?

The title and the work. I know it’s one of the lyrics in “Home.”

Yeah, it’s one of the lines in “Home,” and it also speaks to my goal in doing archival research. I wrote a manifesto [ “NOPE (a manifesto)”], and one of the things I said in the manifesto was that we need a culture that loves us. I was talking to Lumi [Tan] about how I’ve been basically looking through the archive to find culture that loves us. And that culture is Black people being humans and having feelings. “Home” was just the song: it’s about people. It’s about existential crises, which is a trauma that I think Black people don’t get to address enough. You know, what person isn’t like, where am I going in life? What am I doing? I’m getting older, and what does that mean? Even the fact that they’re just talking about the rain and these ambient shots that make you think of anime scenes where you see really cute fields, and you’re just vibing. These images that have everything to do with the human experience. I’m not necessarily hankering for universalism, but in some way it’s just an existential moment of trying to find one’s place in the world that [maybe] has nothing to do with it being harder for you to find your place and be. Written by Black people for Black people. It’s a great thing to me that I think should be cherished. The show is talking about the archive as a space to find love overflowing.

Do you find art, and the artists you gravitate toward, have a certain way of being, and that’s why you gravitate toward them more? How are you finding your sources?

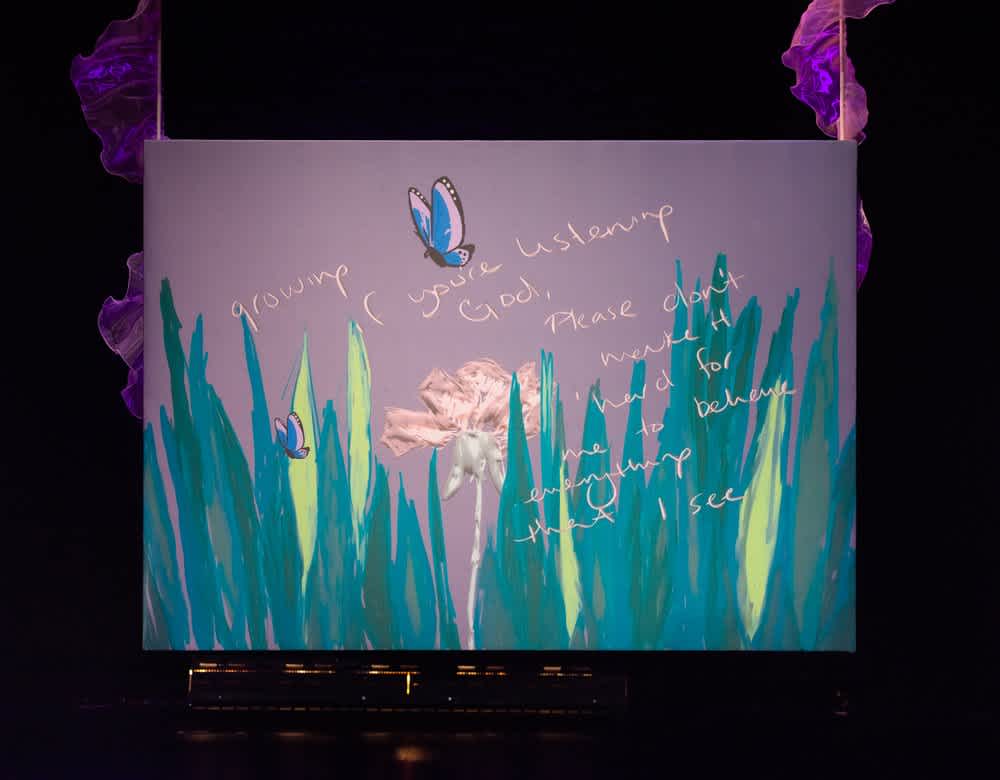

This archive starts with Stephanie [Mills] and then goes to Diana [Ross] and then obviously had to address Whitney [Houston] because her version is so iconic. It’s basically all iconic versions of the song. The other two on the list are Beyoncé and Jazmine Sullivan, because these are versions that they did when they were kids, and versions that solidified their talent. People look at these tapes and see this person was always going to be big because look at them doing the song, trying to live up to this giant legacy. I’ve put them in conversation with one another—the dates are kind of perfect. Even though Stephanie Mills’s version at the Apollo is not on the wall [as seen in Where there’s love overflowing with a musical, archival timeline painted onto the wall], it deeply informs the work and will be involved in its own way. Basically, she did that the year before Beyoncé sang her version, and Beyoncé’s version is very much dependent on the version that Stephanie Mills sang at the Apollo. It’s definitely like trying to live up to that. And then Jazmine Sullivan is just doing her own thing. She’s like, run queen! She’s going up and down the scale like no one else is. No one else’s version is like Jazmine Sullivan’s version. And she’s showing that at such a young age, she has such a mastery of the scale and running up and down it, very smoothly. And everyone’s just kind of blown away. I think that it’s just so interesting to think about Black people performing this Black standard written by Black people to prove themselves—the way people think about that in relation to like, you know, at some point SWV’s “Weak.” Everybody was singing SWV’s “Weak” to prove they could sing. “Home” is also one of those songs. It’s interesting seeing how people perform it differently. I like seeing how they’re touching the material, and how they’re making it their own. Whitney’s version, for example, is very religious because she’s Cissy Houston’s baby, so it had to be. And so there’s a part in the song where it says, “If you’re listening, God,” but Whitney changed it to “I know you’re listening God,” because she can’t question God. Stuff like that is really interesting because it also tells you a bit about their biography, and who they are as performers. That’s why I’m thinking about them. Also, because they’re just at the top of their craft. I’m picking people who are either at the top of their craft because of public perspective—you know, Beyoncé is not the singer with the most range. I’m sure she has vocal coaches, and I’m sure she's developed range over her very long career. But even in that tape, you could see like she falls flat sometimes, she’s a kid. But Jazmine Sullivan’s version is performed as a kid too, and she’s not flat at all. [Beyoncé] has so much star power, and she has so much charisma. And what you see there is charisma. She has the dance moves down. She’s fully doing Dorothy and the body language that Stephanie Mills created in the ’70s. I'm picking them based on the fact that they’re all divas at the top of their craft, and that they made the song their own.